Blue Highways (23 page)

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

“Too dangerous. That’s a hardhat area.”

“Never mind sat. I giff you a simple problem. On see floor, I put down sree sings—rifle, hoe, fishing rod and reel. Take vun and liff only by it for vun year. Alone. Vitch do you take?”

While I thought, a man wearing a Coors T-shirt came in. Everyone said, in turn, “Hello, Father.” He was the priest of Dime Box. Straddling a chair, resting his arms on the back, drinking an orange sodapop, he watched the domino game. The man

CAT

said it was his last round. The wife would wonder.

“You take so long to answer, you must be pheelosopher. I tell you sis—you von’t choose see rifle.”

“How do you know?”

“Hunters make decisions fast, like a bullet. Bang!”

“Okay, I’ll take the rod and reel.”

“Now vy is sat?”

“You didn’t say anything about ammunition, and I’d die before crops came up. I can make hooks and line and eat immediately.”

“Ahh. A man’s answer shows him.”

“Which would you take?” It was the question he was waiting for.

“Me! I take see rifle!”

A domino player said, “All you ever shot was the breeze.”

“No? No, you say? Vell, I sink about it for eighty years. And you don’t know about see var. I shot see Germans left and right. Mow sem down like hay.”

Everyone in the bar, some with slight German accents, laughed.

To me, he said, “Say sink I only can sell pants.” To the room he said, “I tell you, see muzzle vas hot like a poker. Except on veekends because sen vee trink see slivovitz.”

They all laughed again. When I left Sonny’s, the game, like a potato cell, had subdivided into two identical ones, and the little tiles fell softly on the old tables, and the man

CAT

was playing his last game. After all, the wife would wonder.

A

T

Austin, on a hill west of the Colorado River—not

the

Colorado River, but the one flowing from near the New Mexico line to the Gulf—the desert began. Desert as in dry, rocky, vast. There was nothing gradual about the change—it was sudden and clear. Within a mile or so, the bluebonnets vanished as if evaporated, the soil turned tan and granular, and squatty trees got squattier with each mile as if reluctant to reach too far from their deep, wet taproots. Highway 290, running from rimrock to rimrock of the Edwards Plateau, climbed, dropped a little, climbed again until I was twelve hundred feet higher than Dime Box. From the tops of the tableland, I could watch empty roadway reaching for miles to the scimitar of a horizon visible at every compass point. It was fine to see the curving edge of the old blue ball of a world.

Johnson City was truly a plain town. The “Lyndon B. Johnson Boyhood Home,” pleasantly plain, is here; and commercial buildings on the square were plain and homely. The best piece, the refurbished Johnson City Bank of rough-cut fieldstone, was perhaps the only bank in the country to be restored rather than bulldozed for a French provincial Tudor hacienda time-and-temperature building.

The road went directly into a sunset that could have been a J. M. W. Turner painting. Colors, texture, the horizontal composition were his. I’d never thought Turner a realist. The land, now cattle and peach country, wasn’t so rocky and dry as the great ridges I’d just crossed. West of Stonewall, I saw the last of dusk, and under a big desert night, I drove in the small coziness of my headlamps until Sonny’s beer made me stop. While I stood, an uncommon amount of noise came invisibly through the brush. Whatever it was, I felt vulnerable and tried to hurry. The moonlight wasn’t much, but what I could make out looked like a tiptoeing army helmet. I was moving backwards when I realized it was an armadillo. I stopped, it waddled on, sniffed me out at the last moment, and shifted direction without hurry.

The conquistadors named the armadillo (“little armored one”), but Texans call them “diggers” because of the animal’s penchant for scratching up larvae and worms, especially from soft soil of new graves. In spite of both the belief that armadillos feed on corpses and the animal’s susceptibility to leprosy, poor whites ate them with greens and cornbread during the Depression and called them “Hoover hogs” or “Texas turkeys” (on the Christmas table); even now, poor blacks, calling them just “dillas,” barbecue the soft meat. Ancient Mayas refused to eat them because they believed the carrion vulture did not die but rather shed wings and metamorphosed into an armadillo. But now, for a creature hardly changed from its Cenozoic ancestors, things are a little better. Texas law protects it from commercial exploitation, and that means it’s harder today to buy a lamp or purse made from an armadillo carapace.

