Bright Lines

Authors: Tanwi Nandini Islam

PENGUIN BOOKS

BRIGHT LINES

TANWI NANDINI ISLAM

is a writer, multimedia artist, and founder of Hi Wildflower Botanica, a handcrafted natural perfume and skincare line. A graduate of Vassar College and Brooklyn College’s MFA program, she lives in Brooklyn.

Praise for Tanwi Nandini Islam’s

BRIGHT LINES

“

Bright Lines

is the most daring, emotionally dense work I’ve ever read by a debut novelist. I can’t remember the last time a novel kept me breathless, wandering and reconsidering the decisions of my own life. Tanwi Nandini Islam has created a fictive world where race, place, desire, violence, and deception beautifully cling to nearly every page, and really every part of her Brooklyn and Bangladesh. She is completely unafraid of insides and outsides of the characters she’s created. I dreamt about Ella and Anwar for weeks long after I finished the book. I’m sure the characters here, and the actual range of Islam’s talent, will wonderfully haunt readers for a lifetime.

Bright Lines

is brilliant and absolutely soulful.”

—Kiese Laymon, author of

Long Division

“Whether it’s entirely fictional or not (and I really don’t care) the New York City of Tanwi Nandini Islam’s novel is the one I want to live in! What a radiant, abundant, worldly, sharp, and spirited novel! And what a good and powerful imagination, heart, and soul seems to have produced it.

Bright Lines

is very special.”

—Francisco Goldman, author of

Say Her Name

“Tanwi Nandini Islam is among an emerging generation of American writers giving voice to people, places, and concerns that have escaped the notice of the mainstream. Such is the range of her talent that in her first novel,

Bright Lines

, Islam shows us two locales, Brooklyn and Bangladesh, that are as varied and vibrant as they are restrictive and horrible, no small achievement. Hats off!”

—Jeffery Renard Allen, author of

Song of the Shank

“Every detail in this rich novel is evocative of transformation. . . . A sensitive and subtle exploration of the experience of gender nonconformity across cultures . . . A transcontinental, transgenerational tale of a family and its secrets.”

—

Kirkus Reviews

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright © 2015 by Tanwi Nandini Islam

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint an excerpt from “Dhaka Nocturne” from Seam by Tarfia Faizullah. Copyright © 2014 by Tarfia Faizullah. Reprinted with permission of Southern Illinois University Press.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Islam, Tanwi Nandini.

Bright lines : a novel / Tanwi Nandini Islam.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-101-60060-3

1. Young women—Fiction. 2. Family life—Fiction. 3. Domestic fiction. I. Title.

PS3609.S55B85 2015

813’.6—dc23

2015011851

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

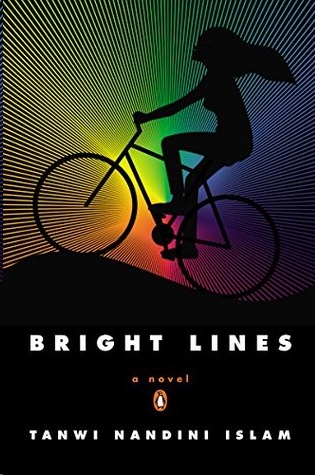

Cover design and illustration: Colin Webber

Version_1

Praise for Tanwi Nandini Islam

For my water, fire, and earth

Ma, Bajan, and Prom

Brooklyn

Your house shall not hold your secret nor shelter your longing.

—Kahlil Gibran,

The Prophet

G

irls, everywhere. Anwar Saleem stared brazenly at the flock that strode down Atlantic Avenue. He wondered if they noticed him sucking in his paunch, as he stroked the last ribbon of lavender paint across the awning of his apothecary.

LOTERÍA Y CIGARILLOS Y SE HABLA ESPAÑOL

disappeared into the settling twilight, erasing the last traces of the previous owner’s bodega. Anwar wiped his brow. A band of paint stiffened on his forehead. He climbed down, light-headed from the fumes.

