Bluestockings (17 page)

Authors: Jane Robinson

Rooms in the hostel for King’s College, London, were lavishly and precisely furnished in the early 1920s with the following: 1 couch-bed and bedding, 3 blankets, 2 green rugs, 1 oblong table, 1 chest, 1 mirror, 1 green wardrobe curtain, 2 green window curtains, 1 basket chair, 2 wooden chairs, 1 basket, 1 bookcase, 1 cream net blind, and 1 blue-and-white bedspread.

5

By contrast, when girls arrived at Durham in the 1930s, they were advised to bring all their tea things with them (china and cutlery), two pairs of sheets, pillowcases, table napkins, a napkin ring (not silver), face and bath towels, an eiderdown, rug, and easy chair.

6

They were liable to share a bedroom. They slept on settees which turned into beds at night, with ‘a well-used 2'' flock mattress over chicken-wire’, dingy with coal dust, and they used one of only two bathrooms available in college. The bathroom floors were of bare concrete with duckboard mats, and they were

so

cold.

7

Gwendolen Freeman was grateful to find her rooms at Girton rather better than she had expected. They were on the ground floor, distinguished by a stern, blank-eyed bust of Gladstone stationed outside the door. Gwendolen felt she owed a great deal to Gladstone. Girton’s corridors were so long, so numerous and uniform, that she relied on the sight of him, standing sentry, to guide her home.

In her first letter home, she proudly drew a plan of her rooms (most students at Girton, as at Royal Holloway, had two). Her study was plain, carpeted in blue, with ‘pale nondescript walls’ and its own little fireplace. The bedroom was more cheery, with flowery wallpaper, a red mat and eiderdown, a large Victorian washstand complete with its old-fashioned equipment, and a curtained-off area for hanging up Gwendolen’s (two) dresses, and stashing the woolly

underwear. The windows, strangely, had no curtains; only bars on the outside to prevent the recurrence of an incident involving a ‘tramp’ who, according to Gwendolen the ingénue, ‘once tried to get in thinking it was the work-house’.

8

Gwendolen’s first job, the evening she arrived, was to unpack and personalize her suite. Up went the picture-wire and watercolours she had brought from home; she scattered her favourite cushions, arranged the dressing-table set her mother had presented her with, and ceremonially placed a sturdy new mantelpiece clock above her fireplace. That clock, she noted as it belted out the hour, ‘was going to be very useful to both me and neighbouring students’.

9

In Manchester’s Ashburne Hall, you were allowed a chair each which, in the early days, you were advised to carry about with you wherever you went and were likely to want to sit down. A girl in one of the hostels run by the Society of Home Students at Oxford brought her own chair: it came from her Uncle Jim’s cabin on HMS

King George V

, and was, like him, a venerable relic of the Battle of Jutland.

10

University Hall in Liverpool was humbly furnished with a hotch-potch of donations by local well-wishers. In the 1908–9 session alone, it was given some china for the dining room, various magazines, fruit trees for planting, some concert tickets, cushions, a croquet set, garden seeds, a sewing machine, a mowing machine, novels for the library, and some curtain material – all received with delight.

11

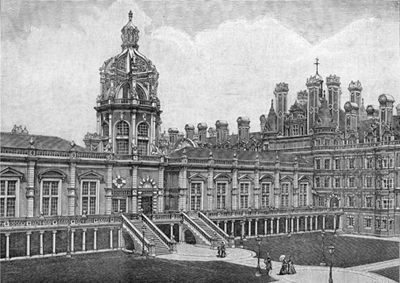

An imposing corner of Royal Holloway College in about 1886.

Royal Holloway College in Surrey reclined complacently at the opposite end of the spectrum. Founded in 1883 by a local businessman, in memory of his wife, it carried a £200,000 endowment – equivalent in today’s money to about £9.5 million – and accommodated 250 young women in wings of magnificent bedrooms with separate studies. Its opulence persisted well into the 1930s, when Audrey Orr remembers dressing for dinner each evening and gathering at the chime of the dinner gong (sounded by Pine, the butler) to process through the library and museum into Hall, each student with another – or a member of the tutorial staff – on her arm.

12

Freda Taylor had the unusual experience of witnessing her university, Hull, coming into being:

[I]n 1926 I saw the first pile driven into the marshy ground bordering Cottingham Road. On October 11, 1928 I was one of the twenty or so first students waiting for admission on the steps of one of the two unfinished red brick buildings then standing on the same site. There were… eight women at Thwaite Hall (four of them called Kathleen…) under the watchful eye of a female Cerberus, Miss Murray… We were to discover there were almost as many staff as students.

13

Settling in here, with the first ever cohort, was easy. The students set their own precedents. Conforming to the customs and strictures of long-established and insular institutions elsewhere could be extremely difficult, especially if, like Beryl Harding, you felt you did not fit. Her family, described as ‘lower middle class’ and mostly ‘clerks and bank officials’, had no interest in academia, nor any knowledge of what life as a student was like. Beryl arrived at Oxford in 1929, propelled there by forceful schoolteachers, without confidence, money, or much hope of happiness.

She disliked the culture of discipline at college intensely. She felt the maids (appropriately known as scouts) were encouraged to spy on students and inform on misbehaviour.

The rules laid down that a student, meeting a young man, had to have an approved companion. The Principal had to give her permission and kept a book outside her door for these requests to be entered. We filled one in, now and then, ‘to keep her happy,’ as we said. Otherwise the rules were ignored. I still think an institution whose rules are held in contempt, is not a healthy one.