When I got back to my rig, the critter was nosing along the highway, looking for bugs popped by cars—that’s why in the warm season so many armadillos get pressed like fossils into the soft asphalt. I honked it back to cover and drove into Fredericksburg, where I parked for the night behind the old Gillespie County Courthouse and went looking for calendars on cafe walls. The only eatery open was a big laminated place called the Hofhaus or Meisterhof or Braumeister—something like that. Having to order by number, I knew I was in for it. I chose number whatever, which proved to be three gray sausage corpses in a nest of sauerkraut that squeaked like rubber bands as I chewed and Bavarian potato salad dissolved into a post-factory slurry. I would have been better off with barbecued Hoover hog.

H

ISTORY

has a way of taking the merely curious and turning it into significance. Consider the old Nimitz Hotel in Fredericksburg, for example. Not the rebuilt Nimitz Hotel I saw, but the 1852 version.

A German immigrant, Charles H. Nimitz, knowing the value of distinctive architecture, in 1880 built on his hotel, which had long afforded some protection from the Comanches, an addition shaped like a steamboat with a prow thrusting into the bounty of Main Street. The place, with hurricane deck, pilot house, and crow’s nest, was unique, and the food toothsome. Nimitz had a good trade, once including Robert E. Lee, who slept in a spool bed here. Charles Nimitz was the grandfather of the Commander-in-Chief of the United States Pacific Fleet in the Second World War, Chester W. Nimitz. The only thing resembling a ship young Nimitz saw on the Texas plains was the steamboat hotel, and all he knew of the sea (not counting the marine fossils in the native limestone) were his grandfather’s stories about the German merchant fleet. No wonder Chester, in his first command at sea, ran his destroyer aground and got court-martialed; that was natural for a boy who grew up steering a hotel across the prairie. Nevertheless, this son of the Great American Desert later directed the victory in the largest naval war ever fought. I didn’t hear anyone in town offer a theory on the role that old Charlie Nimitz’s ship hotel played in determining the outcome of World War II, but somebody will think of it sooner or later.

For all I know, Main Street in Fredericksburg is the widest in the nation. It was so broad, I had to make a point of remembering why I was crossing to keep from forgetting by the time I reached the other side. And it was broad not for a few blocks but for two miles. Settlers from the compacted villages of the Rhine Valley laid Main out to enable ox carts to turn around in it. A shopkeeper explained: “We don’t say somebody’s dumb as an ox anymore because we’ve forgotten how dumb that is. We say a guy’s a ‘dumbass,’ although I doubt we know how dumb that is either. Be that as it may, you can’t teach an ox to back up. You can teach a horse to back up, but forget an ox. Main Street’s wide because an ox is stupid.”

People who think the past lives on in Sturbridge Village or Mystic Seaport haven’t seen Fredericksburg. Things live on here in the only way the past ever lives—by not dying. It wasn’t a town brought back from the edge of history; rather, it was just slow getting there. And most of the old ways were still comparatively unselfconscious.

Item: Otto Kolmeier & Co., a hardware store with an oiled wooden floor and shelves requiring a trolley ladder, where you could buy a cast-iron skillet, or graniteware pots to outfit a chuckwagon, or horseshoes in a half dozen sizes, a coal bucket, a coyote trap, or a brass cuspidor; the tinsmith (no sheetmetal worker this man), whistling off-key, could take his mallet and hammer out a galvanized tin trough or well cover.

Item: a flagstone sidewalk shuffled to the slickness of a marble monument.

Items: nineteenth-century buildings of scabbled and dressed limestone, sunburned to a soft yellow, erected by German settlers as soon as the Comanches left them alone long enough. The rock in building after building was so sharply cut it seemed the chink of hammer and stone chisel still vibrated in the street.

Item: a century plant, its steely spines ceaselessly dragged against a rock foundation by the wind, leaving deep incisions like a bear claw.

Item: a fieldstone building, as simple and direct as the Texas tableland, with a relief carving in white stone of an elephant above the door. Albino elephants were once symbols of hospitality, but it had been years since you could buy a drink at the White Elephant; the tavern was even long gone when the place sold Hudsons and Essexes. Now it was a German import boutique peddling Muenchen beersteins, Bavarian cuckoo clocks, and Teutonic trifles. And so the future came on in Fredericksburg, a little here, a little there.

