Broken Heart (34 page)

Authors: Tim Weaver

Tags: #Fiction, #Thrillers, #Crime, #Suspense, #Mystery & Detective, #General

‘Have you really seen all of the films he made after 1979?’ I asked.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘All eleven of them.’

Walker studied me for a moment, concern in his face, perhaps thinking that he’d entrusted the secrets of his Hosterlitz biography to someone unstable; a man for whom there was no clear path from one question to the next.

‘What do you make of the way they end?’

‘The repeated ending? I don’t know. That’s why I wanted that journalist to ask Lynda Korin about it.’ He paused for a moment, considering me. ‘But I’ll tell you this: the footage that plays on the TV set at the end – that’s California.’

‘The section filmed from inside the car?’

‘Yes.’

‘What makes you say that?’

‘At one point, if you study it closely, you can see a slight reflection in the window of the vehicle that the footage is being filmed from. The reflection is of a Cadillac Coupe DeVille – and it’s got blue and yellow Californian licence plates. That was the type of plate they used out there between 1969 and the mid eighties.’

‘So it’s California, but not LA?’

‘It probably

is

LA,’ Walker said, ‘but there’s not really enough to go on, so I can’t be one hundred per cent sure. It’s kind of a best guess.’

‘Do you think Hosterlitz shot the footage himself?’

‘That would be the natural assumption.’

I tried to imagine

when

he might have shot it, and there was really only one possibility: in the time before he left the States in 1970. He couldn’t have recorded it during his trip out to LA in December 1984 because the footage appeared in all eleven films he released in the five years

before that. In theory, at least, he might have been able to do it during his and Korin’s original holiday in Minnesota, during the summer of 1979, but if he’d disappeared for a week, just like he did that Christmas, Wendy surely would have remembered it.

What interested me more than all of that, though, was how Walker knew the films in such detail, right down to the reflections that were visible in windows for fractional periods of time. It suggested he really

had

seen all eleven films, over and over again. It suggested he had access to them. It probably meant they were close by.

He just didn’t trust me enough to show me yet.

I went to my phone and found the photographs I’d taken of the wooden angel pictures, then handed him my mobile.

‘What’s this?’ he asked.

‘Do you recognize the angel?’

He shook his head.

‘It never featured in any of Hosterlitz’s films?’

‘No,’ he said.

‘It belonged to Lynda Korin. Or maybe Hosterlitz himself. Swipe through to the next picture.’

He did as I asked. ‘ “I hope you can forgive me, Lynda.” ’ Walker looked up. ‘Is that Hosterlitz’s handwriting?’

‘I think so. He wrote it on the back of one of the photos.’

‘What is he asking forgiveness for?’

I thought of what Alex had told me in the Portakabin.

Robert Hosterlitz isn’t the man you think he is

.

‘That’s what I need to find out,’ I said.

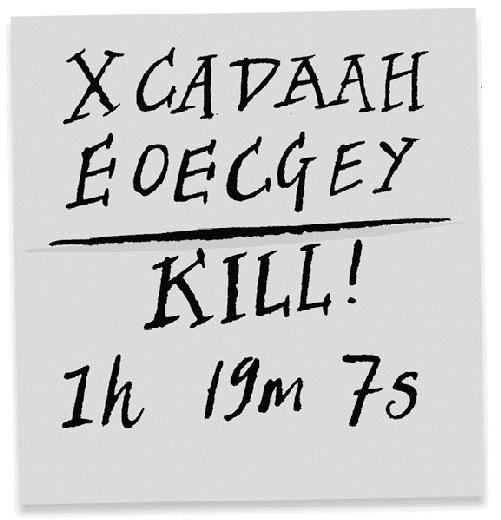

He handed me back the phone, and I went to the picture of the Post-it note I’d discovered at Korin’s house. The original was gone – Egan had burned it while I’d been out at the

scrapyard – but he hadn’t got around to deleting the digital copy from my phone. I needed to figure out what the letters meant, but I also needed to get a fix on the timecode too.

‘Does this mean anything to you?’ I asked, holding up the screen.

Walker leaned in and took the phone again. ‘The two lines of letters? No.’

