Blue Highways (38 page)

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

He cut slow circles over the Klickitat and the rooftops of the village of Pitt eight hundred feet below, then spiraled a prolonged ascent, a thousand feet above the town. Prone under the canopy, leaning and banking, he swept out a figure eight, then wheeled down, passing a few feet above two men standing nearby. “Piece of cake until I lost my draft!” he shouted. With each turn of the helix he was lower until we were looking into the canyon at the top of the glider. Only his feet showed from beneath the red canopy puffed into a gullwing-like airfoil.

“A tremendous performance,” I said to the men.

One nodded. “The flyingest flying. No noise, no pollution.”

They drove off down the crest, with me in pursuit, into the canyon and through the village and across the Klickitat to an alfalfa field where the flier was swooping in for a hop, skip, and bounce of a landing, toppling over only at the end. It looked like the crazy tumble landing of a gooney bird. We all ran toward him. When we got there, he was still laughing.

The pilot, Alba Bartholomew, talking quickly, picked up his glider and carried it out of the field. His “kite” was a Wills Wing Cross Country with a “sail” of fifty-five-pound Dacron over an aluminum frame. The only instruments were a variometer and altimeter.

“Did you see the hawk above you, Al?” one of the men, Garland Wyatt, asked.

“Heard him. They stay on your blind side until they dive on you. Glad he wasn’t gunning for my face today.” The other man, Bob Holliston, asked about the wind. “Not bad, but I couldn’t find a warm draft blowing steady.”

Wyatt said, “That highwire walker who fell not long ago, Wallenda, he used to say the wind was the worst enemy always.”

“Enemy and friend,” Holliston said to me. “Our necessary evil. Rising currents make soaring possible. They also make it risky. We fly or die by the same force.”

“How’d you get started with this?” I asked Bartholomew.

“Saw a man on television sailing. I knew then I had to try it, so I bought a glider kit, put it together, and jumped off a hill.”

“That hill?” I pointed to the high slope he’d just swooped from pterodactyl style. Everybody laughed.

“Pitt’s a hang-three incline. Hang-four is the ultimate—like Grand Canyon,” Bartholomew said. “My first glide was off a hang-zero-point-one bump.”

“Eighty-some people died last year hang-gliding,” Wyatt said.

“How do you get yourself to make that first leap?”

Bartholomew shook his head. “Don’t know. Guess I didn’t want to waste the couple hundred dollars I’d spent on the kit. I remember being scared out of my brains. Actually, it turned out all right until I landed and mowed down about twenty yards of alfalfa. I was just ridge gliding then—running off a hill and gliding to the bottom. In the air twenty seconds on a good flight, but I took a lot of sled rides in those days, bouncing down hills. What you saw is soaring.”

Holliston, a contractor who also soared, motioned toward Pitt Hill. “Those cumulus clouds indicate thermal updrafts. Catch a cumie burning hot and you can almost corkscrew out of the atmosphere. We call it ‘skying out.’”

“What’s it feel like?”

“Hard to describe,” Bartholomew said. “Maybe free is the word, or magical. You can’t believe you’re doing it. I think it’s what a bird feels. Or Superman. But ridge gliding’s different; it’s a carnival ride. Zoom, boom!”

“You feel like a wounded goose before you take off,” Holliston said, “but once the sail fills and you’re stable, then it’s like you’ve grown wings. You can’t see the kite—all you see is ground or sky.”

“Are you scared?”

“Always edgy until you’re airborne and even a little then. You’ve got to be a little nervous or you get cocky and careless. Then it’s stuff-it time.”

“It’s a balance,” Holliston said. “We’ve got to risk a little more each time to improve and go beyond what we’ve done in the past. But if we take on too much at once, it could be the last lesson. The problem is we don’t always know when we get in over our heads. We’ve got to trust our gut reactions without giving in to them. That’s what’s hard.”

“Tell me,” I said, “what would happen if I got into your glider right now and jumped off Pitt with only a few minutes’ instruction?”

“Off Pitt?” Bartholomew shrugged. “You might live if you made yourself follow natural instincts, but I think you’d get bent up pretty good coming in. That’s nearly a thousand feet up there—about the same as jumping off the observation deck of the Empire State Building.”

“I don’t think you’d be able to climb or soar because of the turns,” Holliston said. “You’d stall in the first turn, and that would be the show. Turns take time to catch on to.”

