Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (23 page)

CHAPTER 9

THE WEDDING

“ If [your enemies] give any annoyance, laugh at them. The man who smiles on his adversary gets the best of the fight. [I] recommend the same remedy and believe it would be equally effective if applied to the men now trying to disunite and mislead the Democracy.”

—Tweed, in a pre-election speech to democrats in the Fifth Ward

(today’s “Tribeca” neighborhood), November 5, 1870.

B

OSS Tweed looked the proudest of fathers and the best of hosts on May 31, 1871, dressed in his black evening formal suit, diamond flashing on his chest, as he stood in church to give his eldest daughter, Mary Amelia, away in marriage to 25-year-old Arthur Ambrose Maginnis of New Orleans. Tweed made the wedding magnificent in every way. Carriages clogged the streets around Trinity Chapel on West 25th Street as the hour approached. Inside the jammed church, well-wishers rose to their feet as the wedding party began its procession, the ladies “aglow with rich silks and satins and flashing with diamonds” with a “confusion of white arms and shoulders, elegant laces and valuable jewelry.”1 Richard Tweed, the bride’s brother, led the wedding march, walking arm in arm with Maggie Maginnis, the groom’s sister, followed by Frank Tweed with Josephine Tweed. Mary Jane Tweed, the bride’s mother, marched with her new son-in-law wearing a gown of “salmon-colored silk, elegantly trimmed with deep

point aiguille

lace,” a reporter noted.

Tweed escorted his daughter down the aisle as the organ rose in Mendelssohn’s Wedding March played by popular pianist E.A. Gilbert. She wore “white corded silk, décolleté, with demi-sleeves, and immense court train” with orange blossoms at her waist and, on her bosom, “a brooch of immense diamonds, and long pendants, set with three large solitaire diamonds, sparkled in her ears.”

2

Reverend Joseph Price, who twenty-seven years earlier had conducted Tweed’s own marriage to Mary Jane Skaden at the old church on Chrystie Street, presided now again for Tweed’s daughter.

Tweed and his family had blossomed into New York celebrities that spring. A sailing sloop, the “

General Tweed”

named for oldest son William Jr., raced the fastest yachts in New York harbor, and a racehorse, the “

Richard M. Tweed

,” named for his next-eldest son, won contests at the Fleetwood Park Track. William Jr. had grown into a skinny, side-whiskered, good-natured 25-year-old who enjoyed his growing fame. Beyond being an assistant district attorney, a commissioner of street openings, and a state militia general on Governor Hoffman’s staff, he’d recently been appointed receiver of the Commonwealth Fire Insurance Company, a major legal case covered in the newspapers.

3

Showing political flair even his father would envy, William Jr. broke tradition that summer by making himself chief sponsor of the Excelsior Guards, the first all-black militia regiment to march in a city July Fourth parade since the ugly 1863 draft riots and welcomed them to loud cheers outside the Blossom Club on Fifth Avenue.

4

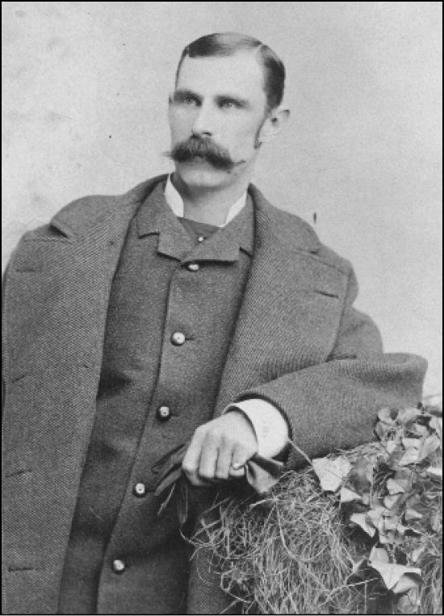

William Tweed, Jr.

Tweed’s son Richard, too, had begun making his mark. As the 23-year-old manager of the Metropolitan Hotel—which his father rented for $90,000 per year from retail king A.T. Stewart—he’d launched a costly renovation of the hotel’s 400 guestrooms with new furniture, new carpets, new lace curtains, all paid for by the Boss. A grand opening banquet promised to be a social highlight of the summer.