‘What about under that?’

‘Is that a

Kill!

timecode?’

‘I think so. Do you know what it might be referring to specifically?’

He pressed his lips together. It clearly meant nothing to him, but his eyes continued to switch between me and the phone display, as if he was thinking.

‘No,’ he said after a while.

‘You’ve no idea what the timecode means?’

‘No,’ he repeated. ‘But there might be a way of finding out.’

50

He got up, gestured for me to follow him, and led me into the kitchen. In the corner, out of sight, was a set of five oak drawers.

He pulled at the middle one.

Except they weren’t drawers at all. The whole thing was a single oak panel, made to look like a series of drawers. Immediately inside, filling the entire space, was a dark grey steel safe. It had a number pad on it and a turning wheel.

Walker put in a code.

The safe made a short buzz and then he spun the wheel until the door bumped away from its frame. Wisps of smoke escaped through the gap – and then I realized it wasn’t smoke at all, but tendrils of freezing-cold air.

The safe was a refrigerator.

Inside were two big metal drawers, stacked on top of each other. Each had a handle. Walker grabbed the top one and pulled, and the drawer slid smoothly out from the space it had occupied on a set of runners.

‘These things were originally built to hold six 2,000-foot reels of 35mm film,’ he said, turning to me. He seemed nervous, as if I might be about to push him aside and start tearing into them. ‘They were transportation cases. I bought them in auction – I don’t know, six, seven years ago. At work, we’ve got a vault that stores master material at a constant temperature of minus five, but as I haven’t got one of those and won’t be getting one any time soon, I’ve made do.’

‘You built this yourself?’

‘The cases came as is. Everything else, yes.’

The top case had a latch on its flank, which he flipped, and then he hoisted the lid up. I stepped closer and looked inside. There was a row of five silver film canisters, each one slotted into a moulded foam base, end up. ‘I’ve got all eleven of the films that Robert Hosterlitz made between 1979 and 1984,’ he said. He ran a hand along the canisters. ‘There’s five here and six down there.’

I glanced at the case below.

‘These aren’t the dubbed versions either. They’re the original negatives, in English. The only one of these films you can buy now in English is

Axe Maniac

, and that DVD version is made from a distribution print. Same deal with the other DVD releases that have been dubbed into Spanish and Italian. All are distribution prints, not originals. I know, because I’ve had the original negatives since 1987.’

‘How?’

He pushed the top case in slightly and pulled the bottom one out, opening it to reveal the other six canisters. ‘I was born in Madrid,’ he said. ‘My father was a film projectionist at a cinema in Salamanca that used to show English-language films. My mother was a doctor, so she worked a lot of nights, which meant I usually tagged along with Dad. That was how I fell in love with cinema – and where my interest in Hosterlitz started. I used to watch his movies, even though I must have only been ten or eleven, and every time they showed, my father would try to shield my eyes from them. “These are junk,” he used to say to me. “But his early films, now

they

were good.” Most people watch Hosterlitz’s noirs and work forward, losing interest in his movies after

The Ghost of the Plains

. I started at the end

and worked back – and if anything, it only made me more interested in him.’

Walker looked at me, then down at the canisters again. ‘Mano Águila, the production company Hosterlitz worked for between 1979 and 1984, they didn’t close in ’86 because they weren’t making money. They closed because they

were

. The guy who was running it, Pedro Silva – he owed about seventeen million pesetas in unpaid tax. So when the taxman closed in, he shuttered the premises and fled to Argentina. A couple of months after that, I got inside the Mano Águila building.’

‘You stole these?’

He nodded. ‘They’d just been left there. So I grabbed them, chucked them into the car, and I never mentioned it to anyone. My father was English, although he’d lived in Spain for years, and he used to call petty thieves “toerags”. That’s what I was, I suppose – but I’ve never regretted it.’

He leaned down and removed a canister from the bottom case.

‘This is

Kill!

,’ he said.

There was no writing on the canister, just a number 6 on the side.

Kill!

had been the sixth film that Hosterlitz had made for Pedro Silva.

I looked around the room. ‘Have you got a projector?’

