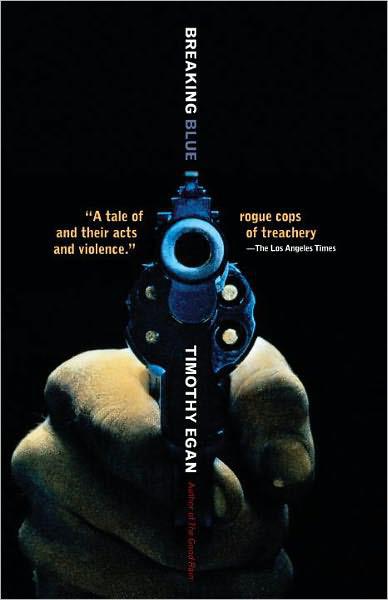

Breaking Blue

Authors: Timothy Egan

Tags: #General, #True Crime, #Non-Fiction, #Murder, #History

ALSO BY TIMOTHY EGAN

The Good Rain

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC

.

Copyright © 1992 by Timothy Egan

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Egan, Timothy.

Breaking blue / by Timothy Egan. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-80040-4

1. Murder—Washington (State)—Pend Oreille County—Investigation—Case studies. 2. Police murders—Washington (State)—Pend Oreille County—Case studies. 3. Police corruption—Washington (State)—Pend Oreille County—Case studies. 4. Bamonte, Tony. 5. Ralstin, Clyde. 6. Conniff, George, d. 1935. I. Title.

HV

6533.

W

2

E

36 1992

364.1’523’0979721—dc20 91-27848

v3.1

To Joni, for the time

There ain’t no sin and there ain’t no virtue.

There’s just stuff people do.

JOHN STEINBECK

,

The Grapes of Wrath

The following story is true, based on public records, newspaper and archival material, and the recollections of people who lived through the summer of 1935 to tell about it in the last years of their lives.

Acknowledgments

Prying this story from people who were around in 1935 was not nearly so hard as was tracking down the most basic of police documents from that era, most of which have disappeared. For help in the tracking, I am grateful to the staff at the Cheney Cowles Museum in Spokane, to the Newport Historical Society, and to Joan Egan. I owe much to Jon Landman in New York, who has the best eye for storytelling of anyone on West 43rd Street. I’m grateful to Carol Mann, for insight and guidance. At Knopf, my thanks to Ash Green, Melvin Rosenthal, and Jenny McPhee.

THE LAST ACT

OF LIFE

SEPTEMBER 1989

Judgment Day

W

HEN IT CAME TIME

for Bill Parsons to die, he crumpled into his wife’s arms and started talking about the things cops seldom share with the women in their lives. She ran her fingers through his hair, this silver thatch, and felt the faintness of life: a tired and congested heart following a directionless beat, torn-up lungs gulping from the plastic tendrils of a metal appendage, a body in full retreat. Here it was, an Indian-summer morning in a valley cut by the Spokane River, and he couldn’t take a breath of cool air. The wind blew down from the Selkirk Mountains, carrying a scent of the year’s final hay-cutting and apples pressed to cider; his oxygen came from the pharmacy, bottled.

The doctors could keep him from dying, but they could not make him feel alive. After thirty-five years of service to the city of Spokane, Washington, the former chief of police had a first-rate pension and medical plan, but it seemed to amount to nothing more than an open ticket to see more urologists and respiratory therapists—the young men in running shoes waiting to stick something new up his ass or down his throat. Retirement was supposed to be about poker games in the light of a campfire, hip waders instead of tight shoes, chasing elk through huckleberry thickets, not about chrome trays and hospital

gowns and a daily breakfast of color-coded horse pills. He seldom left the doctor’s office feeling any better, just more burdened with stuff. The bottled oxygen, the stimulants and slow-you-downs—all this

crap

—for what? To sit in a trailer park, on the fringes of a city whose laws he’d once enforced, waiting for Oprah to come on the tube?

From his office beneath the Gothic tower of police headquarters, he used to look away and imagine a salmon fly floating down the Spokane River below, taking the bend in slow motion until—

thwap!

—a big brownie rose to snap the line. On the river that carried snowmelt from two states to the Columbia rode the retirement dreams of the former chief. In the inland Northwest, where the great coastal ranges blocked the rainstorms from the Pacific and the land was ripe with the kind of wildlife that most of America has lost, the outdoors was the only place for honest work and decent play. Ten minutes from the center of town, downstream from the raging falls, an old man could be Huck Finn again, lost in the eternal flow of the Spokane River.

Life was supposed to ebb away, like the river. But Parsons’s body answered to its own schedule, throwing in a heart attack and emphysema, payback from earlier years. Physical pain he could tolerate; the toll on his good name was something else. Suspicion, half-truths, a vague and unfinished story about corruption and death from another era—that was not the sort of thing a person wanted to leave behind. The body would not go cold before the gossip would harden to gospel.

