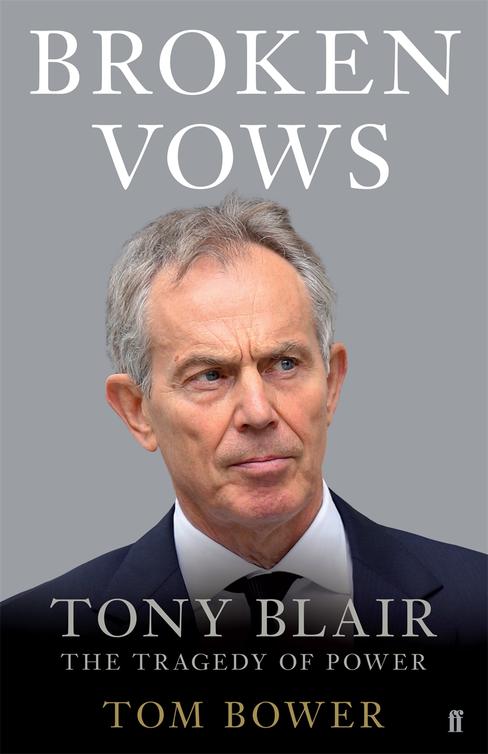

Broken Vows

Authors: Tom Bower

Tony Blair:

The Tragedy of Power

TOM BOWER

To Veronica

- Title Page

- Dedication

- List of Photographs

- Introduction

-

- PART 1: New Labour Takes Charge

- 1: The Beginning

- 2: Uninvited Citizens

- 3: Restoring a Vision

- 4: The Gospel

- 5: Broken Vows, Part 1

- 6: The Battle Plan

- 7: Old King Coal

- 8: The Wall Crumbles

- 9: A Government Adrift

- 10: Frustration

- 11: The War Project

- 12: A Demon to Slaughter

- 13: Saving the NHS

- 14: Everything Is PR

- 15: Clutching at Straws

- 16: Class Conflicts

- 17: Unkind Cuts

- 18: The 2001 Election

-

- PART 2:

A Second Chance - 19: The Same Old Tale

- 20: The Blair ‘Which?’ Project

- 21: Instinct and Belief

- 22: Hither and Dither

- 23: The Bogus Students

- 24: Groundhog Day

- 25: Targets and Dismay

- 26: Broken Vows, Part 2

- 27: Lights Out

- 28: Countdown

- 29: Juggling the Figures

- 30: The Collapse of Baghdad

- 31: Knights and Knaves

- 32: Restoring Tradition

- 33: Lies and Damn’d Lies

- 34: Sabotage and Survival

- 35: Confusion in the Ranks

- 36: Managing the Mess

- 37: The Devil’s Kiss

- 38: Towards a Third Term

-

- PART 3:

‘No Legacy Is So Rich as Honesty’ - 39: Medical Mayhem

- 40: The Legacy Dims

- 41: The Great Game

- 42: The Cost of Confusion

- 43: Cash and Consequences

- 44: Targets vs Markets (Take 8)

- 45: More Heat Than Light

- 46: An Unexpected War

- 47: Self-Destruction

-

- PART 4

:

Redemption and Resurrection - 48: Gun for Hire

- 49: The Tragedy of Power

-

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

- Notes and Sources

- Index

- Photographs

- About the Author

- By the Same Author

- Copyright

The Blairs move into Downing Street, 2 May 1997 (Rebecca Naden/ PA Archive/PA Images)

Blair’s first Cabinet (Rex Shutterstock)

Celebrating the millennium at the Dome on New Year’s Eve 1999 (Rex Shutterstock)

George Bush and Blair at Camp David, 2001 (Mario Tama/AFP/ Getty Images)

Blair and Brown during the 2005 election campaign (Peter Nicholls/ PA Archive/PA Images)

Blair at the Sedgefield election count with Reg Keys (John Giles/PA Archive/PA Images)

Blair, Rupert Murdoch and Wendi Deng (photograph © Hannah Thomson)

Blair at Ariel Sharon’s funeral in Jerusalem, January 2014 (Amos Ben Gershom/GPO via Getty Images)

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers would be pleased to rectify any omissions or errors brought to their notice at the earliest opportunity.