“I learned turning from watching buzzards,” Bartholomew said. “I saw how they hesitate on the downwind leg.”

“Put it this way,” Wyatt said. “Al was the first ever off Pitt, and he’d been gliding two years before he tried it. The launch has to be almost perfect.”

“My first real soaring ended me up in a lake,” Bartholomew said, “which may have been the safest landing place considering the way I came in. My first two years I was banged up a lot: sprained neck, twisted ankles. But I haven’t been hurt the last four years. Of course, I’m not a real acrobatic type either. I

would

like to glide off Mount Adams though. Now that would be highly interesting. The problem there is severe winds. I’d have to pack my kite six thousand feet to the top, which is twelve thousand feet, and hope the wind was up, but not

too

up. If I ever think I’ve got a fifty-fifty chance of getting off, I’ll try it. Watch for it in the newspaper: dead or alive.”

“That first jump off Pitt must have been hellacious.”

“Worse than my first glide. Mountain air is rough—much rougher than California-style ocean gliding. I’d read you’ve got to have good airspeed to counteract turbulence, so I knew I had to run off the mountain, not just jump. I stood up there a long time, sort of accepting the possibility of whatever. I promised myself I’d run hard. Gliding’s not like motorcycling; for us, the more speed, the more safety. I’d read everything there was on gliding and that wasn’t much then. I hoped I’d remember it when I needed it. I saw people watching down on the highway, and I knew I’d have a good audience if I stuffed it. Might as well die in a spectacular crash.”

“We hate audiences,” Holliston said. “Damned applause from beautiful girls.”

“Anyway, I took my run and jumped. My heart got a good rest up there when it stopped beating. My whole body said, ‘How could you do this to us?’ “

“The technology was crude then. The glide ratio of early kites was about three to one—three feet horizontal for every foot vertical

if

you knew what you were doing. Those kites were flying rocks.”

“This glider,” Bartholomew said, “has a glide ratio of ten to one. Eight years ago it was something for anyone to stay up an hour. Now time aloft depends more on weather and your biceps than on the machine.”

“How high can you go?”

“No one knows yet. One pilot did ten thousand feet, but if you don’t get a good thermal, you sink about a hundred feet a minute. With a long burner, who can say? I’ve ridden a hot column up two thousand feet above The Dalles.”

“Two thousand feet hanging onto a piece of Dacron? No parachute?”

“After a hundred feet, it’s all the same if you lose it. Except for a new model, parachutes are too heavy and restricting. I wouldn’t buy one anyway because I’d be tempted to try it, and I’ve never parachuted. Lose my kite too if I jumped.”

“Hang-gliders aren’t as flimsy as they look,” Holliston said. “They’re stressed for six G’s whereas a Boeing Seven Forty-seven is stressed for three. Of course, there’s some relativity in there.”

Wyatt went home, and Bartholomew rolled up the glider and lashed the twenty-foot bundle to his pickup. He said, “Come on back with us.”

Holliston rolled his eyes. “Trophy time.”

Alba Bartholomew lived in Klickitat, a company town of seven hundred in the narrow vale of the Klickitat River. His little frame house was like the others on the street except for the windsock blowing on the roof. He worked at the St. Regis sawmill, where he ran a stacker. It wasn’t the most interesting of jobs. The mill got much of its timber from the Yakima Reservation twelve miles north. St. Regis was the reason for Klickitat, and when the Yakima’s big ponderosa were gone, people feared the company would pull out and Klickitat would go the way of Liberty Bond.

Bartholomew’s wife grilled hamburgers, and we sat talking and drinking Olympia in the front yard. At first the topics were technical—wing stress, nose altitudes, load factors—but after we’d eaten and had some more beer, the conversation took a different cast. Maybe it was the Tumwater in the beer.

Bartholomew drew a sketch of an airfoil. “Today, hang-gliders are variations of one a man named Francis Rogallo made about 1949, although most of the changes came in the early seventies, after NASA decided not to use them to bring down space capsules. A new technology for a new sport.”

“The Wright brothers started out with hang-gliders, but the concept’s older,” Holliston said. “Leonardo da Vinci sketched something that looks like early gliders. Five hundred years before the idea became a working thing.”

