Blue Highways (7 page)

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

The crossing became a grim misadventure, and I wasn’t prepared for it. I tried to think of other things. Helen Keller, who never drove the Clinch Mountains, said life is a daring adventure or it is nothing. Adventure—an advent. But no coming without a going. Death and rebirth. Antithetical notions lying next to each other, as on a globe the three-hundred-sixtieth degree does to the first. Past and future.

The road reached the summit, started dropping fast, then a blessed

END CONSTRUCTION

, the pavement reappeared, and the mist turned to rain that at last washed the windshield clean. Goodbye, mountain.

I came to a long sprawling of businesses in metal buildings: auto upholstery recovered, brakes relined, transmissions rebuilt, radiators reconditioned, mufflers replaced. Nothing for renewing a man. Across the Holston River, wide and black as the Styx, and into the besooted factory city of Morristown, where, they say, the smoke runs up to the sky. Sorely beset by the blue devils, I wandered looking a long time for a quiet corner to spend the night. Finally, I gave up and pulled in a bank parking lot. “They can run me out or in. To hell with it.” With the curse, I went to bed.

I

MIGHT

as well admit that the next morning in smoky Morristown I was asking myself what in damnation I thought

he

was doing. One week on the road—a week of clouds, rain, cold. And now it was snowing. Thirty-four degrees inside the Ghost, ice covering the windshield, my left shoulder aching from the knot I’d slept in. “It is waking that kills us,” Sir Thomas Browne said three centuries ago. Without desire, acting only on will, I emerged from the chrysalis of my sleeping bag and poured a basin of cold water. I thought to wash myself to life.

Outside, the spiritless people were clenched like cold fists. A pall of snow lay on the city, and black starlings huddled around the ashy chimney tops. Clearing the windows, I wondered why I had ever come away to this place and began thinking about turning back. Could I?

I cranked the sluggish engine. Four lanes of easy interstate from Morristown to Missouri. One day. The engine fired, sputtered, and caught. I listened as I did every morning. Smooth but for the knocking waterpump. I moved out. A red light at U.S. 11 East. Home was a left turn, right was who knows. “A man becomes what he does,” Madison Wheeler had said. I took who knows.

Snow plastered the highway markers, so I watched the compass and guessed. The road to Jonesboro via Whitesburg and Chuckey wound about hillocks of snowy trees and houses puffing chimney smoke. It was like riding through a Currier and Ives monochrome. Meadowlarks, fluffing full, crouching on fenceposts, held their song for the sun. A crooked sign:

ICE COLD WATERMELON.

The highway once was a stage route of inns, but the buildings that had withstood the Civil War weren’t surviving the economics of this century. East of Bulls Gap, surveyors’ pennants snapped in the wind. Another blue road about to join the times. Taverns and creaky Gen. Mdse. stores (two gas pumps and a mongrel on the porch) were going for frontage-road minisupers. The rill running back and forth under the highway, of course, would have to be straightened to conform to the angles and gradients of the engineers.

Highway as analog: social engineers draw blueprints to straighten treacherous and inefficient switchbacks of men with old, curvy notions; taboo engineers lay out federally approved culverts to drain the overflow of passions; mind engineers bulldoze ups and downs to make men levelheaded. Whitman: “O public road, you express me better than I can express myself.”

T

HE

fourteenth state in the Union, the first formed after the original thirteen, was Franklin and its capital Jonesboro. The state had a governor, legislature, courts, and militia. In 1784, after North Carolina ceded to the federal government its land in the west, thereby leaving the area without an administrative body, citizens held a constitutional convention to form a sovereign state. But history is a fickle thing, and now Jonesboro, two centuries old, is only the seat of Washington County, which also was once something else—the entire state of Tennessee. It’s all for the best. Chattanooga, Franklin, just doesn’t come off the tongue right.

Main Street in Jonesboro, solid with step-gabled antebellum buildings, ran into a dell to parallel a stream; houses and steeples rose from encircling hills. After breakfast, I walked snowy Main to the Chester Inn, a wooden building with an arched double gallery, where Andrew Jackson almost got tarred and feathered, for what I don’t know. Charles Dickens spent the night here as did Andrew Johnson, James Polk, and Martin Van Buren (whose autobiography never mentions his wife).