He pointed towards the bedroom and led me there. It was semi-lit, a blind at the window keeping the sun out. Walker opened up all the doors on a row of built-in wardrobes. Filling the space was a huge 35mm projector, facing out at the white wall above Walker’s bed, on the opposite side of the room.

He was projecting across to there.

‘This was my father’s,’ he said, laying a hand briefly on the

machine. ‘It’s the 35mm projector he used at the Royale in Salamanca. They let him keep it when the place went belly up in the early nineties. I took it on after he died.’

A moment of sadness flickered in his face as he talked about his father, and then he held up the canister with

Kill!

in it: ‘The film is made up of six different reels, because all Silva’s movies were shot on “short ends” – the ends of rolls of raw negative stock left over from bigger productions. Because of that, and because I don’t have a platter to make the switch between reels easy, if you want to see the whole thing, start to finish, I’m going to have to load it all in manually, one reel at a time. That means there’ll be five breaks as I do.’

‘How long’s the film?’

‘About eighty-five minutes – and that includes the credits.’

The timecode on the Post-it was one hour and nineteen minutes, which put it very near the end of the movie.

‘Just go straight to the last reel,’ I said.

‘You don’t want to see the whole film?’

I shook my head. ‘Just how it ends.’

51

‘Before 1951,’ Walker was saying, leaning over the projector, ‘the industry standard stock was nitrate.’ He was inching the reel through some sort of roller. ‘

My Evil Heart

and

Connor O’Hare

would have been shot on nitrate. That stuff was lethal. It would catch light at the drop of a hat, go off like a box of fireworks, and it was near impossible to put out. But after 1951, everything was shot on safety stock. That’ll burn – but not like nitrate.’ He paused, struggling with something. ‘This reel is Eastmancolor,’ he said, teeth gritted, still struggling. ‘It’s safety stock, so it won’t go up in flames as easily, but it suffers from something called magenta bias. That means, over time, colours fade, leaving only the red hues, especially if it’s not stored properly.’ Something snapped into place. ‘

Finally

,’ he muttered, and then straightened, wiping his hands against his shirt, trying to rid them of sweat. ‘My point is, I’ve done my best to preserve these, but they’re not pristine.’

‘It’s fine,’ I said. ‘Honestly.’

The projector hummed and then rattled into life, a cone of light erupting from its lens, an image immediately cast on to the far wall. The reel made a soft, familiar chatter as the sprockets fed it through the machine, and I was taken back to my childhood, to the cinema I’d gone to as a boy. There was a pop from the audio and then the film’s sound launched from the speakers.

‘How far in are we?’ I asked Walker.

‘This is the seventy-first minute of eighty-five,’ he said.

As the movie began playing, I set the timer going on my watch so I’d have a rough idea of when we got to seventy-nine minutes, and – impatient now – considered getting Walker to wind the reel on quicker. But then a female actor I instantly recognized as Veronica Mae appeared onscreen, and I held off.

Without the benefit of a decent speaker system, because the audio levels hadn’t been properly balanced at the time of production, and because the acting was so bad, it was sometimes hard to follow the dialogue. Onscreen, Mae was joined by two male actors, even worse performers than her, as they sought shelter in an abandoned shop. I listened hard to their exchange and managed to figure out that they were, predictably, escaping the clutches of a deranged killer who had already killed at least three of their friends. The male actors spoke in awful American accents, and the shop had been set-dressed with an American flag.

Eventually, the killer managed to catch up with them as they tried to find an exit at the back of the shop. Dressed in a long hooded raincoat, he sliced one man’s neck, decapitated the other, then chased Veronica Mae into a large upstairs room filled with storage shelves and bric-a-brac. The film was chaotic and badly lit, and backed by a horrible, screeching soundtrack. When I glanced at my watch, I saw we were sixty seconds away from the seventy-ninth minute.

I took a step closer to the projection on the wall, watching as Mae tried, in vain, to show the terror her character was feeling – and then the camera lurched up to the right to show the killer beside her, knife in his hand. But that was when the twist came: as the hood fell away, the killer was finally revealed – and it wasn’t a man at all. It was a woman.