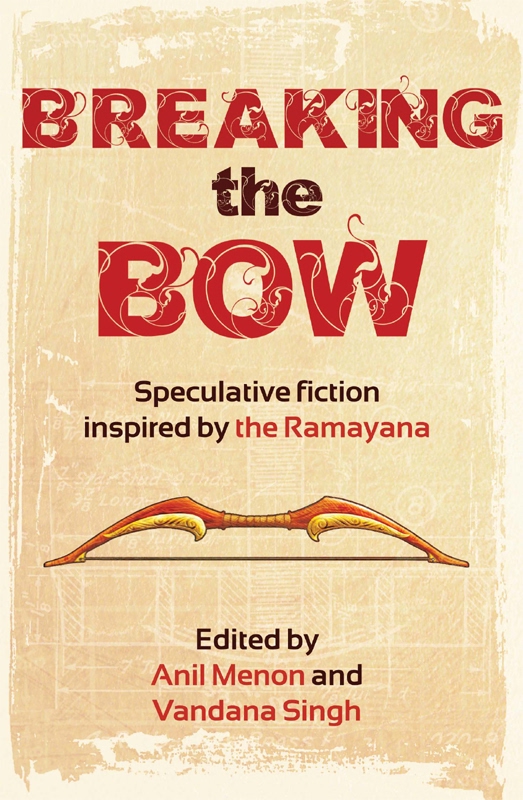

Breaking the Bow: Speculative Fiction Inspired by the Ramayana

Read Breaking the Bow: Speculative Fiction Inspired by the Ramayana Online

Authors: Edited by Anil Menon and Vandana Singh

Tags: #feminism, #women, #gender, #ramayana, #short stories, #anthology, #magic realism, #surreal, #cyberpunk, #fantasy, #science fiction, #abha dawesar, #rana dasgupta, #priya sarukkai chabria, #tabish khair, #kuzhali manickavel, #mary anne mohanraj, #manjula padmanabhan, #india, #sri lanka, #thailand, #holland, #israel, #UK, #USA, #fiction

ZUBAAN

is an imprint of Kali for Women

Zubaan

128B Shahpur Jat

1

st

floor

New Delhi 110 049

www.zubaanbooks.com

First published

by Zubaan, 2012

Copyright © Anil Menon and Vandana Singh, 2012

Copyright © individual essays with the authors

All rights reserved

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

eBook ISBN: 9789383074174

Print source ISBN: 9789381017043

This eBook is DRM-free.

Zubaan is an independent feminist publishing house based in New Delhi, India, with a strong academic and general

list. It was set up as an imprint of the well known feminist house Kali for Women and carries forward Kali’s tradition publishing world quality books to high editorial and production standards. ‘Zubaan’ means tongue, voice, language, speech in Hindustani. Zubaan is a non-profit publisher, working in the areas of the humanities social sciences, as well as in fiction, general non-fiction, and books

for young adults that celebrate difference, diversity and equality, especially for and about the children of India and South Asia under its imprint Young Zubaan.

Typeset by Jojy Philip, New Delhi 110 015

Printed at Raj Press, R-3 Inderpuri, New Delhi 110 012

Introduction

Anil Menon

Introduction

Vandana Singh

The Ramayana as an American Reality Television Show: Internet Activity Following the Mutilation of Surpanakha

Kuzhali Manickavel

Exile

Neelanjana Banerjee

Making

Aishwarya Subramanian

The Good King

Abha Dawesar

The Mango Grove

Julie Rosenthal

Game of Asylum Seekers

K. Srilata

Day of the Deer

Lavanya Karthik

Weak Heart

Tabish Khair

Sita’s Descent

Indrapramit Das

Great Disobedience

Abirami Velliangiri

Test of Fire

Pervin Saket

The Other Woman

Manjula Padmanabhan

This, Other World

Lavie Tidhar

Fragments from the Book of Beauty

Priya Sarukkai Chabria

Kalyug Amended

Molshree Ambastha

Sita to Vaidehi—Another Journey

Sucharita Dutta-Asane

Petrichor

Sharanya Manivannan

The Princess in the Forest

Mary Anne Mohanraj

Sarama

Deepak Unnikrishnan

Regressions

Swapna Kishore

Machanu Visits the Underworld

Victoria Truslow

Oblivion: A Journey

Vandana Singh

Vaidehi and Her Earth Mother

Pratap Reddy

Falling into the Earth

Shweta Narayan

Anil Menon

A long time ago, the story goes, a young prince, the heir to a great South-Asian kingdom, threaded Siva’s mighty bow and won the heart of a brave princess. The story of what happened next, a story which begins where most love stories end, the story of the

Ramayana,

has been

told and re-told countless times over the centuries. Hold on to a story long enough and it begins to make a people. The long shadow of the

Ramayana

explains why a popular Indian brand of cockroach poison is called

Laxman Rekha Chalk;

why a recent Bollywood superhero movie should have a villain named Ra-One; and why for some Indians the word

Ram-rajya

(Rama’s State) is a political ideal and not

a mythical era. South-Asians have held on to this tale.

