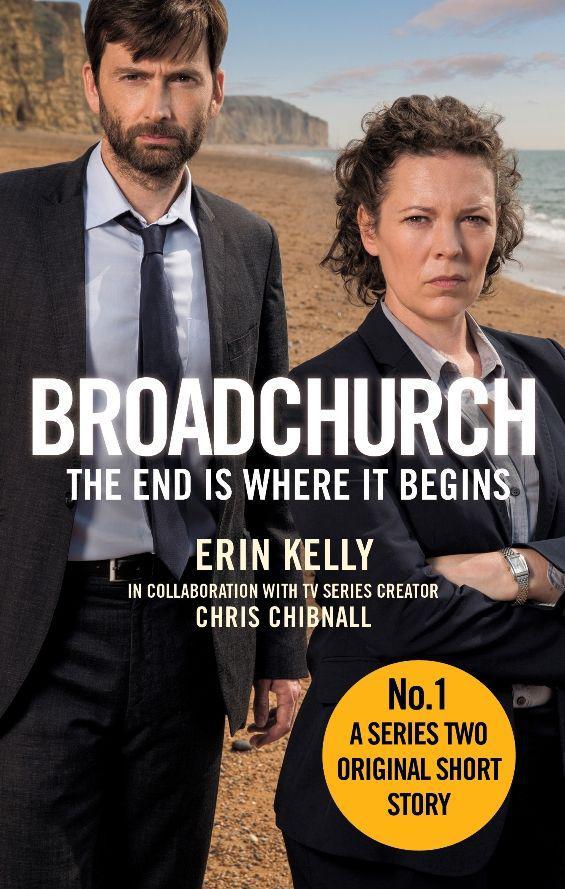

Broadchurch: The End Is Where It Begins: A Series Two Original Short Story

Read Broadchurch: The End Is Where It Begins: A Series Two Original Short Story Online

Authors: Chris Chibnall,Erin Kelly

Erin Kelly is the author of the first Broadchurch novel and four critically acclaimed psychological thrillers,

The Poison Tree

,

The Sick Rose,

The Burning Air and The Ties that Bind

.

The Poison Tree

was a bestselling Richard & Judy Book Club selection in 2011 and was adapted for the screen as a major ITV drama in 2012. Erin also works as a freelance journalist, writing for newspapers including

The Sunday Times

, the

Sunday Telegraph

and the

Daily Mail

as well as magazines including

Red

,

Psychologies

,

Marie Claire

and

Elle

. She lives in London with her family.

The Poison Tree

The Sick Rose

The Burning Air

The Ties That Bind

Broadchurch: The End is Where it Begins

A Series Two Original Short Story

Erin Kelly

Based on the TV series by Chris Chibnall

sphere

First published by Sphere in 2015

Copyright © Chris Chibnall 2015

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

ISBN 978-0-7515-5568-4

Sphere

An imprint of

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DY

An Hachette UK Company

Contents

They all know. They don’t say anything, but they all know.

The first time Ellie enters the staff canteen at Exmoor nick, her fellow officers set down their cups and cutlery, all the better to stare at her. It feels like there are hundreds of eyes on her, making something as easy as choosing between a bacon roll and an omelette an impossible task. Exmoor is a huge police station, three or four times the size of Broadchurch, and the canteen is shared with the county’s traffic division, who operate out of a giant garage next door. Ellie chose this place because she thought that big would mean anonymous. But it’s clear to her, as she picks up a bottle of water, that they know her history. She ploughs silence before her wherever she goes and trails whispers in her wake.

She carries her tray to the counter and imagines seeing herself through her new colleagues’ eyes. Even if they’ve got the right version of the facts, it must be hard to process what she’s doing here in Devon. Going back into uniform was Ellie’s choice, but it usually means a demotion. It’s shorthand for disgrace. As far as Ellie’s concerned, the uniform helps. Her collar and cravat let her hold her head up high, and she walks easy in regulation flat shoes. This is a move sideways, not downwards; she’s still a Sergeant. Her salary stays the same, and that’s important. Ellie’s staring down the barrel of single parenthood, paying for the childcare that Joe used to do for free. Resigning would mean sacrificing her pension, and with a good fifteen years’ service left in her, that’s not an option.

