Blue Highways (64 page)

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

At the east window she showed me Point Comfort Island, an uninhabited place heavy with small pines and only a hundred yards across the narrow inlet from the Ewell pier. “Our people won’t live on it. Too far from things. Besides, it’s an island.”

“What’s Smith?”

“Land surrounded by water. Like Australia.”

We went downstairs. Miz Alice pulled out a big bony thing with a vague, skull-like appearance. “Oysterman drudged it from the bay. Brought up a whole passel of bones. In nineteen fifty-nine my students packed two orange crates of the bones off to the Smithsonian. Here’s what they said.” She handed me a letter thanking her and identifying the bones as the spine of an extinct species of whale. “Whale vertebra! Look closely.” She stood the massive bone on end. “Eyes here, mouth, nose. Don’t you see a monster skull?”

“I lean toward a vertebra.”

“Ye gods and little fishes! Life is stranger than that!” She looked out the front door. “What do you think of our right, tight isle?”

“I like it.”

“So you say. I’ll give you a hiking tour tomorrow over to Rogue’s Point.”

Miz Alice phoned a friend, the wife of a tonger, to secure a room for me. I walked down to the harbor and ate dinner at Ruke’s Grocery, an old shingled place with a broken cash register drawer standing full and open. Beach flotsam hung about the room: embossed bottles turned iridescent with age, antique running lights, a worn dip net, broken crockery, an eroded block and tackle. The watermen drank coffee topped with melted cheese and lounged about in the sweetness of fresh produce and frying crab cakes. Five boys, all looking alike although only two were brothers, pitched pennies over the floor that rose and dropped like a wooden sea.

I rambled around the village in the cool night, then, at eight, went to the home of Mrs. Bernice Guy, who showed me my room, a small thing with a sagging bed and oval photographs of women from the time of Chester A. Arthur.

She said, “Our island’s a nice place, but people visit once and not again. One time, though, in your bed Henry Cabot Lodge slept.”

The next morning, Miz Alice and I tramped the dusty road over the guts, through the tall waterbush, toward Rogue’s Point. She named the trees, few as they were: loblolly pine, gum, pin oak, red cedar, poplar, even a pomegranate and fig. The larger trees were ones that could survive when the taproot grew long enough to reach salt water. She pointed out the sights too: a house where six boys and six girls were reared to adulthood, a heron pecking and swallowing.

As we walked, a speeding, unmufflered car forced us to the edge. “Wherever Hoss is going, he’ll soon be there,” she said. “When I came to the island, we all had working feet. Courting was nothing but strolling unless you wanted to go sing in church. We traipsed the lanes at night. Cows would snort at you from shadows and scare the lantern out of your hand. Cattle slept anywhere they pleased because there’s not enough high ground for pasturage, but we never had to cut lawns. Footmen we were then.”

The car whipped past the other way. “Swoosh, yourself,” she said. “Here we can never be more than a mile or so from any place we can reach by feet, and yet our people aren’t walkers any longer. They keep two cars—one on the island, another at Crisfield. As for kids, they know one thing to do—drive from Ewell to Rhodes Point and back. Up and down, slow or fast, it matters not. They know every inch of the way but can’t distinguish an egret from a crane.”

The salt marsh was a place of beauty, yet along much of the road lay junk: mattresses, rusted barrels, appliances, a drive shaft, tires, a sofa. At one gut full of cans, Miz Alice said, “I’ve yet to see a bean can sprout. Won’t be long for that gut now.” She shook her head. “The grave’s for people when they’ve seen enough, but how can you see enough when you’re twenty? I read in the

Sun

that kids feel disconnected. How can that be? Connections lying over the land like stardust. They live in the Land of Nod.”

We came to a high piling of rusting automobiles, where a teenager was stripping wheels from a smoldering pickup. “He’s found a drowned man with a pocketful of money,” she said. “We’re a dead end here when it comes to merchandise. There aren’t any repair shops on the island, so whatever gets shipped out here stays. We’re at the end of the assembly line, and there it is. Not enough space to hide from our junk. You’d think living beside trash we’d do something about it, but all we do is get used to it. We think it’s the way of things.”

“Is the cause poverty?”