On that first Saturday of June, everything in Brooklyn, everything except the sun, seemed to rise. Around the corner, on Third Avenue, petrol vapors blazed from cars in standstill, and traffic shimmered as if recalled in a dream. Trails of a street hawker’s incense disappeared into the scaffolding of an art deco phallus, where pigeons clamored in its eaves. Anwar’s Apothecary, sober and secular, nestled between Ye Olde Liquor Shoppe and A Holy Bookstore. A shout from the apartment upstairs startled Anwar enough that he nearly lost his balance.

* * *

“Thas not bad for business, now is it, Anwah?” called out the Guyanese street hawker, Rashaud Persaud, from his table down the block.

“Got a very good feeling about this color, my friend!”

“Naw, man, the fire escape! A girl on da move!” Rashaud laughed and pointed to a young girl climbing out of the window above the apothecary.

The girl hopped down the fire escape, her rump facing the street. Anwar craned his neck to see. She peeled off her hijab, revealing hair cropped as short as Audrey Hepburn’s. Mad dash toward the train; the girl did not look back. A fantasy sobered him: Charu the Runaway—slinking outside with her singing hips, those taunting kohl-painted eyes—ready to meet Internet confidants.

He shook this image of his younger daughter from his mind. They’d been having some trouble lately; she was moody, but she was going to NYU—that counted for something, right? Anwar looked once more to admire his brand-new storefront. The color was—

feminine

—but this last bit of paint could liven up their bathroom walls, which had become tinged gray with neglect. His wife, Hashi, would disapprove. She hated

pink-tink

, as she told him every time he wore his beloved polo shirt. She rhymed her displeasure:

skinny-tinny

,

Spanish-Tanish

,

sex-tex

. And they always began with the letter

T

.

Rashaud helped Anwar pull down the heavy, screeching gate.

“Needs some grease,” said Anwar.

“Try this.” Rashaud smacked him a high-five, pressing a Ziploc bag into his palm.

“Trail mix?”

“Majoun. Dates, raisins, walnuts, hash, and honey.”

“Thank you,” said Anwar, shaking Rashaud’s hand good-bye. It was curious how they’d known each other for almost ten years, but how little he knew about his friend. Rashaud had been hawking since he was eighteen, after some problems at home with his mother. But that was as much as he knew. Anwar handed him a

New York Post

from his back pocket. “And you take this. I’ve gotta quit reading this shit. Gives me nightmares about freak accidents and Mets games.”

* * *

As Anwar made his way home, he nibbled on the majoun. Sweetness coated his tongue. He unbuttoned one more button of his cotton plaid shirt, to let the evening breeze in. He surrendered to the humdrum of dusk, and listened as the voices, wares, wisdoms, and gods changed.

Coralline tendrils of cloud revealed a gaping hole where the sun

had been. As he walked down Hanson Place and crossed onto Fulton Street, eateries changed names as frequently as bandits. Farther down on Fulton, he passed a mosque with all the exterior charm of its neighbors, a 99-cent store and a bodega. Anwar never ventured there, and strode past the hennaed beards.

He did not believe in the god of these men.

Years past mingled with the unknowns of tomorrow on these evening walks home. He had lived atrocity during the 1971 war in Bangladesh, questioned the Supreme for allowing it. Thirty-two years later and still the ugliness of the war stayed with him, a dull ache, for the most part. The life he managed to have unnerved him: Hashi, Charu, his home; and of course, his elder daughter, Ella, who could not be called beautiful, but was on the

inside

. He pictured the perfect end to his day: a cold shower, then sitting in his studio, penning the memoir he never could start, about a pair of vagabonds during the war.

As he left-turned onto Cambridge Place, a maze of dominoes collapsed, each tick synchronized with the blinking eyes of the hustlers who ruled this corner. They nodded at him and he nodded back. There was nothing like this, the brownstone streets of his neighborhood. Children ran through an unleashed fire hydrant, hopscotch chalk erased in the wasteful gush of water. The aroma of grilled burgers brought tears to his eyes; he missed red meat.

As Anwar walked up to his brownstone on the corner of Cambridge Place and Gates Avenue, a hibiscus blossom landed by his feet. He had believed the tree would induce restful sleep in Ella, who struggled with insomnia. Within a year, it was already five feet tall; now, after ten years, it was taller than the house. Ella had slept peacefully, he believed, ever since.