But there’s more to it than money. It doesn’t feel right to go back into CID until Joe’s been sentenced. She’s never told anyone this, but it feels like that way, she’ll be able to put Danny behind her. But going into uniform, that felt right. Ellie understands now what Hardy meant by atonement. By serving another community, she can atone for what Joe did to her own. Leaving the force, taking a sabbatical, all the other things that people told her to do: none of these was an option. This move is, above all else, a massive

fuck you

to Joe. Fifteen years, Ellie’s been on the force. When he took Danny’s life, he took Ellie’s best friend, her community, their eldest son. She will not let him have her career as well.

She’s got no appetite: she opts for a cereal bar in the end and eats it on her own at a corner table, her back to the room.

Ellie’s new partner is PC Cliff Kendall. His black vest showcases his barrel of a belly, and his close-cropped greying hair highlights his lack of a neck. Ellie immediately nicknames him Mr Potato Head but it’s hard to smile about that when there’s no one apart from Fred she can share the joke with.

‘You’re a lucky lady,’ Cliff says. ‘Twenty-three years I’ve been on this beat. This is basically my nick, lord of all I survey, although don’t tell the chief super I told you that. Ha!’ He laughs at his own non-joke in a way that suggests it’s not the first time he’s said this. She doesn’t join in, and his eyes narrow. Ellie can picture him off-duty, in T-shirts with sitcom catchphrases on them, bullying people into organised fun and practical jokes. ‘Anyway,’ he continues, ‘you couldn’t ask for a better tour guide to the fleshpots of North Devon.’ As he leads her through the unfamiliar corridors, Cliff tells her about his kids (in particular his outrage that PE isn’t compulsory at GSCE level), his journey into work and his cholesterol levels. By the time they’re in the car park, he’s moved on to his profound displeasure at having to share a canteen with the traffic division. ‘The most joyless, jobsworth bastards you’ll ever meet. The famous Black Rats.’ He twitches his nose and laughs again. ‘They’re even worse than internal affairs and that’s saying something.’ The wink he gives Ellie is clearly meant to be conspiratorial. ‘I mean, who trains for years and then thinks, I know, I’ll spend my life breathalysing old ladies?’ He chucks her the car keys. ‘I would say your carriage awaits, but you drive, you’ll want to get your bearings.’

When Cliff sits in the car, it bounces. Ellie’s barely started the engine when he tears into a steak slice. Flakes of pastry flurry around the front seat, settling like dandruff on Ellie’s epaulettes.

They drive through the countryside, Ellie taking in as much as she can of Cliff’s running commentary. After ten minutes, she finds herself yearning for Alec Hardy’s brooding and sulks. At least he was quiet. She wonders where Hardy is now: under a doctor’s observation somewhere, she hopes, contemplating the salvage of his own career from the confines of a hospital bed.

The closest Cliff comes to acknowledging her situation is saying, after clearing his throat several times, ‘I’ll tell you my ambition. To retire in this uniform. I’m proud to wear it.’ The grating joviality is entirely absent now; he’s almost snarling. He looks dead ahead, through the windscreen, and she can’t decide whether he’s telling her she should be ashamed or she shouldn’t, whether he’s trying to comfort her or put her in her place.

‘I couldn’t agree more,’ she says, trying to keep her reply as oblique as his statement. If he’s playing games, she won’t be drawn in. Instead, she concentrates on the lie of her new patch.

Everything’s on a different scale out here; instead of the soft hills Ellie’s used to there are wild purple moors with rocky crags. Even the sky feels bigger. It’s like she can sense the coast on either side, but there’s also a feeling of claustrophobia, a point of no return, on the ground, as the peninsular begins to narrow into Cornwall. After an hour on the road, Cliff suggests they head to ‘where the action is’.

As they roll over the crown of a hill Cliff gestures to a grey smudge on the edge of town. ‘There’s our destination. Bideford Chase estate. Ninety per cent of our shouts come from there. Biggest smack problem in the county. We don’t let our kids play with kids from the Chase. The law begins at home, that’s my motto.’

