Bradbury, Ray - SSC 07

Read Bradbury, Ray - SSC 07 Online

Authors: Twice Twenty-two (v2.1)

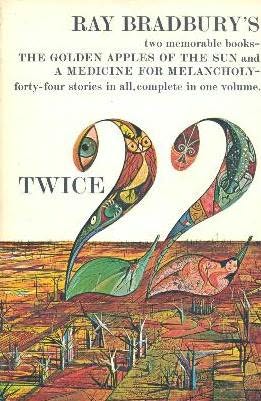

Twice Twenty-two

Ray Bradbury

Contents

5

THE FRUIT AT THE BOTTOM OF THE BOWL

9

THE GOLDEN KITE, THE SILVER WIND

12

THE BIG BLACK AND WHITE GAME

14

THE GREAT WIDE WORLD OVER THERE

22

THE GOLDEN APPLES OF THE SUN

8

THE TOWN WHERE NO ONE GOT OFF

12

DARK THEY WERE, AND GOLDEN-EYED

18

THE GREAT COLLISION OF MONDAY LAST

And this one, with love, is for

Neva

,

daughter

of Glinda

the Good Witch of the South

. . .And pluck till time and times are done The

silver apples of the moon, The golden apples of the sun.

W. B. YEATS

Out there in the cold water, far from land, we

waited every night for the coming of the fog, and it came, and we oiled the

brass machinery and lit the fog light up in the stone tower. Feellng like two

birds in the gray sky, McDunn and I sent the light touching out, red, then

white, then red again, to eye the lonely ships. And if they did not see our

light, then there was always our Voice, the great deep cry of our Fog Horn

shuddering through the rags of mist to startle the gulls away like decks of

scattered cards and make the waves turn high and foam.

"It's a lonely life, but you're used to

it now, aren't you?" asked McDunn.

"Yes," I said. "You're a good

talker, thank the Lord."

"Well, it's your turn on land

tomorrow," he said, smiling, "to dance the ladies and drink

gin."

"What do you think, McDunn, when I leave

you out here alone?"

"On the mysteries of the sea."

McDunn lit his pipe. It was a quarter past seven of a cold November evening,

the heat on, the light switching its tail in two hundred directions, the Fog

Horn bumbling in the high throat of the tower. There wasn't a town for a

hundred miles down the coast, just a road which came lonely through dead

country to the sea, with few cars on it, a stretch of two miles of cold water

out to our rock, and rare few ships.

"The mysteries of the sea," said

McDunn thoughtfully. "You know, the ocean's the biggest damned snowflake

ever? It rolls and swells a thousand shapes and colors, no two alike. Strange.

One night, years ago, I was here alone, when all of the fish of the sea

surfaced out there. Something made them swim in and He in the bay, sort of

trembling and staring up at the tower light going red, white, red, white across

them so I could see their funny eyes. I turned cold. They were like a big

peacock's tail, moving out there until

midnight

.

Then, without so much as a sound, they slipped

away,

the million of them was gone. I kind of think maybe, in some sort of way, they

came all those miles to worship.

Strange.

But think

how the tower must look to them, standing seventy feet above the water, the

God-light flashing out from it, and the tower declaring itself with a monster

voice. They never came back, those fish, but don't you think for a while they

thought they were in the Presence?"

I shivered. I looked out at the long gray lawn

of the sea stretching away into nothing and nowhere.

"Oh, the sea's full." McDunn puffed

his pipe nervously, blinking. He had been nervous all day and hadn't said why.

"For all our engines and so-called submarines, it'll be ten thousand

centuries before we set foot on the real bottom of the sunken lands, in the

fairy kingdoms there, and know real terror. Think of it, it's still the year

300,000 Before Christ down under there. While we've paraded around with

trumpets, lopping off each other's countries and heads, they have been living

beneath the sea twelve miles deep and cold in a time as old as the beard of a

comet."

"Yes, it's an old world."

"Come on. I got something special I been

saving up to tell you."

We ascended the eighty steps, talking and

taking our time. At the top, McDunn switched off the room fights so there'd be no

reflection in the plate glass. The great eye of the light was humming, turning

easily in its oiled socket. The Fog Horn was blowing steadily, once every

fifteen seconds.

"Sounds like an animal, don't it?"

McDunn nodded to himself. "A big lonely animal crying in the night.

Sitting here on the edge of ten billion years calling out to the Deeps, I'm

here, I'm here, I'm here. And the Deeps do answer, yes, they do. You been here

now for three months, Johnny, so I better prepare you. About this time of year,"

he said, studying the murk and fog, "something comes to visit the

lighthouse."

"The swarms of fish like you said?"

"No, this is something else. I've put off

telling you because you might think I'm daft. But tonight's the latest I can

put it off, for if my calendar's marked right from last year, tonight's the

night it comes. I won't go into detail, you'll have to see it yourself. Just

sit down there. If you want, tomorrow you can pack your duffel and take the

motorboat in to land and get your car parked there at the dinghy pier on the

cape and drive on back to some little inland town and keep your lights burning

nights, I won't question or blame you. It's happened three years now, and this

is the only time anyone's been here with me to verify it. You wait and

watch."

Half an hour passed with only a few whispers

between us. When we grew tired waiting, McDunn began describing some of his

ideas to me. He had some theories about the Fog Horn itself.