“We have no poor except those that choose to be—those that would be poor as gar broth anywhere, the ones who work only so they can quit. No, the cause is education. Not enough of the proper kind at the right time.”

She told about the organization of the island: no mayor, no jail, no local taxes, no water bill unless you counted the annual twenty dollars for maintenance of the artesian wells. The water, delicious and cold, has its source in the Blue Ridge Mountains. “A natural underground ‘pipeline’ from Virginia to us. I think it was our good water that finally got us to build a sewage system to replace septic tanks. In the nick of time.”

We came to Rhodes Point, a single street of watery yards hung with fishing nets and stacked with chicken-wire crab pots. Everywhere lay oyster shells, their pearly interiors gleaming like bits of a broken necklace. We weaved in and out of the yards, and Miz Alice commented on more sights: a birdbath supported by three plastic sea horses (“Properly belongs on a wedding cake”), a peculiar house with a chimney above the front door (“Do you enter through the fireplace?”), and, overlooking the bay, an old house with a new picture window on the second floor (“Wouldn’t catch me up there in a nor’wester unless you chloroformed me”). When we came to a front yard with a stone obelisk in memory of Job A. Evans, who drowned in Tangier Sound, I asked why it wasn’t in the cemetery.

“It’s not rightly a grave. Never found the man. Chesapeake keeps her dead. But the islanders do sometimes dig graves in their yards because land is at such a premium.”

Yet, next to the old Methodist church, a big wooden building not at all of a size commensurate with the tiny fishing village, was a burial ground of watermen’s tombstones carved with bugeyes and skipjacks.

Miz Alice stopped at a fresh grave. “Fifteen years old. Sitting in his car one night, made a little sound, and fell over dead with dope. Went to his funeral. The young find their drugs, even out here.”

At one empty home, a large telescope house built by Captain Hoffman, we looked in the broken windows. “Never did get my curiosity cured,” she said. “Some people sit around and wait for the world to poke them. Right here in this old curiosity shop of a world, they say, ‘Poke me, world.’ Well, you have to keep the challenges coming on. Make them up if necessary.”

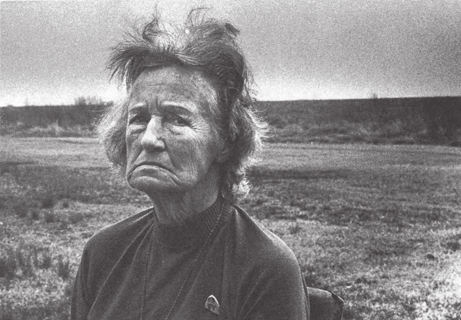

23. Alice Venable Middleton on Smith Island, Maryland

At the end of the street, which was also the end of dry ground, the island became a tangle of water and weed, neither solid nor liquid but a treacherous in-between running most of the way to Tylerton. On the bay side of Rhodes Point stood crab houses and pounds with shedding floats where peelers were held until they molted. “Once the crab peels, you have to pull him out directly or the water will start him to hardening again. That is, if another doesn’t eat him first, soft morsel that he is for a few hours.”

Tied up at the pier was the

Island Belle,

an old skinny wooden boat of quaint lines. Miz Alice said, “Listen to this sentence: the

Island Belle

—she’s a gas boat—she changed our social pattern. Some people wouldn’t agree, but it’s the truth. She made her first crossing the month I arrived sixty-three years ago. She’s never been underwater, and that’s something here.”

“How was it she changed the island?”

“Before the

Belle,

people got to the Eastern Shore once a year—at Christmas. She brought passage. Regular comings and goings. We got outside and the outside got in. She ended our isolation. Carried mail and medicine, the sick and dying. Brought news, food, gas, firewood. Even ideas, I deem. There aren’t many places in the country that can point to one thing and say; ‘Right there,

that’s

the thing which changed us.

That’s

what made us the way we are now.’”

“It’s hard to imagine.”

“Imagine what America would look like without the car, then you’ll know what this island would be like without the

Belle

. Now, of course, teenagers ride to high school in Crisfield on the bus boat. I’m not even sure we’re an island anymore, unless you spell it capital I-hyphen-l-a-n-d. Catch the difference?”