At the inn, now the library, I read about ears in Jonesboro’s history. A sheriff once branded a horsethief’s cheeks with H and T before nailing him by the ears to a post; later, to set him free, he cut them off. Then there was pioneer Russell Bean, who returned from a two-year business trip to find his wife nursing an infant; to make known the identity of his true sons, he bit off the baby’s ears.

On the way out of town, I saw a billboard advertising a bank:

WHEN YOU’RE BETTER YOU GET BIGGER.

Pleasant little Jonesboro, a size Martin Van Buren would recognize, gave the lie to that. Snow still fell, but the flakes seemed to be dropping one at a time. Route 321 was closed for construction; a fifty-mile detour followed the Little Doe River, a stream of clear water cascades, up through fields of hand-piled haycocks. Then the highway rose to cross Iron Mountain and brought me down in North Carolina. The hazy Blue Ridge Mountains lay at my back, the snow stopped, and I drove among gentle hills. A thousand miles into the journey.

East by Southeast

W

HAT

happened next came about because of an obese child eating a Hi-Ho cracker in the back of an overloaded stationwagon. She gave me a baleful stare. As I passed, the driver, an obese woman eating a Hi-Ho, gave me a baleful stare, Ah, genetics! Oh, blood!

Blood. It came to me that I had been generally retracing the migration of my white-blooded clan from North Carolina to Missouri, the clan of a Lancashireman who settled in the Piedmont in the eighteenth century. As a boy, again and again, I had looked at a blurred, sepia photograph of a leaning tombstone deep in the Carolina hills. I had vowed to find the old immigrant miller’s grave one day.

Highway 421 became I-85 and whipped me around Winston-Salem and Greensboro. For a few miles I suffered the tyranny of the freeway and watched rear bumpers and truck mudflaps. As soon as I could, I took state 54 to Chapel Hill, a town of trees, where I hoped to come up with a lead on the miller in the university library. All I knew was this: William Trogdon (1715–1783) supplied sundry items to the Carolina militia for several years during the Revolutionary War; finally, Tories led by David Fanning found him watering his horse on Sandy Creek not far from his gristmill and shot him. His sons buried him where he fell. Fanning terrorized the Piedmont through a standard method of shooting any man, white or red, who aided the patriots; and he was known to burn a rebel’s home, even with a wife and children inside. Faster than King George, Colonel Fanning turned Carolinians to the cause.

After I’d given up in the library, by pure chance as if an omen, in a bookshop I came across an 1856 map showing a settlement named Sandy Creek east of Asheboro. That night I calculated the odds of finding in the woods a grave nearly two hundred years old. They were lousy.

The next morning I headed back toward Asheboro, past the roads to Snow Camp and Silk Hope, over the Haw River, into pine and deciduous hills of red soil, into Randolph County, past crumbling stone milldams, through fields of winter wheat. Ramseur, a nineteenth-century cotton-mill village secluded in the valley of the Deep River, was the first town in the county I came to. I had to begin somewhere. Hoping for a second clue, I stopped at the library to ask about Sandy Creek. Another long shot. “Of course,” the librarian said. “Sandy Creek’s at Franklinville. Couple miles west. Flows into Deep River by the spinning mill. Town’s just sort of hanging on now. You should talk to Madge in the dry goods across the street. She knows county history better than a turtle knows his shell.”

Madge Kivett was out of town, but a clerk took me back across the street to the Water Commissioner, Kermit Pell, who owned the grocery and knew something of local history. In Pell’s store you still weighed vegetable seed on a brass counterbalance with little knobbed weights; the butcher’s block was so worn in the center you could pour a bucket of water over it and only a pint would run off.

