Brain Lock: Free Yourself From Obsessive-Compulsive Behavior (13 page)

Read Brain Lock: Free Yourself From Obsessive-Compulsive Behavior Online

Authors: Jeffrey M. Schwartz,Beverly Beyette

Copyright © 1996, American Medical Association, from

Archives of General Psychiatry

, February 1996, Volume 53, pages 109–113.

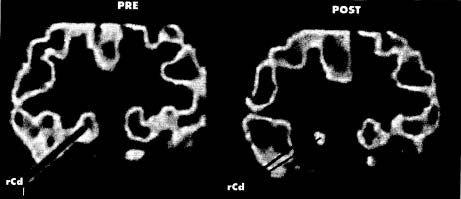

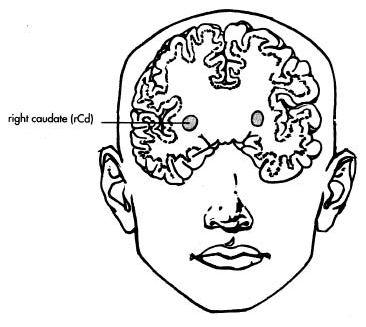

We have scientifically demonstrated that successful therapy, without drugs, can uncouple the “fixed-worry circuit” in the OCD brain so that the person can more easily stop doing those OCD behaviors. This knowledge has been a great motivator for people who are doing

the hard work of behavior therapy to change their responses to OCD’s false messages.

OCD is the first psychiatric condition in which a successful psychotherapeutic intervention that actually changes brain function has been documented.

When people with OCD do compulsive behaviors in a vain effort to buy a little peace, they are really only exacerbating their Brain Lock. When they systematically change their behavioral responses to OCD thoughts and urges, there is a concurrent change in the value and meaning that they place on what they feel. Before treatment, the intrusive thought might have said, “Wash your hands or else!” and the patients would usually respond by repetitive washing. After treatment, their response to the same OCD thought may be, “Oh, yeah? Go to hell!” By changing behavior, they are making alterations in brain function that, over time, result in measurable biological changes and a decrease in the intensity of intrusive OCD symptoms. It is important for patients and therapists alike to focus on these truths to help keep them motivated when the going gets tough.

As I’ve said, medication certainly has a role for those who need it to help them through therapy by decreasing their urges. (OCD and medication are discussed in Chapter Nine.) Using medication in treating OCD is much like using waterwings to teach children to swim. With waterwings, children can float unafraid, which helps the process of learning to swim. Then, you slowly let the air out of the waterwings until they are ready to go it alone. We use medication to help decrease the anxiety level of patients by suppressing those intrusive urges, so they can do their therapy and change their brain chemistry. Just as the swim teacher slowly lets the air out of the waterwings, we slowly bring down the dosage of the medication. Our experience in treating many hundreds of patients has been that after doing the therapy, the vast majority can get along very well with little or no medication.

KEEPING THE FAITH

Many people wonder about the role of faith and prayer in the treatment of OCD. Certainly, almost every person who has OCD has at

some time prayed for relief from the dreadful feeling their disease brings on. With deep humility, they may beg for any power, supernatural or otherwise, to grant them relief from the intense pain that obsessive thoughts and urges cause. What they need to pray for is not that the OCD symptoms will go away—they probably won’t—but that they will have

the strength to fight off their OCD

. There is an understandable tendency for people with OCD to become demoralized, even to begin to hate themselves because of feelings of guilt and inadequacy. One of the profound rewards of successful behavior therapy, especially from a spiritual perspective, is that people with OCD learn to forgive themselves for having these terrible thoughts because they realize the symptoms have nothing to do with their spirit or purity of mind and everything to do with a medical disease.

Using that knowledge to strengthen your will and bolster your confidence in the battle to “work around” these thoughts and urges is the critical point of mental intervention in OCD self-treatment. You need a tremendous sense of faith in your capacity to resist these urges, both to direct your mind away from the symptoms and to remove yourself physically from the site that triggers these symptoms—to leave the sink or walk away from the door. The acceptance that the painful obsessional thought is something that is beyond your capacity to remove—and that the thought is just OCD—enables you, the sufferer, to see yourself as a spiritual being who can resist this unwanted intruder. And always remember at least two principles. First, God helps those who help themselves. Second, you reap what you sow.

It is almost impossible to fight off an enemy as vicious as OCD if you are bogged down with feelings of self-hatred. A clear mind is required. Properly directed prayer can be very effective, but anything that helps you to develop the inner strength, faith, and confidence needed to reach that state of mindful awareness will further your progress along the road to recovery. The power of the Impartial Spectator can then guide your inner struggle to fight off the urge to do a compulsion or to sit, paralyzed, listening to some ridiculous obsessive thought.

Doing cognitive-biobehavioral self-treatment can truly be viewed

as a form of spiritual self-purification. Remember, “It’s not how you feel but what you do that counts.” In self-directed therapy, you concentrate your effort and use your will to do the right thing, perform the wholesome action, and let go of your excessive concern with feelings and comfort level. In so doing, you perform God’s work in a very real and true sense while you perform a medical self-treatment technique that changes your brain chemistry, enhances your function, and greatly alleviates the symptoms of OCD.

Strengthening your capacity to exert your spirit and will in a wholesome and positive way has far-ranging benefits that are, in many ways, even more important than merely treating or even curing a medical disease.