She looked down a narrow cove. “Land sakes! Tide’s coming in. Let’s hoof it back. I’ll be getting tired around the knees soon.”

The walk to Ewell was quieter and slower. Miz Alice asked how I came to be in Maryland. I told her and used Whitman’s phrase about “gathering the minds of men.”

She said, “When olden-day travelers went about, they might carry something called an

Album Amicorum

to gather the signatures and sentiments of learned men they visited along the way. Is that what you’re doing?”

“I’ve thought of the trek more as just the bear going over the mountain to see what he could see.”

At “Scud In” I stopped to get my duffel so I could catch the afternoon boat to Crisfield. “I have a question for you,” I said. “Tell me what’s the hardest thing about living on a small, marshy island in Chesapeake Bay.”

“I know that and it didn’t take sixty-three years to figure it out. Here it is, wrapped up like a parcel. Listen to my sentence. Having the gumption to live different

and

the sense to let everybody else live different. That’s the hardest thing, hands down.”

T

HE

telescope house may not be indigenous to the Eastern Shore, but there were more of them here than anywhere else. The name derived from the linking of three houses, each successively larger, so that the two smallest ones look as if they could slide, telescope fashion, into the largest house. The design came about for economic reasons: a young family built a small two-room home; as the family and income grew, they added a “wing” of usually four rooms and later another addition of six rooms. Along the back roads north of Crisfield were many of them, most with standing-seam metal roofs.

On a peninsula between the Choptank and Tred Avon rivers, I came to Oxford, a seventeenth-century village of brick sidewalks and nineteenth-century houses. Only a few small streets branched off the main trunk, Robert Morris Street, a way of aesthetically cohesive homes and yards fenced by the Oxford picket—a slat with a design at the top that looks like an ace of clubs with a hole shot in it. The pickets were popular, even though painting the holes could take all spring.

At the bottom of Morris Street, across from the Tred Avon ferry slip, sat the Robert Morris Inn, the 1710 portion of which, built by a shipwright, was once the home of Robert Morris—Senior and Junior—a family of fortune and misfortune. The father died when wadding from a cannon fired in his honor struck him in the arm. The son, one of the wealthiest men in eighteenth-century America and a financier of the Revolution, was sentenced to three years in a Philadelphia debtor’s prison after a spell of reverses, one of which was the failure of the new government to repay his loan to the Continental Army.

Like some of the homes on Morris Street, the inn had fallen into disrepair by the 1940s after Oxford, a commercial port of entry the equal to Annapolis in the early years, lost its trade and, later, most of its fishing fleet. But, in the last decade or so, people from Baltimore, Washington, and Philadelphia began recognizing the calm and beauty of the little harbor town, and the new bay bridges across the Chesapeake near Annapolis made the Eastern Shore easily accessible. Newcomers moved in and started renovating the old homes. Now, in the boatyards rode motor-sailers and sloops and cabin cruisers; in the inn, mail-order-catalog yachtsmen and wives leafed through picture books of Eastern Shore hunting decoys and referred to the old houses as “architectural statements.” That was the new old Oxford. But between the inn and the harbor lay an old old Oxford: a tight cluster of worn houses of the blacks who had spent their lives here.

I took the Tred Avon ferry, at three centuries the oldest operating cable-free ferry in the United States, to Bellevue and drove out the double-fingered peninsula toward Tilghman Island. On the way was St. Michaels, “the town that fooled the British” by inventing the blackout. During the War of 1812, word reached the citizens that a night bombardment was imminent. Residents doused all lights except candles in second-story windows and lanterns they hung in treetops. British gunners misread the lights, miscalculated trajectories, and overshot the town. The trick preserved numerous colonial buildings, including one home where a stray cannonball fell through the roof and bounced down the stairway past the startled lady of the house.

By dusk, I was on Tilghman Island, an island only by virtue of a streamlet called Knapps Narrows. I parked near the wharf where much of the last sail-powered fishing fleet in America tied up. Against the clouding sky, I could make out the tall masts and long bowsprits of the skipjacks, ships that hoist twelve hundred feet of sail to pull port and starboard dredges over the oyster rocks. Some people believed the skipjacks were the last of an era while others held they were, once again, the future.