Born to Be Brad (10 page)

Authors: Brad Goreski

Christmas 1996. I’m wearing Club Monaco pants that are way too big for me. I’ve got a belt on, yet it doesn’t look like it’s even cinching anything. And then there are the platform boots and my famous Caesar haircut. All in all, this is a big fashion don’t!

“Remember that audition I told you about?”

“No,” he said.

“Well, I got it! And it’s filming today!”

Of course there was no audition. There was no acting job. But I’d been out all night and I couldn’t bring myself to get up from bed. I was folding chinos at the Gap during the day, but at night I was hanging out at the drag clubs in Toronto. And I developed definite opinions about which queens were talented and which ones were phoning it in. I had no time for the queens who didn’t bother to learn the lyrics, who stood onstage mouthing “

apples, pears, and peaches

” in time with the music. Frankly, as a theater student I was offended. By the way, everything I know about drag—from tucking, to shading, to contouring the bridge of the nose—I learned from RuPaul’s book

Lettin It All Hang Out,

which I read in my first year of college when I had mono.

Life that summer was a big party. But when I returned to school in the fall, the party didn’t stop.

I quit working at the Gap and found a job waiting tables at Five Doors North, an Italian restaurant on Yonge Street. The restaurant was so cool there wasn’t even a sign outside. You had to know about it to find it, which I loved. The food there was delicious—inexpensive, small plates for people to share—and I think the owners kept it reasonably priced so people would drink more wine, which they did. It was a party atmosphere at the restaurant, for the customers and the staff, too. It was around this time that Whitney Houston was in the first throes of her abuse, and we had a wall in the kitchen where we hung up newspaper clippings of her awesome exploits. People would come in to see the “Whitney Wall of Shame.” I was working with a bunch of lost souls. But they were lost souls I loved being around. Every night felt like a performance. And sometimes it was. I’d get up on the bar and lip-synch to Jennifer Holliday, usually while the restaurant was still packed with customers. One night I grabbed a super-straight guy’s motorcycle helmet and did runway down the bar. I told everyone I was in the Alexander McQueen show.

Sashay!

Chantez

!

WHAT YOU CAN LEARN FROM DRAG QUEENS

Drag queens live in a universe of heightened glamour—the hair is big, the lashes are long, and the sequins are extra sparkly. They offer us an insight into their ideas of femininity, sexuality, and humor. It’s about creating a character, dressing up, living your fantasy in front of others. Drag queens own who they are, and more important, they are fashion trailblazers and fantastic creative minds. A constant source of inspiration!

“I was working with a bunch of lost souls. But they were lost souls I loved being around. Every night there felt like a performance.”

And for the first time in my life, I was making good money. I used to walk around this great department store, Holt Renfrew—Toronto’s answer to Barneys—and lust over the Prada shoes and the Versace. Now I could almost afford these things. I bought my first pair of Prada shoes, these square-toe slip-on loafers, while I was still in school. I bought a charcoal-gray Versace T-shirt with black cap sleeves and a textured nylon material running down the back. In retrospect, it was hideous, and I wore it all the time. I bought a black Alexander McQueen knit polo with this viscose material weaved through it. I still remember the tag, which was black with red lettering. It felt luxurious. We wore street clothing to work, and I was into tight tops and Versace jeans and Miu Miu shoes. We always turned it out for Saturday nights, when the regular customers came in. Our look was definitely late-nineties Toronto gay—Euro and super-tight.

I was out all the time, dancing after work, doing drugs with friends and coworkers. But wasn’t everyone? This was college. This is what being twenty years old in a big city for the first time is all about. At least that’s what I thought. I didn’t yet recognize that I had a problem. Because an addict doesn’t see it coming. That’s why people stay using. That’s why people die. It’s because they can’t see the signs.

Still, I knew enough to hide it all from Trish Lahde, a classmate from theater school. Trish was from Sault Ste. Marie in Northern Ontario, a place even farther removed than Port Perry. The winters at theater school were long, the days even longer, and we often emerged from the bowels of the refrigeration and upholstery classrooms in the dark. But we had each other. With Trish, I was clean. With Trish I was Bradley Goreski from Port Perry. We watched teen comedies from the eighties together and danced to Madonna. One night, I showed her videos from elementary school. She started to cry.

