Britannia's Fist: From Civil War to World War: An Alternate History (37 page)

Read Britannia's Fist: From Civil War to World War: An Alternate History Online

Authors: Peter G. Tsouras

Tags: #Imaginary Histories, #International Relations, #Great Britain - Foreign Relations - United States, #Alternative History, #United States - History - 1865-1921, #General, #United States, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #Great Britain, #United States - Foreign Relations - Great Britain, #Political Science, #War & Military, #Fiction, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #History

As if Dahlgren had not worries enough, the need to protect the Navy’s most secret experiment also weighed heavily on his mind. He had been testing two small submersibles designed to remove underwater obstacles and to plant torpedoes (mines). These ungainly beasts could never be allowed to fall into British hands. He had orders to sink them if necessary in the deepest possible water. It occurred to him that the boats were not entirely liabilities. He had given much thought to the use of submersibles after having had the Navy’s first submersible, the

Alligator

, repaired at the Navy Yard when he was superintendent, and he had requested the construction of several improved models. Now, more than a year later, he had been given delivery of two such boats for trials in the harbor of Charleston. He ordered that the submersible tender and the two boats accompany his flagship. His interest in submersibles had become even more acute two days earlier when the Confederate semi-submersible, CSS

David

, had attacked

New Ironsides

with a torpedo. The explosion had rocked the ship, which had been protected by its thick iron hull and armor casemate. Although the

David

had escaped, his men had fished two prisoners out of the water who had prematurely abandoned ship. They had detailed plans of the boat in their pockets.

7

Only if the British came after him through the bar did he stand a chance of defeating them, Dahlgren thought. Even then, they only had to retreat, stand off outside the bar, wait, and starve him out. Defeat would only be delayed. Only a decisive defeat of the British and their retreat could save him, and that, given the huge force Milne had assembled at Bermuda, was impossible. For a man whose Navy life had been a continuous quest for glory, the logic of this conclusion was bitter beyond belief. He could only redeem the coming disaster by following the order of Captain James Lawrence of the ill-fated USS

Chesapeake

in its battle with the HMS

Shannon

in 1813—”Fight her till she sinks!”

8

Dahlgren knew that a large number of ships had arrived to reinforce Milne at Bermuda but not exactly how many and what types (see

Appendix B

). All he had to go on was a London

Times

article of July that listed the ships of the Channel Squadron.

9

That had arrived courtesy of Brigadier General Sharpe, someone Lincoln had mentioned in his letter as doing important work in organizing information about the rebels. Now it seemed the good general was throwing a wider net, something Dahlgren was thankful for. He desperately wished he knew how many and which of the huge Channel Fleet’s four ironclad screw frigates Milne was sending against him. There wasn’t an officer in the fleet who had not heard of the leviathans HMS

Warrior

and

Black Prince

, which were more than twice as large as his largest ship, the USS

New Ironsides

. The

Defence

class

Resistance

and

Defence

were both half again as large as the American ship.

10

Though she was considerably smaller, she packed a greater punch than the British ships. She was armed with sixteen guns, fourteen of which were XI-inch Dahlgrens and completely outclassed the armament of the British ships. The American gun carriages and recoil systems were also far more efficient than those of the British models. Her armor was

Warrior

’s match as well. The British ships, however, had the speed advantage, able to move twice as fast as

New Ironsides

’s puny six knots.

The combat experience of the

New Ironsides

’s crew and those of the monitors would be a heavy weight in the scales of battle. Despite scores of hits from heavy Confederate ordnance, the

New Ironsides

emerged unscathed. The monitors’ combat experience against the harbor forts of Charleston had led to the introduction of a sheet metal inner sheathing to the turrets to prevent injuries to the crew from exploding rivets propelled by shot striking the outer surface.

Their twenty-foot-diameter turrets, with ten inches of armor in one-inch molded plates, were invulnerable to any ship-mounted guns in the world. Their hull armor was five inches, a half inch thicker than the

New Ironsides

and

Warrior

class, but the low freeboard meant most of the

hull would be under water. Deck armor was only an inch, thus requiring the expedient remedy of a layer of sandbags. Designs of the

Passaic

class had called for twin XV-inch Dahlgrens, but production lags forced them to substitute one XI-inch.