It’s good to be high

, he thought, running his tongue on his teeth for remnants of the majoun.

He saw a solitary light in the kitchen. His wife’s beauty salon, the eponymous Hashi’s, was closed for the day. His third-floor tenant’s apartment: lights off. He mouthed her name,

Ra-mo-na Es-pin-al.

She worked the night shift today. No glimpses until morning.

Anwar cleared his throat as if to give a speech, but decided to watch the scene in the kitchen window.

His wife, Hashi, cast a fistful of onions into a pot, then several pinches of spice. She dipped a spoon into another pot and had a taste.

She closed her eyes and took a deep breath, then yelled, “Charu! Charu!” A minute later, their daughter Charu entered, giving Hashi a light hug from behind. Hashi turned to look at her.

Anwar tiptoed into the house, hoping to surprise them. He paused for a moment, in the darkness.

Do not enter

, he thought, suppressing the urge to giggle.

From this angle, Hashi’s back was turned. Staccato chopping of carrots filled the room, breaking his reverie. The pot of onions and turmeric hissed in canola oil, splattering grease onto the wall. Charu sat at the table, staring at an array of objects arranged like a daisy on the plaid tablecloth: a pile of empty cigarette packets, some rather compromising photos of Charu at the beach, and the prize, in the center: a condom wrapper, empty of its goods.

“Do—you—want—to—

die

?” he heard Hashi say.

Charu protested, “Ma, I told you! I was at the beach—that’s what people wear to the beach! Those are my cigarettes from a long time ago—I quit! The condom was from sex ed—I just wanted to see what it looked like!”

“You—are—

not

—my—daughter—You—are—

nothing

—like—me,” Hashi said, her back pumping up and down as she chopped.

“Ma,” Charu implored.

“Nothing!”

Anwar decided this was the moment to walk in.

“Er, what is happening, ladies?” he asked. He swiped a carrot from the cutting board. A second later and Hashi would’ve severed a fingertip.

“Your daughter tells lies and your daughter is doing sex and your daughter is doing smoking and your daughter is not mine,” Hashi said. She turned to look at Anwar. She set down the knife and crossed her arms, as if waiting for his response.

Anwar stared at Hashi, and then at their child, back and forth. Hashi’s hair was pulled back in a severe bun, her cheeks flushed with anger. She was yellow-skinned, slender, eyes sharp as a hawk’s; he still glimpsed traces of that haughty girl he’d been incensed with back when he knew her as his comrade Rezwan’s little sister. And Charu, skin tanned by these secret beach excursions, womanish curves she’d inherited from neither him nor Hashi. He imagined Charu’s visage as his own mother’s. He couldn’t remember; she’d

died before he’d known her breast. The sole photograph of his mother had been eaten by the elements, marring her face.

Charu’s enormous eyes were dead cold. It was a look that often corrupted his daughter’s sweet face. Long gone were the days when they rode the subway all the way to Queens for singing lessons.

“Hashi, I am sure Charu’s explanation is sufficient,” he said.

“No!” Hashi spat.

Guess that’s the wrong answer.

“No dinner. Charu will be alone tonight, and I won’t hear another word.”

“

Arré

, Hashi, it’s not fair—she is a growing girl. She must eat.”

“Fine by me!” yelled Charu. “I’m going out, anyway.”

“It’s almost nine at night. You aren’t going anywhere,” said Hashi.

“I’m eighteen. It’s Saturday night and I can do—”

“Shut. Your. Mouth. You’re not eighteen yet. You don’t even have a summer job. That would keep you in line.” A fleck of spit from Hashi’s mouth landed on her chin. Anwar thought better than to dab it away.

“I

told

you, I’m working. On my clothing line.”

“With what money? What fabric?”

Charu inhaled—Anwar knew this was the momentary calm before the storm. If he remembered correctly, Hashi had promised her leftover dresses and textiles from wedding parties.

“I’ll be gone soon enough. And I’m

never

eating this shit again!”