FINDING ANSWERS—WITHOUT FREUD

Here are a few of our patients’ descriptions of their battles against OCD:

KYLE

Kyle, a mortgage company employee, had struggled for years with violent thoughts of shooting himself, jumping out a window, or mutilating himself. Sometimes he thought he should just kill himself and get it over with. He prayed, “If there’s a weapon around and I do it, please don’t send me to hell.” His obsessions were “like a movie running through my mind, over and over.” He described his OCD as “a monster.” But through behavior therapy, he has learned, “I can bargain with it. I can stall it.” Crossing a street, he no longer has to push the WALK button a certain number of times, afraid he will be struck dead. He says, “Okay, I’ll push it again next year,” and he walks.

DOMINGO

Domingo, whose grab bag of obsessions included the horrifying feeling that he had razor blades attached to the tips of his fingers, said, “Every day, OCD is here. Some days it comes in waves. Some days are livable, some are miserable. On the miser

able ones, I tell myself, ‘You’re just having a bad day.’” Pasted to the mirror door of his bedroom closet is a color photo of an OCD brain, a PET scan—the same photo that’s on the jacket of this book. When things get rough, Domingo focuses on it. “I tell myself, ‘Okay, now that’s reality. That’s the reason that I feel like this.’” That gives him strength to cope and helps make his pain recede. “Once you know what you’re fighting,” he said, “it makes it easier.” Domingo is one of those whose brains we scanned. When he looks at his scan, he laughs and says, “It was pretty busy in there.”

ROBERTA

Roberta, who became fearful of driving because of unshakable thoughts that she had hit someone, first sought treatment with a Freudian therapist who suggested that there was something in her past that was causing her obsession. Looking into her past didn’t help her one bit. What did help her was behavior therapy. Once she understood that the problem was biochemical, she said, “I relaxed. I wasn’t as afraid. At first, it was like this thing had control of me. Now, while I can’t keep it from happening, I

can

tell myself, ‘This is a wrong message, and I feel I have control over it.’” Most days, she is able to drive wherever she wishes, no longer having to weigh her need or desire to go somewhere against her awful fears. “I just go on my merry way.”

BRIAN

Brian, the car salesman with the morbid fear of battery acid, also had experience with a Freudian therapist who diagnosed just about every mental aberration, but not OCD. One therapist tried to treat him with basic exposure therapy. Brian laughed as he recalled, “I walked into this guy’s office, and he had two cups of sulfuric acid on his desk. I said, ‘Adios, guy! I’m outta here!’ There was just no way I could do that.” Brian’s OCD fears and compulsions had become so overwhelming, he said, that “I just

wanted to crawl right out of my skin, just crawl right out.” He told one doctor, “I don’t own a gun and it’s a damned good thing I don’t because I would blow my brains out.”

In self-directed behavior therapy, Brian began using the Four Steps. He shook his head as he described what he went through. “It’s work, I’ll tell you, it’s work. It’s a war.” The moment of truth came when, on a new job at a car dealership, he spotted six palettes of batteries right outside his office door, inches away. His first instinct was to order them moved. Then he told himself, “No, you’ve just gotta put your foot down, take a stand, and fight.” He left the batteries there, and the batteries were still there the day he left that job. Brian knew that if he didn’t hold his ground, if he didn’t Relabel and Reattribute his fear of battery acid, “I would just have to keep running away.” He was even able to joke that the batteries were still there, “and I haven’t been eaten yet.” He tries to practice the Four Steps religiously, always reminding himself, “This is OCD. This is nonsense.” Sometimes he backslides. But if he lets his OCD get the upper hand, he knows, “Everything will wind up being contaminated in my mind, from the phone to the microwave oven.”

ANNA

Anna, the philosophy student, had been diagnosed by a therapist who told her that her jealousy and doubts about her boyfriend were “just a Freudian obsession with your mother’s breasts.” Though Anna knew that this was “totally stupid,” she didn’t know she had OCD until she was diagnosed at UCLA. She and Guy are now happily married, but they came close to breaking up because of her relentless and senseless questioning of him: What had he eaten that day? Who had he dated as a teenager? What did she look like? Where did he take her? With absolutely no cause to do so, she interrogated Guy over and over about whether he looked at girlie magazines and whether he drank to excess. Although Anna understood that she clung to certain insecurities because of past relationships with men who had drug or

drinking problems, it wasn’t until she learned that she had OCD that she began to understand her absurd actions.

In high school, Anna had become obsessed with Cheryl Tiegs after Anna’s first real boyfriend, who wasn’t very ardent in his affections, mentioned in passing that he thought Tiegs was good-looking. “This woman drove me mad,” Anna recalled. “It was making me physically ill.” Some time later, Anna learned that her boyfriend was homosexual, which explained why he wasn’t more amorous. But this knowledge only exacerbated Anna’s insecurities, and years later she would lie in bed with Guy and suddenly think, “What if my husband is gay?” Naturally, it was another of the questions with which she bombarded the poor man.

Each day, Anna would grill Guy about his activities, down to whether he had butter or margarine on his bread for lunch. If there were minute discrepancies in his answers, since he repeated them somewhat absentmindedly, Anna’s whole world would crumble “because there was one card in the house of cards that would fall down.” She couldn’t stop her questioning, even though she realized her behavior was “appallingly shrewish.”

Through our Four-Step self-directed therapy, Anna was gradually able to conquer her obsessions. She considered it a significant sign of recovery when a Victoria’s Secret catalog came in the mail and she was able to leave it lying around where Guy might see it. Now, if an obsession intrudes, she tells herself, “Okay, it’s not going to help me to dwell on this now. If it’s real, and there’s a real component, it’ll be clearer when the OCD is not intruding.” Of course, it never is real. This is another example of that crucial principle: If it feels like it might be OCD, it is OCD.