11

The turret was powered by its own small engine and could rotate 360 degrees in thirty seconds. Four iron beams in the deck served as slides for the gun carriages. “The slides would allow the guns to recoil a maximum of 6 feet, while the friction mechanisms could reduce the recoil to as little as two.” The carriages rested on brass rollers, so that large crews were not needed to run the guns out. Oval-shaped, armored gun ports swung open to allow the guns to fire and then were shut as soon as the guns discharged. Because the guns were muzzle-loaders, the long rammers had to be manipulated through the open gun ports. At such times, the turret would be turned away from the enemy, loaded, then turned again toward the enemy, and re-aimed.

12

This necessity was the greatest drag on the guns’ speed of fire, a problem the broadside ironclad did not suffer. The XV-inch gun in the monitor’s turret took an average of six minutes to fire, which could sometimes be reduced to a minimum of three. The XI-inch gun’s speed was about half that average. The broadside-fired Dahlgrens were another story entirely. The IX-inch could be fired every forty seconds, and the XI-inch every 1.74 minutes for about an hour. Comparing monitor and broadside ships, it was a trade-off between invulnerability and rate of fire.

13

There was no trade-off in punch. The XV-, XI-, and IX-inch Dahlgren shells with explosive charges weighed 350, 136, and 72.5 pounds, respectively. Their shot was even heavier, weighing in at 400, 169, and 80 pounds. The largest British shot, on the other hand, were the 110-pounder Armstrongs and the standard 68-pounder. Most British guns remained the venerable 32-pounders. Unlike the Armstrongs, the entire Dahlgren line was a byword in safety and reliability. The captain of the sloop the USS

Brooklyn

believed his IX-inchers to be well-nigh perfect and stated that “the men stand around them and fight them with as much confidence as they drink their grog.” Unlike most British guns, the Dahlgrens had been designed to fire both shell and shot, giving them a powerful versatility. Because of the

Monitor-Virginia

standoff the year before, Dahlgren had rigorously tested his guns against armor plate. He found that they could easily stand to increase their powder charges by 50 to 100 percent in order to easily drive holes through iron plate and wood backing of thickness and composition similar to the British

Warrior

class—“4- to 4.5-inch thick iron faceplate, bolted to about twenty inches of wood,

sometimes with an inch-thick iron back plate, set up against a solid bank of clay. In most cases, the Dahlgren shot penetrated clean through the target and embedded itself deep into the clay bank, even with the target angled steeply as fifteen degrees.”

14

The exploding shell was all the rage in naval ordnance, and no gun delivered the destructive charge against wooden ships better than the series of guns Dahlgren had devised. Against ironclads, the shells were less effective. Dahlgren’s guns were equally able to deliver solid shot. Dahlgren had also taken to heart the error that had prevented the original

Monitor

’s XI-inch Dahlgrens from punching holes right through the CSS

Virginia

’s iron casemate. Navy policy had mandated that a powder charge only 50 percent of the maximum tested charge be used. Subsequent tests by Dahlgren showed that not only could his robust guns fully stand the use of a 100 percent charge for long use but that they would tear 5-inch armor apart. At the time, Dahlgren had been particularly incensed by the comment of the British First Lord of the Admiralty that his guns were “idle against armor plate.”

During the Civil War two opposing schools of thought arose as to the best means of destroying armored warships. The “racking” school held that projectiles should smash against the ship, distributing the force of the blow along the whole side and dislocating the armor. Once the armor had been shaken off, the vessel would be vulnerable to shell fire. The “punching” school held that the projectile should penetrate the armor, showering the ship’s interior with deadly splinters in the process.… Dahlgren had concluded that racking was more effective against armored vessels than punching. Racking favored his low-velocity smoothbores over high-velocity rifled cannon.

15

Dahlgren had had the satisfaction in June of seeing the monitor USS

Weehawken

force the ironclad CSS

Atlanta

to strike its colors after hitting it at three hundred yards with only a few XV-inch shot. One shot alone dislodged the armor plate, sending a mass of iron and wooden splinters into the casement battery, spilling all the shot in its racks, and killing or wounding forty men.

16

The prize had been repaired at Port Royal and was on the way to Philadelphia when Dahlgren intercepted her. He asked for volunteers for a scratch crew and captain and found himself with more than enough seamen and with a score of ambitious

lieutenants who could smell promotion in the air. Of them he chose Lt. B. J. Cromwell.