Ellie doesn’t suppose Alec Hardy has ever had a motto in his life.

Up close, the Bideford Chase estate is a grim little collection of low-rise flats centred around a bleak, almost Soviet-looking precinct where most of the shops are boarded up.

‘This’ll do, ease her in gently, there’s a nice big space for you there,’ says Cliff. Ellie makes a point of ignoring his detailed parking instructions and does it her way, a slow balletic reverse curve that gets her an inch from the kerb.

Cliff walks Ellie round the estate block by block. A girl of about six pushes a brick around in a toy buggy.

Ellie bends to her level. ‘Hello, what’s your name? Where’s your mummy?’

‘Fuck off, plod,’ says the little girl, before darting into the open front door of a ground-floor flat.

‘Another generation born and bred on the welfare state,’ says Cliff, and he’s off again.

After an hour of his social insights, Ellie starts to zone out and make her own observations. No wonder the kids are running wild; the playground has been vandalised so it’s just a mess of frames with no swings or roundabouts attached. The SureStart centre is boarded up, the entrance barricaded by an old mattress. Immediately Ellie starts thinking of outreach work; she’d forgotten that about uniform, how proactive you can be, the difference a friendly, familiar face can make. She feels old skills begin to uncurl after a long sleep. Maybe she’d been looking at her career all wrong, even before Danny’s murder. Maybe going full pelt for promotion after promotion isn’t what she was meant for. Community policing is why she joined the force in the first place.

The positivity doesn’t last long. Ellie’s mobile vibrates in her pocket: it’s Lucy, jerking her back into the mess of her real life. Ellie is both grateful to and resentful of her big sister, who’s keeping Tom fed and getting him to school and trying, in her limited way, to persuade him that the whole Joe thing isn’t just a plot concocted by Ellie to end the marriage. Tragedy and drama seem to have brought out Lucy’s maternal streak in a way that actual motherhood never did. Ellie swipes her phone to answer the call.

‘Where’s his swimming kit?’ barks Lucy, before Ellie can say hello. ‘He’s saying he needs trunks and goggles by

tomorrow

.’

Ellie’s heart plummets; she knows exactly where Tom’s swimming things are – rotting in a bag at the foot of his bed in their old house in Lime Avenue. She sighs; Cliff looks sharply at her. She turns her back on him.

‘Can you get him new stuff?’ she whispers down the line to Lucy. ‘He probably needs new trunks anyway, he’s shooting up all the time.’ She bats away the thought that he’s growing up without her. ‘Get age twelve to thirteen if you can.’

‘Put it on the slate, shall I?’ says Lucy, with no trace of irony.

‘Look, I’ve got to go, Luce,’ Ellie says, resisting the temptation to remind her of all the times she’s bailed her out; she needs Lucy on side now. ‘I’ll ring you tonight, as usual?’

She puts her head in her hands: long-distance parenting is tearing her apart. There’s been a series of little failures like this, since Tom moved in with Lucy. Ellie feels each of them in keen disproportion. School stuff was always Joe’s responsibility. He’s landed her in the shit in a million tiny ways.

‘You coping all right, love?’

‘

Love?

’ Ellie erupts. ‘What is this, the fucking seventies?’ Cliff goes dark red, but Ellie can’t tell if he’s mortified by his own thoughtless sexism or angry that he’s been called out on it. ‘I’m your superior officer, can I—’

Before Ellie can finish, her phone, still hot in her hand, goes again. Jenny, Fred’s childminder. She turns away from Cliff’s raised eyebrow and takes the call.

‘He’s done an up-the-back poo,’ says Jenny. In the background, Fred is whingeing. Ellie’s heart folds in on itself. ‘I thought you were bringing spare clothes? I haven’t got anything to dress him in.’ Ellie thinks; she remembers packing a bag last night. Then she sees it, clear as a photograph, in the boot of her car, in the station car park. A pulse starts to hammer inside her head. She loosens her cravat.

‘I’m sorry, Jen,’ she says. ‘Haven’t you got

anything

you can put him in?’