Tweed himself gloried as the city’s grand benefactor, Santa Claus with a diamond pin. In the weeks before the wedding, he’d showered New York with largesse. In April, as Public Works commissioner, he’d awarded contracts for $800,000 in city improvements: paving roads from Water to Hudson to Hoboken Streets, installing sewers on Second, Third, and Tenth Avenues, and one throughout Harlem costing $433,000 alone, and grading land to lay streets in the unsettled regions north of Central Park—all steps to transform clogged, chaotic Manhattan into a livable city. The

New-York Times

cried foul on the street contracts, but few people believed the charges.

5

Merchants largely applauded: “from Boulevards and cross-streets are laid out and improved in the highest style of Tammany Art—opened, regulated, curbed, guttered and sewered, gas and water mains laid, with miles and miles of Telford-McAdam pavement, streets and avenues brilliantly lighted by fancy lamp-posts,” cited the

Real Estate Record and Builder’s Guide

.

6

Tweed that year also laid plans for a grand new engineering feat—the viaduct railroad, which would provide intra-city transit by running trains on two forty-foot high masonry bridges that would be built for $40 million each and run the entire length of Manhattan—a plan greater even than the Brooklyn Bridge and bolder than the fledgling schemes for elevated subways.

Oakey Hall, in his annual mayor’s report issued that June, proposed spending $20 million over the coming three years to “improve the water-front, repave streets, finish boulevards, supply [repair] defects in sewage and drainage, and widen, cut, and extend streets”—extravagance to some, but progress to most.

7

Rather than pay higher taxes for all this, the city simply sold more bonds, mostly to investors in Europe. “It is quite generally understood … that the Rothschilds are to advance a sufficient sum of money through [August] Belmont as their agent in this country to purchase all the indebtedness of New York City,” chided a rare critic.

8

It seemed like a great free ride, especially for the banks and brokerage houses making huge commissions on the bond sales. Tweed economics—borrow, spend, and keep some for yourself—made sense to New Yorkers. Even the poor benefited. In May, Tweed sat with his fellow Apportionment Board members Peter Sweeny, Dick Connolly, and the mayor to accept applications for charitable donations, money Tweed had won from the Albany legislature. The Five Points Mission, the Ladies Union Relief Association, the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, the Association for Deaf Mutes, the Saint Joseph’s Asylum, and a dozen others all came forward.

9

Few New Yorkers noticed the cracks forming in the system. But overseas, foreign investors, particularly European bankers who held the city and county bonds, had seen the recent attacks in the

New-York Times

and begun to worry about their investments. In April, the respected Berlin journal

Zeitschrift fur Kapital und Reute

had sent shudders through German fiscal circles by arguing that only the reputations of bond underwriters Rothschild and Discounts Gesellschaft made it still trust the financial soundness of New York securities.

10

Credit continued to flow, but cautiously.

Tweed didn’t mind letting his family tug him around to buy yachts, horses, or expensive weddings. “[O]rdinarily very determined and courageous, [Tweed] is a great coward on the water, and disliked yachting parties,” despite his owning two large boats himself, a newspaper said of him. Tweed is “very susceptible to the influence of women and can be wheeled by them into doing many things he would not otherwise undertake,” it went on, though “the women in Tweed’s case are his relatives and not improper characters.”

11

Two years earlier, when Tweed had married off his second-eldest daughter, Elizabeth, to Arthur Maginnis’ younger brother John Henry, the city barely took notice. This time, in 1871, at his height of fame, every newspaper sent a reporter to the wedding and spectators thronged the streets around Trinity Chapel to gawk at celebrities.

After the church service, Tweed led the guests back to his Fifth Avenue home for the season’s most elegant reception. A blue and white awning covered the sidewalk in front of the entrance as carriages arrived. Inside, the bride, groom, and parents greeted friends under bouquets of japonicas, roses, and white tuberoses; flowers and more flowers, “all from my own place at Greenwich,” Tweed bragged to a

New York Sun

reporter. Flowers from his greenhouses decorated the parlors, stairways, and arches, forming scarlet letters M. [for Maginnis] and T. [for Tweed] in one room and a huge harp of green and white with baskets of roses in another. A band played promenades and dances. “A magnificent supper was also spread and wine flowed with profusion,” a newsman wrote.