14

Beryl’s most sickening memory of college discipline involved a friend, Elizabeth, who had been brought up with the four boys of a neighbouring family. Elizabeth had known these lads all her life: they were as close as brothers. One of them, John, was studying theology at Keble College. When his mother visited Oxford one weekend, Elizabeth – eager to show her gratitude and affection – asked her Principal for permission to invite John and his mother to tea in her college room. The mother was welcome, allowed the Principal, but definitely not John. Men were safe enough in company, Elizabeth was told, but John ‘might find his way back again later’.

15

*

Navigating the choppy waters of college regulation was a perilous business for freshers. Who could anticipate, for example, some of the abstruse house rules at Royal Holloway, issued during the early decades of the twentieth century? No hair to be thrown out of windows; permission to be sought for biking on Sundays; chapel doors to be shut on the fourth strike of the bell, and all students not inside by then to be punished; smoking only allowed in the afternoons in the remotest part of the grounds, and only after 4.00 p.m. in public corridors; no tennis on Sundays; stockings to be worn at all times and in all weather, even on the river; tennis shorts (in the late 1930s) to be no shorter than one inch off the ground when kneeling, and cut in pleats to hang like a skirt; and so on. Transgression, at some point, was almost inevitable, and became a matter of honour to a feisty few.

The system still in use today (in an expanded form) of college ‘godparents’ was designed to support bewildered students. New girls were allotted individual seniors to look after them for the first few days, and give them guidance. Occasionally this worked well, but too often hapless ingénues were abandoned after a single meeting, or even a hastily scribbled note (‘Dear Alison, I hope you are not too frightened…’).

16

Nothing mitigated the strangeness or intimidating nature of one’s fellow freshers, who tended to be categorized into types. An undergraduate at Somerville in 1935 decided they were all either As (with more sex appeal than she), Bs (a fair fight), or Cs (the rest):

Group A girls had a comely and bespoken look. They tended to wear suede waistcoats and gold earclips pointing upwards like ivy leaves. Their conversation was of champagne breakfasts and how ideas were more rewarding than people.

17

*

At Durham, and elsewhere, there were popularly only two categories: ‘the studious sister or the dashing damsel’;

18

in other words, clever girls who patently worked too hard to get their beauty sleep, and ‘fast’ ones who were stupid. You called girls you liked ‘chaps’, and those you didn’t, ‘females’.

Meeting chaps and females en masse was even more terrifying than one by one, and mealtimes were particularly alarming. Vera Brittain’s first dinner at Somerville was almost unbearable. Everyone (but she) seemed to be screeching instead of talking, and the noise shrilled around the lofty hall like a siren. Everyone (but she) looked dowdy, dressed in joyless, long-sleeved frocks. The food was dull, the crockery depressing, and the thought of this night after night was unendurable.

Actually, the immature Vera was not intimidated by her peers – they disgusted her:

It required all my ambition, and all my touching belief that I was a natural democrat filled with an overwhelming love of humanity, to persuade me that I had never really felt the snobbish revulsion against rough-and-readiness which my specialised upbringing had made inevitable.

19

She was lonely, feeling physically detached and socially isolated. There were plenty of girls who perceived university to be dangerously elitist, educating them – as one put it – ‘out of [their] real class in society’, before spitting them out as misfits and strangers. Others, like Vera, considered themselves too self-contained, too sophisticated (in the purest sense of the word), to relax. Shyness works both ways.

Traditionally, of course, everyone you encounter on your first day at university seems much more brainy, worldly-wise, and self-assured than you. Sometimes they really are: several

students remember Gertrude Bell, at Lady Margaret Hall, as the most brilliant woman of her generation. She went on to excel as a traveller, writer, and diplomat; at Oxford she was remarkable as a vibrantly beautiful and intelligent student who achieved a first in modern history after only two years’ study, at the age of barely twenty. Apparently she had corrected one of her own examiners during finals, but with such grace and self-assurance that nobody minded.

It is also a truism that once you have recovered your confidence, you recognize that here is an exhilarating opportunity to make friends unencumbered by the preferences of your family or the confines of your school. To some this was disconcerting: ‘I find it bewildering deciding if I like people by myself. I have been used to them labelled.’

20

Others found it faintly distasteful, like Vera Brittain. She had chosen Oxford in 1914 because there, she hoped she might ‘begin to live and to find at least one human creature among my own sex whose spirit can have intercourse with mine’. There was no such creature in her cohort. In the preternaturally academic atmosphere at college, she considered herself unique, ‘one of the “lions” – perhaps the “lion” of my year’. She realized such intellectual superiority was likely to seclude her from her peers, but that was not important. ‘I might be hated by all my year at the end of a term,’ she admitted, ‘but I do not think I shall be, as people here are not jealous & resentful as they are at school.’

21

That last comment was somewhat naive.

Unlike Vera, most girls relaxed into the novelty of directing their own relationships, and remember endless evenings fuelled by cocoa, cakes, and helpless giggles in the company of girls from all over the world. Academic work was a duty; being silly in company with other silly people was an unalloyed delight.

Mary Applebey went to St Anne’s in the days when it was

the Society of Home Students, just before the Second World War. She was billeted in a hostel with eleven other girls, all of whom became part of the fabric of her future. She lived with one of them for fifty years. The survivors still keep in touch, and their children, and children’s children, treat each other as family. Yet this was a completely random group of people. Mary herself had an academic upbringing: her mother had been at Somerville, and married her chemistry tutor. Of the others, a few were from clergy families; one was a rich builder’s daughter from Birmingham; one was an overseas student from Hong Kong; one a bright, rebellious girl from Wales; another followed a family tradition into Oxford. Two took pass (two-year) degrees, the rest took honours.

22

They explored Oxford together, comrades in academia, and their shared experience proved stronger than their disparate histories.