Pell, a graying, abdominous man with Groucho Marx eyebrows, chewed gum and continually took off and put on his spectacles. Sitting in a dugout of ledgers and receipt books, he couldn’t reach the phone so I had to hand it to him the six times it rang. Between rings, it took an hour to get this: the miller’s isolated grave had been covered by a new hundred-twenty-seven-acre raw water reservoir (the town bought the grave twice when two men claimed ownership—buying was cheaper than court). The old tombstone, broken up by vandals digging in the grave to look for relics, had been moved to the museum; the commissioners transferred a few token spades of dirt and put up a bronze and concrete marker a few feet from the original gravesite. The Asheboro

Courier-Tribune,

in an article dated two years earlier to the day, told of the imperiled grave setting off a hurried archaeological survey to turn up both colonial history and artifacts from a thousand years of Indian camps. The site, the clipping said, “although known to historians, is deep in the wilds of the creek.”

“I’ve got to see it,” I said.

“It’s a hell of a walk in. You better know what you’re doing before you go into that woods. I mean, it’s way back in there.”

“Can you give me directions?”

“Only one person I know of could show you—if he would. Noel Jones over in Franklinville might lead you in. Lived along the creek all his life. He’s getting on now, but you can ask for him at the mill.”

T

HICK

muddy water in the ancient millrace of Randolph Mills at Franklinville curled in slow menace like a fat water moccasin waiting for something to come to it. The mill ran on electricity now, and the race was a dead end—what went in didn’t come out. Inside, spoked flywheels tall as men spun, rumbling the wavy wooden floors and plankways, but no one was around. It seemed a ghost mill turned by Deep River. I knocked on the crooked pine doors; I tapped on a clouded window and pressed close to see in. On the other side, an old misshapen face looked back and made me jump.

“Looking for Noel Jones!” I shouted.

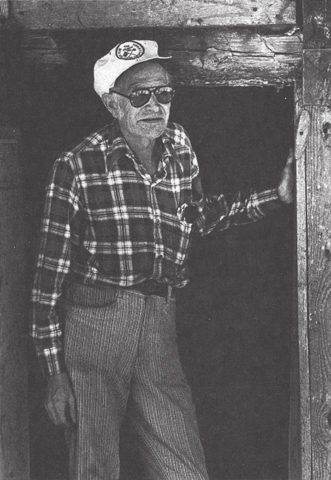

The face vanished and reappeared at a doorway. It said, “Gone home. First street over,” and disappeared again. I took the street, asked at a house, and found Jones at the end of the block.

“I know the place you’re alookin’ for,” he said, “but I’m not up to goin’ back in there just now. Got a molar agivin’ me a deal of misery.”

“I understand, but maybe you could describe the way.”

He took off his cap and ran his hand over his head. “It’s possible to walk in. Not so far you cain’t. But directions gonna be hard. Sorry I cain’t take you.” He put his cap back on. “Tell you what. Get in my truck and I’ll show you where to start. It’ll keep my mind off this molar. One thing though, you got some work in front of you, son. And not aknowin’ the way, well, that’s a worry of its own.”

In the warm afternoon, we followed a dirt road until it turned into a grassy trail so narrow the brush screeched against the windows. At a small clearing, he stopped. “This is my old family property,” he said. “Just down the hill you can see Sandy Crick. The old mill of yours musta been right along there. Let me show you somethin’ else.”

We walked over to a cabin with only the back wall of logs still standing. Hanging to it was a warped kitchen cabinet lined with layers of newspaper. “July of ’thirty-six on this paper,” Jones said. “Used to stick it up to keep wind out of the cracks. Pitiful. But look at the price of shoes.”

He pulled a broken coffee cup from the cabinet, scowled, and put it back. “When I was a boy, an old fieldhand lived in this house. He was adyin’ of pneumonia one night my daddy took me by, and I watched through the window. Man was out of his mind with fever, and he thrashed in bed. He thought he was aplowin’ with his mule, John. ‘Come on over, John! Pick it up there, John!’ Whole night he and that mule plowed, we heard. Dead by mornin’. My daddy said he worked himself to death that night. Said if he coulda put the plow down, he mighta rested enough to live. Those days, it was hard livin’ and no easier dyin’. Took thirteen months a year to grow ’bacca.”

We went on through a hump of woods into another clearing where stood several small tobacco sheds with roofs falling in and an old smokehouse.