12

Delmonico’s restaurant served dinner—a meal so elegant it took its kitchen two days to prepare. Guests included a dazzling roster of city officials.

As the night wore on and dancers swooned, guests began gravitating toward an upstairs room to gawk at a stunning sight: the wedding gifts set out on a display table, silver, gold, diamonds, pearls, and plate settings filling an entire chamber, including forty silver sets, one with over 240 pieces. One reporter described “a cross of eleven diamonds, pea size” from a state senator, “diamonds as big as filberts” from a judge, “a pin of sixty diamonds, representing a sickle and sheaves of wheat” from a city contractor, “bronzes, thread lace, Cashmere shawls, rare pictures, everything that could be conceived of which is rich and costly.”

13

Another reporter, this one from the

New York Herald

, pegged the gifts’ total value at “over $700,000,” causing even this normally friendly newspaper to gasp: “Seven hundred thousand dollars! What a testimony of the loyalty, the royalty, and the abounding East Indian resources of Tammany Hall!”

14

Descriptions would dominate newspaper reports for days. The

New-York Times

jumped on the extravagance for a new round of attacks, deriding the bride’s trousseau as “the most costly design” and her dress “the richest ever produced, and fit for a Princess” at $4,000. The wedding, coming on top of the hubbub over the statue, Tweed’s shirt-front diamond pin, and his ostentatious charities, all pounded in day after day by the

New-York Times

and in Thomas Nast’s cartoons, began to change the city’s image in Tweed to a shallow caricature—rich, flagrant, and arrogant.

Of his close friends, only one had declined an invitation to the wedding: Oakey Hall, the mayor and his wife apparently sent no present and gave no excuse for staying away.

F

OOTNOTE

More than the others, Hall seemed to sense a rising unease in the city, though blinded by his own glibness. Addressing a meeting that summer when Chinese exclusion became the topic, he quipped, “on such a hot night as this, it is well to consider the coolie question.”

15

-------------------------

Jimmy O’Brien too stayed away from the Tweed wedding. By June, he still had not decided what to do with the explosive transcripts of city accounts he’d had copied by his friend Copeland. Months had passed since Tweed and Sweeny had rejected his payoff demands. Lacking any better idea, he waited. “These figures were my protection, they were the ammunition which I depended on to make my defense against their attack,” he explained.

16

He found himself isolated. Most of his fellow Young Democrat insurgents had made peace with Tweed, some selling their friendship for healthy amounts: Michael Norton and Henry Genet, two anti-Tweed legislators in early 1870, had since received checks totaling $10,000 and $30,000, respectively, from Tweed.

17

“There wasn’t one of them who hadn’t been bought,” O’Brien commiserated.

18

Perhaps he still hoped to force Tweed’s friends to relent on his $350,000 claim for sheriff’s expenses—a lot of money to hold his attention—but personal friction made that increasingly unlikely. “O’Brien hated Sweeny, and Sweeny detested O’Brien,” journalist Charles Wingate reported, “while Sweeny was vindictive and malignant, O’Brien was hot-tempered and revengeful.”

19

O’Brien went out of his way to aggravate the wound. He continued to visit Tweed and taunted the older man with blackmail over the secret ledgers, pushing the Boss to lend him money; he took checks of $6,000 each in November 1870 and May 1871 and signed a thirty-day promissory note for a $12,000 loan on May 1. But when the note came due in early June, he refused to pay—essentially picking Tweed’s pocket for $12,000.

21

He claims he saw Tweed a final time that spring in Tweed’s office and that Tweed had begged him to relent: “You can have anything you want. I will have your father nominated for Sheriff, and I will see that he is elected. I will make you a rich man for the rest of your life.” When O’Brien asked Tweed how he’d pay for it, he recalled Tweed’s blurting “What the ___ do you care… as long as you get the money.”

22