A rancher’s son, born when followers of Chief Joseph of the Nez Percé still dreamed of driving homesteaders from the ponderosa pine forests and alfalfa fields of the inland Pacific Northwest, Edward W. “Bill” Parsons had seen the length of the twentieth century, only to have one incident, the worst mistake of his professional life, come back at him now. He started in police work at a time when bootleggers and Chinese numbers rackets could provide a patrolman with a healthy income on the side, and he got out just before crack dealers and the state lottery commission made a mockery of the Depressionera enforcement routine. When he retired, plotting a good life in the woods, serving on citizen boards and honorary panels, the chief

thought he had escaped with his reputation intact. Baby-faced Bill Parsons, rookie cop in 1935, silver-topped dean in 1970, leader of the state police chiefs’ organization, past president of the Fraternal Order of Police. But where were his brothers now, when he needed them? The secret Parsons had carried with him his entire career was coming out: people were whispering; it was in the papers, on television. And it wasn’t even

his

secret; yes, he was its custodian during his years on the force, but once he retired, he had passed it on—or so he thought. The damn thing belonged to the Spokane Police Department, an institutional responsibility. Why, he wondered in these last days of his life, should he have to answer for it? It wasn’t fair! Parsons had held up his end of the Blue Wall, keeping a silence that is the bond of his profession. Never, never, never had he spoken a word.

Confined by the limits of his collapsing body, Parsons longed for company, a few fellows who Knew What It Was Really Like. He used to go down to the Police Guild lounge for a snort and a memory blast. But, over time, most of the faces were unfamiliar, the common ground faded. Jerie asked some of the old boys from the station to visit her husband—“Just give the chief an hour of your time”—but few people came around to the trailer park on the fringe of town. It seemed obvious, though it took some time for him to believe it, that perhaps his popularity was entirely dependent on the uniform he had worn half his life. Now, he was so lonely it sometimes felt like physical pain, a powerful ache. In baggy clothes, no longer chief, Bill Parsons sat through his last year as a bored and pained bystander.

A few months shy of his eightieth birthday, nothing seemed to work but his conscience, the nag. Jerie held him, a frame of soft skin and weak bones. The prettiest man in the police department still had his eagle’s crown. He closed his eyes and fell back to 1935, when he was a rookie patrolman, natty in blue and tight collar, a .38 strapped to his side, polished boots, with a regular salary and a degree of respect few men could command during the darkest days of a time when everything seemed to have fallen apart, a low, dishonest decade, as the poet W. H. Auden had called it. In whispered words and broken cadences, he started telling Jerie about that other September fifty-four

years earlier, and the truth about a story that was just now starting to emerge.

T

HE MAN

who had stirred Parsons, lighting fires under the dead and the near-dead, lived alone in a decaying three-story brick building—a former office, his home—about seventy-five miles north of Spokane, in the border hamlet of Metaline Falls. Anthony G. Bamonte had spent the last year thinking about September 1935. He was reasonably sure that he knew what Parsons, and much of the Spokane Police Department, had been trying to hide for more than half a century. A few questions remained, though, to keep him awake. Bamonte was forty-seven years old, trying to rebuild a life pained by a pending divorce and the political pressures of his job. More and more, he retreated into obscure books and yellowed newspapers from sensational times. His world was falling apart, his wife gone, his boy estranged from him, his job in jeopardy; but when he worked the past, everything he touched came to life.

Bamonte was pursuing a master’s degree at Gonzaga University, the old Jesuit college that was built on the banks of the Spokane River at a time when most of the people who lived near its shores were native Spokane or Coeur d’Alene Indians. A logger’s son, raised in canvas tents and backwoods cabins without plumbing or electricity, Bamonte had a passion for history, perhaps because the stories of rough-edged men wrenching a living from a land so recently undraped from its glacial period were not that far removed from his own early years in the inland Northwest. Bamonte could look at a meadow above the Pend Oreille Valley, a country where he built fifteen log homes, and he would see a tribe of Kalispel Indians gathered to spear salmon and swap pelts with the Hudson’s Bay Company. The past was not dead, he believed, and the dead were not powerless.

When he enrolled in the master of organizational leadership program at Gonzaga, his thesis idea seemed unique to the professors. He wanted to do a history of all the sheriffs in Pend Oreille County (pronounced “Pond-O-Ray,” the name was a legacy of French-Canadian fur trappers, a reference to the shell ornaments,

pendants

d’oreille

, worn in the ears of the natives) and the major crimes of their times. Except for his tour in Vietnam in the early 1960s and a few years in Spokane, home for Tony Bamonte had always been the Pend Oreille, where nine thousand people live in a county half the size of Connecticut. The land is crowded with tall pines wrapped in jigsaw pieces of red bark, holding to the rumpled spine of the Selkirk Mountains. Grizzly bears, among the last of the biggest land mammals left on the continent, still roam the woods, occasionally tearing up gardens or chasing farm animals. Although the Coeur d’Alenes, the Spokanes, the Nez Percés, the Kalispels, and visiting Blackfeet and Crows hunted elk and pulled chinook salmon from waterfalls, the human presence is recent, and negligible. Washington’s only significant populations of moose, caribou, and wolves live in the county. What they have in the Pend Oreille is a vastness where time is never forced. The valley was not settled by whites until the mid-1890s, when a sawmill was stitched to the banks of the river on the Washington-Idaho border. A hard town of loggers, miners, saloonkeepers, and chow merchants formed around the mill.