Charu shoved the dining table. Photos flew through the air like a dandelion clock. She ran into her father, and let go a wretched banshee shrill when he didn’t move out of her way. She forced her way past, stomped to her bedroom, and slammed the door. A minute later, the sound of objects being thrown against a wall—a stiletto, a dumbbell, anything within her reach. Then, a furious clanging of a Tibetan meditation bell, found at a German exchange student’s

schnickschnacks

sale.

Fathering a teenage girl, rough stuff

, thought Anwar, as he picked up a photo that had landed by his foot. In the photo, Charu’s lips kissed a dreadlocked boy’s ear: Malik. He felt a strange pang seeing the picture, jealousy tinged with admiration. He had suspected his younger daughter was dating Malik. The boy was his intern at the

apothecary, and

did

seem to be around the house often these past few months. The kids had grown up together in the neighborhood. Both were seniors at Brooklyn Tech; graduation was in two weeks. Charu would be headed to NYU, while Malik would be going to the New School. Anwar wondered if this meant they would continue their relations; it

was

pretty convenient. Malik was a soft-spoken, handsome Black boy. A solid, sensitive young man, better than what any stern, absentminded father could ask for. Anwar could stand him and that meant a lot.

Anwar wondered how Charu knew this feeling of love. It was further proof of their distance. Had the movies taught her?

Hashi bent over and picked up the photographs.

“I cleaned her room today and came upon this,” said Hashi. “She’s not growing up a good person. Look at this.” She pointed to another photo: bikini-clad Charu, eating a corn dog at Coney Island, pursing her lips around the thing rather—suggestively.

He missed Ella. She was a sophomore at Cornell’s agricultural school—a choice she’d made given her knack for tending their gardens. Ella remained remote, but within his grasp. She never intruded upon Anwar’s sensibility and listened to him about most matters. Her left eye had a tendency to turn this way and that behind her spectacles, and he wondered what she was looking at. If she were here, thought Anwar, her calm would keep Hashi’s nerves intact; she would find some way to make Charu laugh.

His two children were as different as their fathers had been.

* * *

“What on

earth

is on your face?” Hashi scratched his forehead with her thumbnail. Paint shavings tickled his nose. He’d forgotten about it.

“What is this? Paint? You walked home looking like some madman?”

“I decided to paint the shop today. Such a beautiful day outside—”

“So you decide on this color?” Hashi shook her head. With a damp corner of her apron she tried to wipe the stuff off, but it had crusted over. “Take a seat.” She clumped mashed scoops of rice, lentils, potatoes, and broccoli onto his plate, and sat across from

him. “It’s summer. Three months of this and I’ll be an old woman.” She chewed on an unripe tomato as if it were an apple.

“Dinner is very good,” said Anwar, licking the smorgasbord from his fingers. He remembered the enticing smell of grilled burgers on his walk home. “Let’s have some beef next time?”

“It’s a miracle I have energy to cook at all. I’m on my feet all day at the salon,” she snapped, slumping back in her chair. “It is summertime, which means weddings until death does me part.”

“Just suggesting a bit of protein,” said Anwar.

“If you want steak, you cook it.” Hashi took another hard bite of tomato, squirting the table with juice.

Anwar wiped the slimy seeds with his finger and licked them off.

“Disgusting, Anwar,” said Hashi, grimacing. “Aman Bhai called earlier. He asked if he could stay with us for a week or so. I guess the divorce is final?”

“I can’t understand why he doesn’t stay at a hotel or something, not like he doesn’t have the money.”

“Or he should try to work things out with Nidi.” Hashi started clearing the table. It took Anwar a minute to realize she was fixing a plate for Charu.

“Point is, he should find another place to stay,” said Anwar.

“He’s your brother. He let us stay with him for all those years—”

“We lived in his

basement

, and I paid him rent, yet never had heat.”

“Well, he may have money but you have me, Charu, Ella. He needs your support. Your love.”

“My love,” repeated Anwar. Bah! His brother did not need his

love

. Aman owned a triad of pharmacies around Brooklyn, and was indecently self-sufficient for a family member. His wife, Nidi, had fled after years of neglect. And as much as Anwar believed in support and love and other filial bonds, he and his brother did not share them.