Despite my best efforts, the abuse was not helping my performance in school. I was exhausted all the time. Luckily this was theater school and the curriculum was full of exercises where one was asked to lie down on the ground and act like animals. There were days where we pretended to be in “zones of silence.” One day, I actually fell asleep on the floor, and the teacher called me out on it, really ripping into me. I swiftly jumped in, explaining, “I have chronic fatigue syndrome. I can’t really help it. It’s not my fault.” I don’t know where the lie came from. I guess I was better at improvisation than I thought. And the teacher was convinced. Not only did he believe my excuse, but in my year-end progress report, he praised me for my perseverance. “Despite his chronic fatigue syndrome,” he wrote, “Brad is still able to succeed.”

“I thought I was holding it together. Addicts always do. But others knew.”

But six months later, I couldn’t really hide the addiction anymore. I was working at the restaurant, staying out all night, and then trying to go to class. I couldn’t see how far out of balance I was. I thought I was holding it together. Addicts always do. But others knew. My parents made the hour-long drive into Toronto every Sunday night to take me grocery shopping. Back then, I just thought they wanted to spend time with me. Later I realized that wasn’t it at all. They took me grocery shopping because they didn’t want to give me the cash. Because they knew what I’d spend it on.

“And I learned a valuable lesson that year: You can’t let someone take your dream away from you.”

Soon, the school administration asked me to leave. I pushed back and was put on probation instead. It felt like a terrible rejection. Theater school can be a test of self-esteem; you open old wounds in class to find a character, and to have my weaknesses thrown back at me felt like too much. I dug in my heels. I refused to be a failure. I was stubborn, like a Leo. School was something I wanted. And I learned a valuable lesson that year: You can’t let someone take your dream away from you. My teachers rejected me, but they couldn’t deny my success in a play called

Dancock’s Dance

by Guy Vanderhaeghe. I portrayed a schizophrenic man-child in an asylum, a kid who believes he is the king of Germany and is sexually abused by the other patients, and there wasn’t a dry eye in the theater.

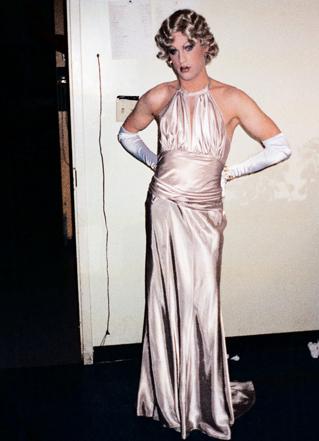

As a theater student at George Brown College in Toronto, I dressed as Marlene Dietrich for a cabaret show, singing “Mean to Me” live. My teachers believed this undercut my talent and that I’d embarrassed myself.

Sometimes it was all too much. One afternoon early in the third year of drama school, I stood outside one of our classrooms, crying hysterically into my hands, collapsing onto Trish’s shoulder. She was my touchstone. But as much as I tried to hide my drug use from her, she knew it was more than recreational.

“I need help,” I said. “I need help. I can’t do this anymore.”

Trish was holding me. She was the nonjudgmental voice of reason. “Whatever you need,” she said. “Do you want to leave? Do you need to go home?”

I went to exactly one Cocaine Anonymous meeting, but it didn’t take. I wasn’t ready. I couldn’t yet see that everything was connected. I hadn’t hit rock bottom. I still had a roof over my head. I was still holding down a job. I was still functioning. A few weeks later Trish asked me about the meeting, but I dismissed her, telling her I felt nothing. And when she tried to ask me again a few weeks later, I blew her off. I turned a deaf ear to the voice of reason.

The only voice I heard now belonged to a man. A gorgeous man named Nick.

G

raduation was approaching, and I was out one night with a drag queen named Tiger Lily, a Pocahontas look-alike with curly black hair (her own). We were way up above the dance floor looking down at a sea of shirtless men. And there was Nick, dressed in jeans and nothing else, his eyes closed, moving to the music.