However, the twenty-four stories in

Breaking the Bow

are not about holding on to this great and ancient tale. They are about letting go and making ourselves anew. The

Ramayana

is important to this project as an inspiration, a context. To take the road not taken requires a road that has been taken. We are (mostly) interested in the road

not taken.

This is very hard to do with the

Ramayana.

The idea that there is “the”

Ramayana

is one of those South-Asian facts: true wherever it is not false. As A.K. Ramanujan’s wonderful must-read essay

300 Ra-mayanas

shows, there are many Ramayanas. The tradition is to depart from the tradition. There is the Jaina

Ramayana.

The Kashmiri

Ramayana.

There is Brij Narain Chakbast’s Urdu Ramayana.

The Muslim poet Masihi’s Persian Ramayana begins with traditional Islamic invocations. If the great archeologist H.D. Sankalia is right, there is a Lord Rama story in the

Zend-Avesta.

Kamban’s Tamil version,

Kambaramayana,

would surprise fans of Tulsidas’ Ramayana for the respect it accords Lord Ravana. Kamban’s radical influence can be seen in works as recent as Mani Ratnam’s

Raavan

(2010). Even

more radical is the

Chandravati Ramayana.

Composed by a sixteenth-century female poet and bhaktin, it is mostly about Sita; a feminist Ramayana. And this is just the subcontinent proper. There are the Ramayanas from Thailand, Malaysia, Burma and Cambodia. There are many

Ramayana

versions, many departures.

What usually happens in such a situation is that a tradition develops in the method of

departure. The story is re-imagined with shifts in points of view, minority characters are given a voice, value systems are inverted, settings are modernized and/or the story is relocated in space and time. A few stories in this collection also adopt some of these traditional techniques. Despite our suggestion that writers avoid straightforward retellings, some of the Ramayana’s characters were not

so easily silenced. For example, Lord Ravana’s sister Surpanakha—mutilated by Lord Rama and Lakshman for her inappropriate amorous advances was the subject of many sympathetic treatments. It was the quality of these retellings, not their ideologies, that persuaded us to include them.

Still, such retellings are the exception. We are aiming for a different kind of departure. Most of the stories

in this anthology belong to the genre of speculative fiction. Spec-fic includes science fiction, fantasy, magic realism, slipstream, surrealism, neo-modernist and postmodern lit, and many other sub-genres.

What make a story speculative? A simple answer, not entirely accurate, is that a speculative story is a non-realist story. In a realist story, the story’s context—the stuff that needn’t

be told- is this world, the actual world, common-sense world. In a realist story, if two lovers meet in Navi Mumbai, the reader can be reasonably certain they are meeting in Maharashtra, India. But in a non-realist story, there are no such guarantees.

Navi Mumbai

could a video game, the belly of a whale or the renamed capital of Sweden.

Just as topology evolved out Euclidean geometry by relaxing

the set of permitted transformations, speculative fiction evolved out of realist fiction by relaxing various constraints. Stories no longer need to be about human or pseudo-human characters. They don’t need to be set on

this

earth. They don’t need to be located in the past or the present. They don’t need to be written in any known human language. They don’t need to respect science or sense . Their

telling could be as rigorous as a mathematical deduction or as mischievous as the square root of a cheeky orange. Such freedom is challenging, not to mention frightening. To use an old Sanskrit term, it takes a certain chutzpah.

The ancient South-Asians had chutzpah. They imagined our universe as existing for a duration of 311 trillion years (100 Brahma years), about 23, 000 times larger than

the scientific estimate for the current age of the Big Bang universe (~ 13.5 billion years). They imagined multiple universes, frothing in the event-sea of creation and destruction. They imagined space and time as being illusory in the absolute and relative across the sea of universes. They imagined consciousness in all of matter, not just human beings. Divinity didn’t frighten them. The Rig-Veda

ex presses doubt on the omniscience of the creator. The ancients imagined weapons that could flatten mountains, unravel minds, devastate entire armies, destroy worlds and even annihilate the gods themselves.