17

As the

Philadelphia

was essentially unarmed, the admiral transferred his flag to the

New Ironsides

, from which he had commanded the previous attacks on Fort Sumter and the other harbor forts. His son, Ulric, had insisted on staying with the Navy rather than be sent ashore to join Gilmore’s troops. “

New Ironsides

has been in action more than any ship of the squadron. Where else would I be, Papa?” he asked. He had already hit it off with the ship’s captain, Stephen Clegg Rowan. An Irish immigrant, Rowan had joined the Navy in 1826 and fought “in the Seminole and Mexican Wars and had distinguished himself in the North Carolina sounds early in the Civil War.” Under his command, the

New Ironsides

became the most feared of all Union ships to the defenders of Charleston.

18

With

Flambeau

’s warning, a prearranged signal rocket from

New Ironsides

set the American squadron into motion. The lightest ships moved south to hug the shallow waters of the coast along Morris Island where the deeper draft British ships could not enter. These included eight steam gunboats, most of barely five hundred tons, and each armed with only a half dozen or so guns but sixteen of them Dahlgrens. He pulled his frigates and sloops inside the bar to join his ironclads.

The squadron had barely sorted out its formation when masts from at least a dozen ships dotted the horizon. Smoke plumes soon topped the masts as the engines were engaged. The inefficient engines gulped vast quantities of coal, and warships used sail as much as possible before switching to their engines for propulsion. Now that their objective was almost within sight, the British black gangs swung into work to stoke the fires that would give their ships that mobility and agility that sail could never match.

Finally, the last of the picket ships steamed through the bar to signal the flagship of the enemy’s imminent approach. One by one the masts increased until fifteen and more could be counted. The captain of the picket ship came alongside to report that he had counted four ships of the line, the rest frigates and smaller ships. The captain shouted through his megaphone, “But leading them is the biggest ship I have ever seen in my life, Admiral. She’s black from fore to aft. Must be the

Warrior

.” There was a stir on Dahlgren’s bridge among his staff, but the admiral’s face did not show a flicker of change. Captain Rowan just smiled. He had fought his ship and had the utmost confidence in her and her crew in

battle. He knew the

Warrior

’s captain, or for that matter, the captain of most Royal Navy ships at this time, could not say the same.

In fact, the picket ship’s captain had been wrong. The great black ship he had seen was not the

Warrior

but her sister ship, the

Black Prince

, commanded by Capt. James Francis Ballard Wainwright. An able officer, Wainwright had commanded his ship for more than eighteen months and, as a mark of his ability, had served as second in command of the Channel Squadron.

19

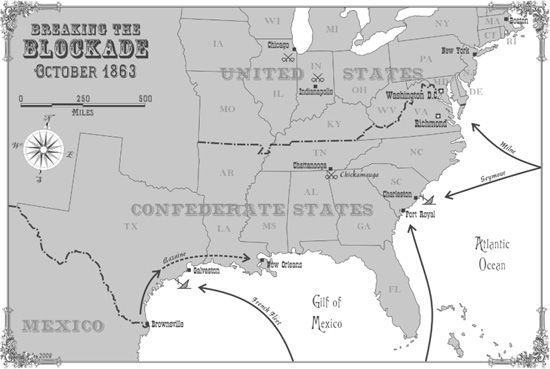

The squadron sailing toward Charleston was only the smaller part of Milne’s concentration at Bermuda. He shrewdly concluded that with the massing of the Royal Navys there was a clear indication that Charleston was its objective. The element of strategic surprise had never been realistic. He would have wagered to a certainty that the enemy knew the British were coming to Charleston. They already knew in Washington that the Royal Navy had seized Portland Harbor, though the town itself was still under siege. They were even more painfully aware that ships from Halifax were raiding the sea-lanes to New York and Boston. Their eyes were drawn north and south. It was toward the middle coast of the Atlantic seaboard that Milne was sailing with the bulk of his force—for Chesapeake Bay and the approaches to Washington and Baltimore. Admiral Cochrane had showed the way in 1814, inflicting great damage and even greater humiliation on the Americans by ravaging the shores of the great bay. Since they had seemed to have forgotten that lesson, he was determined to repeat it in such a forceful manner that it would linger and produce a national flinch whenever the thought of crossing the Royal Navy even occurred to them. Milne knew that the Union could never be physically destroyed, but it would give up the game if enough pain were inflicted. The second loss of their capital in less than fifty years would be a mighty weight dropped against the scales of their morale and will to fight.