A popular piece of sociology holds that Americans are losing confidence in the future because they are losing sight of the past. No wonder, when the good places that show the past seem so hard to find. Yet, in Fredericksburg, Texas, a few Americans were beginning to acknowledge the civilizing influence of historical continuity. They had turned the old courthouse into a library and community hall; next to its pioneer grace, the newer courthouse looked like a memorial gymnasium.

O

UTSIDE

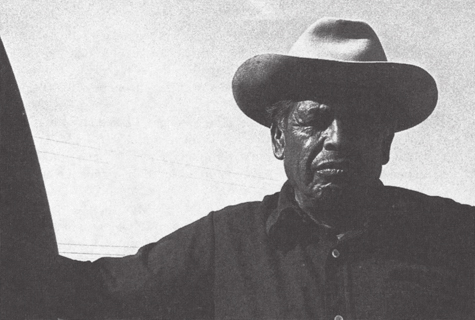

of Fredericksburg, a small brown man, unable to bend his right knee, a paper sack under his arm, limped along the road to Hedwig’s Hill. He looked directly at me, smiled, and oddly waved an upright thumb. As I passed, he waved goodbye. That’s when I realized he was hitching. I stopped.

“Gracias,”

he said in a soft voice accented in a peculiar way. “I like to go in trucks.”

I didn’t understand everything he said over the next couple of hours, but I did make out he had left Corpus Christi that morning on his way to visit a sick brother in Big Spring. He had traveled about two hundred and fifty miles on only two rides—one with a trucker, the other with a Texas Ranger, and neither noted for picking up hitchers.

“I have these thirty-five cents,” he said and showed the coins to prove it. “That’s all. The cop buy me a doughnut and coffee, and so I eat. I walk one mile before another ride. When I wait, I kill a big rotlah.”

“A big what?”

“Rotlah.” He trilled his tongue and moved his hand in a serpentine.

“A rattlesnake?”

He nodded and said yes in a high, trailing voice. “Very big rotlah.” He rolled his hands into a circle to show its thickness. “Big.”

With a rock the size of a cantaloupe, he had crushed the snake. The kill pleased him, and he talked about it for some time. It was good to destroy rattlers that came to live near men. He said cowboys used to pull the fangs from rattlesnakes and wear them around their necks to ward off fever.

“My father was a

vaquero

. Real cowboy. His hands made many things. He like best horsehair for things. Weave tail horsehair to make things. My mother she was Apache. I’m a redskin.” He smiled at that.

“What’s your name?” I thought he said “Perfidio,” but no one would name a child that. “Perfidio?” I asked, and he nodded, and I repeated and spelled it. He nodded and I shook my head. He took out his billfold, a fat thing full of slips of paper folded small, and held up his Social Security card: Porfirio Sanchez.

“Oh, Porfirio. Not Perfidio.”

“Yes.” He fished among the bits of paper for a school photograph of a girl. “Grandbaby. I have seven boys and nine girls from five wives. Now grandkids. But for marriage, I say good to be out.”

At Grit, we turned west onto route 29, a road that struck a bold, narrow course straight into the heart of the Texas desert. “Pretty good country here,” he said. Over the miles, he repeated that several times, and the way he said it—softly—sounded as if he knew, as if he’d seen many kinds of country.

The land was fenceposts and scrubby plants and not many of those. Mostly the acres were for the goats that produced the big crop here: mohair. It was the country of the San Saba River, a route of deserted stone cavalry forts built six generations ago to control the “Indian trouble.” In 1861, the post at Mason was under the direction of a lieutenant-colonel suddenly called to Washington by President Lincoln and offered field command of forces being readied for a civil war. The officer declined, and Fort Mason became his last U.S. Army duty. Robert E. Lee never forgot the isolated place.

To Sanchez I said, “Are you a cowboy?”

“I work ranches. Work many jobs. Drive trucks in Dallas. Dump trucks. But now I’m sixty-seven and don’t have no employment. I have a government check each month, but I give most money to my babies, to my grandkids.” He suddenly thrust an arm toward the desert. “Ears!” Just above the bush, a pair of long, erect ears, pinkly translucent in the afternoon light, gave away the position of a jackrabbit. “If you hunt big rabbits, look for big ears,” he said. “Mr. Rabbit hide everything but ears. Those he can’t hide unless he go deaf.”