The South-Asians were also fascinated with language. As the linguist Frits Staal remarked, what geometry was to the Greeks, language was to the ancient South-Asians. This fascination,

combined with their speculative imagination, led to stories that pushed the boundaries of what was possible with language: self-reflective stories, meta-fiction, fractal stories, frame stories stacked eight or nine levels deep, stories in which reality and fiction merged seamlessly, stories that encoded other stories, stories which questioned embodiment, gender and identity…

Of course, as in

all feudal societies, the storytellers were not to disturb the sleep of the privileged few. Predictably, the stories suffered. They could not explore moral, political or social issues with much honesty. The truth was fixed in advance. The stories were afraid to question anything directly. Imagination had to hide in women’s tales, live in kitchens, speak in regional tongues, sink underground. In

time, there was no need to worry about offending anybody; when have the mute offended the deaf?

In this context, A. K. Ramanujan’s comment that no Indian— at least, no Hindu- hears the epics for the first time acquires an ironic flavor. The Ramayana with its fantasy tropes should arouse the

adbhut

rasa—the savor of wonder—but it cannot, because in India the pleasure of a first contact with

the epics is not possible. Or more accurately, the savoring of the epics as a novel experience is not possible. The epics come in many diverse versions, but diversity is not novelty. We need the novum for wonder, and that is precisely what tradition cannot offer.

But speculative fiction can. This was brought home to us by Pervin Saket’s

Test of Fire,

written at a fiction workshop Vandana, Suchitra

Mathur and I had conducted at IIT-Kanpur in 2009. I wasn’t excited to discover that the story had Sita as its protagonist. I had read quite a few stories centered around Sita. In fact, just before coming to Kanpur I had read Namitha Gokhale’s anthology on Sita. Pervin’s interpretation of Sita didn’t

break any taboos. In its disappointment at Sita’s treatment, it wasn’t particularly radical. Yet

Pervin’s Sita felt new. It soon became clear that the other participants also sensed a difference. Pervin, with a clever choice of setting, had moved an ancient tale virtually forward in time. The result was a taste of the

adbhut rasa,

the quintessential taste of science fiction.

Pervin’s story reminded us that we once again had a literature un afraid of the imagination. We began to wonder

about the sort of departures that speculative fiction—not just science-fiction—could make possible. Consider Arthur C. Clarke’s use of the

Odyssey

in his novel 2001. Superficially, there is little in Clarke’s novel that reminds one of the

Odyssey.

Yet unlike many retellings, Clarke’s Bowman recaptures the existential loneliness of Odysseus. Perhaps that’s because our horizons are now pinned to

outer space, and as we stand with Clarke’s Bow man we become Odysseus gazing outwards at the glittering infinite sea.

Clarke’s telling was as elegant as his setting was essential. We wondered if something similar would be possible with our own great epic.

I am glad to report our authors rose to the challenge. This is an inter national effort. We have authors from India, Sri Lanka, United

States, Britain, France, Holland and Dubai. Some like Manjula Padmanabhan, Tabish Khair, Priya Sarukkai Chabria and Abha Dawesar are very well known, but we also have many new voices. The result is a one-of-a-kind anthology. Delicate fantasies such as Shweta Narayan’s

Falling

or Aishwarya Subramaniyan’s

Making

sit next to K. Srilata’s philosophical

Game of Asylum Seekers,

Pratap Reddy’s murder

mystery

Vaidehi

and Sucharita Dutta-Asane’s magic realist

From Sita to Vaidehi.

Sometimes, like the long-lost twins in the Hindi movie

Ram Aur Shyam,

stories mirror each other because they are so different. Priya Sarukkai Chabria’s poetic

Fragments From The Book of Beauty

is city-twin to Molshree Ambastha’s amusing

Why Me?

Molshree’s

story, written in the heart felt, irony-free style characteristic

of Ram-leelas, perhaps has the best last line of all the stories.

We found other mirrors. Kuzhali Manickavel’s

The Ramayana As An American Reality Show

is in its way as hallucinogenic as Tori Truslow’s

Machanu Visits The Underworld.

Similarly, Neelanjana Banerjee’s

Exile

parallels Lavie Tidhar’s cyberpunk

This, Other World.

The desolate alternate history of Abirami Velliangiri’s

Great Disobedience

meets the grim archeology of Swapna Kishore’s

Regressions.

You will find many voices, many novums, many

rasas.

Bring a large spoon.

Acknowledgements: All editors should be so lucky as I was to have a co-editor with the sensibility and judgment of my friend Vandana Singh. Our anthology also exists because of the investment and imagination of the people behind Zubaan Books, especially Urvashi

Butalia and Anita Roy. This independent press has the stoutest heart in all of Indian publishing. A heartfelt namasthe to Shweta Tewari for shepherding us through the process; our many bleats and excuses must have been in credibly annoying. And finally, Saras, for making my orbits around the sun such fun.