“If I could date anyone in Toronto,” I told Tiger Lily, “it would be him.”

A few months later, in March of 1999, she and I were at the Snowflake Ball—or some other party where cardboard snowflakes hang from the ceiling—and there was Nick again. Except this time he was walking directly toward me. I was twenty-one years old. He was forty-three and told me he had two children. It wasn’t the kind of news one expects to hear at a club where grown men are sucking on Ring Pops and wearing angel wings. But there we were.

It felt like a scene out of a movie. I was this skinny kid with a bad Caesar haircut and semi-bad clothes, hanging out with low-rent drag queens and people who weren’t all that cool. I was always on the outside looking in. I still felt like that kid on

Electric Circus,

the one who was asked to dance in the window hidden behind a sheet. And then Nick showed up. And he was so handsome—like a cross between George Clooney and the guy from

General Hospital,

the one who plays Sonny. And he was talking to me! And I could feel so many pairs of eyes on me, wondering who I was, wondering why this man who everyone wanted was suddenly interested in me. I felt like an ugly duckling finally becoming a swan. I felt a sense of self-worth for the first time. And that night, we closed the place down.

“It felt like a scene out of a movie.”

Four months later I moved into Nick’s house, not quite in the suburbs, but not quite in the city either. I was domestic. And I was trying to be clean. While it sounds like a bad made-for-Logo movie, I have to say, the relationship started out well enough. Actually, it was kind of like that movie

Stepmom,

right down to the scene where Nick’s daughter and I danced in her room doing her hair. I gave her style tips, too. I took her out to lunch.

And ours was this thrilling Gay-December relationship. He was the first man to take me on a proper date. We went to restaurants I’d passed by in the gay area of Toronto and only dreamed of going into. Places I used to walk by and think, I can’t even afford to buy a drink there. But suddenly I was inside having an appetizer

and

dinner. I was used to eating the eight-dollar bowl of stir-fry from a place called Spring Rolls, and now I was one of the pretty people.

“Ours was this thrilling Gay-December relationship.”

It was very romantic. I was still working at the restaurant, and I’d get off the late shift and go meet Nick and his friends somewhere to dance. He was friends with

the

group in Toronto. The muscle boys. The cool go-go dancers. The cool lesbian couples. When I’d go out with them, I was so skinny I looked like a Chihuahua in a room full of pit bulls. I was this wispy thing with my little fashions. I’d go into Nick’s closet and style him for the night. He didn’t care about fashion but he loved Madonna and he loved me and it was heaven. I’d been obsessed with Gianni Versace, and a few years earlier when his boyfriend murdered him, I’d had a meltdown for a couple of days. And so, when Nick and I went to Florida for New Year’s Eve 1999 to celebrate the millennium, my first stop was the Versace mansion to pay my respects. That night, Nick and I dressed in matching silver pants (made out of plastic!) with tight white T-shirts and black shoes and silver bandannas around our necks. Did I regret this look? No way. Who regrets wearing anything in Miami? I was fake-tanned and ready to go—there’s no other way to survive the Toronto winter. (I do, however, regret the time in college when I fell asleep in the tanning bed and the manager didn’t wake me up. I was in there for fifteen minutes and couldn’t participate in my classes for two days because I was so badly charred and couldn’t lay down on my back. You could actually see the imprint of where the lightbulbs had been. It was not cute.)

Life with Nick was a whirlwind: I was dancing to Deborah Cox remixes and Whitney Houston was making a comeback and I knew all the lyrics and it was always five in the morning and we were shutting down some club and going to the twenty-four-hour deli to get ice cream and Gummi bears. We’d stay awake until the sun came up and we’d talk and laugh and then the next weekend we’d do it all again. Nick came into my life at a time when my parents were divorcing. My mother had called me over Thanksgiving to ask if I was coming home. I was, I said, and she answered, “Good. It’ll be the last Thanksgiving we spend together as a family.” In that time, Nick was so gentle. He’d been through a divorce himself and he knew the effect it could have on someone.