“When I first got into it,” Bartholomew said, “you almost had to buy a new kite every year just to keep up with the aerodynamic changes. New models were much better and safer.” He got out a pamphlet on hang-gliding. “Man who wrote this is paralyzed now from a crash.” He offered that as if he’d told me the man was left-handed.

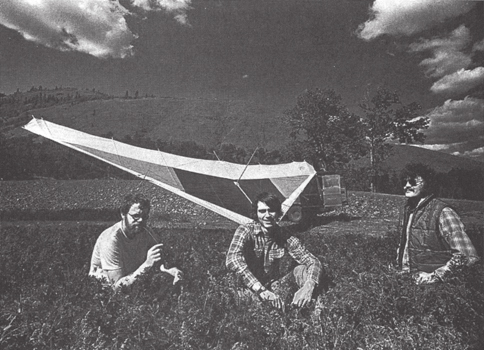

14. Bob Holliston, Al Bartholomew, and Garland Wyatt near Pitt, Washington

“If you stay at it long enough, something’s bound to go wrong,” I said.

“If I flip a coin ninety-nine times and it comes up heads every time, the odds are still fifty-fifty when I flip the hundredth time. Besides, each flight I learn something, and learning makes for safety.”

“That’s probably true,” Holliston said, “but I think the real answer to why we fly is because it’s addictive. It’s a buzz to put everything on the line. Whenever we go up, we’re subconsciously asking the most important question in the world—asking it real loud—‘Is this the day I die?’”

“You’re really pumped up when you come back down; it’s great to be up, but afterwards the earth feels so good and you think how you’ve gotten away with it one more time. Still, it took me a year of flying before I could relax enough to call soaring a pleasure. Even water’s a more natural place for a man than the sky.”

“You’re not a bird just because you fly like one,” Holliston said, “but it seems like you are. There’s no compartment around you so you feel and hear the wind just like the birds. Man’s oldest dream.”

“You hear the wind when you’re in it?”

“You’d better hear it, otherwise you’re into a stall and it’s time for the last thrill. You gauge safety, which is airspeed, by the sound of the wind.”

“It’s hard to explain how good it feels to be totally alone up there, where everything depends absolutely on yourself. Until you’ve felt the freedom of that, and how your senses come alive, you really can’t understand soaring.”

“Freedom’s a misleading word, though, because we’re only free as long as we balance gravity and thermals. It’s like both sky and earth want us. They’re both pulling. We get to fly as long as we keep things balanced, and that’s where the sensation is—when we’re hanging between up and down.”

“Sometimes it seems like—I don’t know,” Bartholomew said abstractedly. “Sometimes I just get to thinking I can stay up forever if I can only keep the balance. You can get so outside yourself, you start believing you belong in the sky. Like you were born up there. That’s when it’s most dangerous—and the best.”

“You sound like Icarus.”

“Of course, you never can maintain the balance,” Holliston said. “Something always comes along and changes things. Mr. Down gets you every time.”

I

FOLLOWED

the road, the road followed the Klickitat, and the river followed the rocky valley down to the Columbia. At The Dalles another dam—this one wedged between high walls of basalt. Before the rapids here disappeared, Indians caught salmon for a couple of thousand years by spearing them in midair as the fish exploded leaps up the falls; Klickitats smoked the salmon over coals, pulverized the dried flesh, and either packed it in wicker baskets lined with fishskins for use during the winter or they tied the cooked salmon in bundles for trading to other tribes. The fish kept for months and some even ended up with Indians living east of the Rockies.

The cascades provided such a rich fishing site that Lewis and Clark called The Dalles “the great mart of all this country.” Natives found a new source of income in the falls when white traders came with boats to be portaged. One fur trader complained, as did many early travelers, that the Indians were friendly but “habitual thieves”; yet he paid fifty braves only a quid of tobacco each to carry his heavy boats a mile upriver.

East of the dam, the land looked as though someone had drawn a north-south line forbidding green life: west, patches of forest; east, a desert of hills growing only shrubs and dry grasses. The wet coastal country was gone. A little before sunset, in the last long stretch of light, I saw on a great rounded hill hundreds of feet above the river a strange huddle of upright rocks. It looked like Stonehenge. When I got closer, I saw that it was Stonehenge—in perfect repair. I turned off the highway and went down to the bottomland peach groves, where a track up the hill led to the stones. They stood a hundred yards south of several collapsed buildings.