"One day many years ago a man walked

along and stood in the sound of the ocean on a cold sunless shore and said, 'We

need a voice to call across the water, to warn ships; I'U make one. I'll make a

voice like all of time and all of the fog that ever was; I'll make a voice that

is like an empty bed beside you all night long, and like an empty house when

you open the door, and like trees in autumn with no leaves. A sound like the

birds flying south, crying, and a sound like November wind and the sea on the

hard, cold shore. I'll make a sound that's so alone that no one can miss it,

that whoever hears it will weep in their souls, and hearths will seem warmer,

and being inside will seem better to all who hear it in the distant towns. I'll

make me a sound and an apparatus and they'll call it a Fog Horn and whoever

hears it will know the sadness of eternity and the briefness of life.'"

The Fog Horn blew.

"I made up that story," said McDunn

quietly, "to try to explain why this thing keeps coming back to the

lighthouse every year. The Fog Horn calls it, I think, and it comes. . .

."

"But—" I said.

"Sssst!" said McDunn.

"There!" He nodded out to the Deeps.

Something was swimming toward the lighthouse

tower.

It was a cold night, as I have said; the high

tower was cold, the light coming and going, and the Fog Horn calling and

calling through the raveling mist. You couldn't see far and you couldn't see

plain, but there was the deep sea moving on its way about the night earth, flat

and quiet, the color of gray mud, and here were the two of us alone in the high

tower, and there, far out at first, was a ripple, followed by a wave, a rising,

a bubble, a bit of froth. And then, from the surface of the cold sea came a

head, a large head, dark-colored, with immense eyes, and then a neck. And

then—not a body—but more neck and more! The head rose a full forty feet above

the water on a slender and beautiful dark neck. Only then did the body, like a

little island of black coral and shells and crayfish, drip up from the

subterranean. There was a flicker of tail. In all, from head to tip of tail, I

estimated the monster at ninety or a hundred feet.

I don't know what I said. I said something.

"Steady, boy, steady," whispered

McDunn.

"It's impossible!" I said.

"No, Johnny, we're impossible. It's like

it always was ten million years ago. It hasn't changed. It's us and the land

that've changed, become impossible. Us!"

It swam slowly and with a great dark majesty

out in the icy waters, far away. The fog came and went about it, momentarily

erasing its shape. One of the monster eyes caught and held and flashed back our

immense light, red, white, red, white, like a disk

held high and sending a message in primeval

code. It was as silent as the fog through which it swam.

"It's a dinosaur of some sort!" I

crouched down, holding to the stair rail.

“Yes, one of the tribe."

"But they died out!"

"No, only hid away in the Deeps. Deep,

deep down in the deepest Deeps. Isn't that a word now, Johnny, a real word, it

says so much: the Deeps. There's all the coldness and darkness and deepness in

the world in a word like that."

'What'll we do?"

“Do? We got our job, we can't leave. Besides,

we're safer here than in any boat trying to get to land. That thing's as big as

a destroyer and almost as swift."

"But here, why does it come here?"

The next moment I had my answer.

The Fog Horn blew.

And the monster answered.

A cry came across a million years of water and

mist. A cry so anguished and alone that it shuddered in my head and my body. The

monster cried out at the tower. The Fog Horn blew. The monster roared again.

The Fog Horn blew. The monster opened its great toothed mouth and the sound

that came from it was the sound of the Fog Horn itself. Lonely and vast and far

away. The sound of isolation, a viewless sea, a cold night, apartness. That was

the sound.

"Now," whispered McDunn, "do

you know why it comes here?"

I nodded.

"All year long, Johnny, that poor monster

there lying far out, a thousand miles at sea, and twenty miles deep maybe,

biding its time, perhaps it's a million years old, this one creature. Think of

it, waiting a million years; could you wait that long? Maybe it's the last of

its kind. I sort of think that's true. Anyway, here come men on land and build

this lighthouse, five years ago. And set up their Fog Horn and sound it and

sound it out toward the place where you bury yourself in sleep and sea memories

of a world where there were thousands like yourself, but now you're alone, all

alone in a world not made for you, a world where you have to hide.

"But the sound of the Fog Horn comes and

goes, comes and goes, and you stay from the muddy bottom of the Deeps, and your

eyes open like the lenses of two-foot cameras and you move, slow, slow, for you

have the ocean sea on your shoulders, heavy. But that Fog Horn comes through a

thousand miles of water, faint and familiar, and the furnace in your belly

stokes up, and you begin to rise, slow, slow. You feed yourself on great slakes

of cod and minnow, on rivers of jellyfish, and you rise slow through the autumn

months, through September when the fogs started, through October with more fog

and the horn still calUng you on, and then, late in November, after

pressurizing yourself day by day, a few feet higher every hour, you are near

the surface and still alive. You've got to go slow; if you surfaced all at once

you'd explode. So it takes you all of three months to surface, and then a

number of days to swim through the cold waters to the lighthouse. And there you

are, out there, in the night, Johnny, the biggest damn monster in creation. And

here's the lighthouse calling to you, with a long neck like your neck sticking

way up out of the water, and a body hke your body, and, most important of all,

a voice like your voice. Do you understand now, Johnny, do you

understand?"

The Fog Horn blew.

The monster answered.

I saw it all, I knew it all—the million years

of waiting alone, for someone to come back who never came back. The million

years of isolation at the bottom of the sea, the insanity of time there, while

the skies cleared of reptile-birds, the swamps dried on the continental lands,

the sloths and saber-tooths had their day and sank in tar pits, and men ran

like white ants upon the hills.