October 2007. Cherie Blair had just telephoned to cancel that evening’s dinner engagement ‘due to an emergency’. She and the African president were due to discuss the creation of a justice ministry in his impoverished country. ‘I understand –’ he began, but was interrupted.

‘I can’t come,’ said Cherie, ‘but Tony says he’d happily join you.’

‘Excellent,’ said Paul Kagame, the ruler of Rwanda, a land-locked nation famous for its gorillas and thousand rolling hills, where 11 million people earn an average daily wage of $2.

Celebrated as the poster boy for British aid to Africa, the president was sitting in the penthouse apartment of a luxury hotel near Chelsea football ground that cost £2,100 per day. He had flown to London in his private jet after addressing the United Nations in New York. His four-day visit matched his celebrity. He would deliver a lecture to Britain’s power brokers at the London School of Economics, then address the Conservative Party conference in Blackpool as David Cameron’s guest, and finally meet Gordon Brown, the new prime minister, in Downing Street. Taking their lead from Tony Blair, all of Kagame’s hosts ignored the fact that their guest was widely accused of being a mass murderer.

Ever since Britain had learned of the horrendous genocide during the early 1990s of 800,000 Rwandan Tutsis by the dominant Hutu tribe, its government had turned a blind eye to the reprisals orchestrated by Kagame, a Tutsi. And now, to the president’s delight, his hero was coming for dinner. Blair arrived, warmly embraced his host and shook hands with David Himbara, a fifty-two-year-old Rwandan economist

personally recruited by the president to rebuild their country’s economy with financial aid from Britain and America.

‘You’re a hero,’ Kagame had told Blair when the first millions of pounds were donated in 1999. ‘You’re the man I’ve been looking for. You’re giving us beautiful pounds to spend as we wish.’

Eight years on, in the penthouse suite, Himbara watched as the president and the world-famous former prime minister bonded in mutual admiration. ‘They charmed each other,’ he would recall. ‘They both said to each other how great the other was.’ Blair felt pride that Kagame’s pledge to transform his country into the ‘Singapore of Africa’ was, thanks to his inspiration, coming true.

The former prime minister, a youthful fifty-four, slim and tanned, set out his stall. ‘I’ve always been interested in you. You are a man with a vision, a leader I’ve always admired. Now you need advisers to show you how to run a government, and I’m your man.’

Blair continued his pitch: ‘I learned by bitter experience during ten years as prime minister the problems of getting the government machine to deliver what I wanted. I created a Delivery Unit, and that was a great success. It transformed everything. I want to bring that success to Africa.’

‘Yes,’ said Kagame repeatedly. He agreed to welcome Blair’s team.

The following day, Himbara arrived at Blair’s new headquarters in Grosvenor Square, which Blair had rented for £550,000 a year following his resignation three months earlier. On the walls of the corridor leading to his office were photographs showing him with world leaders. The overwhelming impression was of entering the presence of a global celebrity. For two hours, Blair explained to Himbara how twelve experts, employed by his new Africa Governance Initiative (AGI), would work inside the president’s office and Rwanda’s economic ministry to improve the government’s effectiveness. Himbara, formerly a professor of economics in South Africa, was relieved that Blair’s experts would be more skilled than the ‘DFID types’ – untalented British civil servants sent after 1999 by Clare Short’s Department for International

Development. But, unlike Blair, Himbara doubted that Kagame would take advice. ‘That evening,’ he recalled a couple of years later, ‘they lied to each other.’

Blair was thrilled by Kagame’s enthusiasm. AGI, his banner programme, had been launched effortlessly. After the frustrations of Downing Street, he intended to modernise Africa and, through his Faith Foundation, heal religious intolerance across the world. Both charities would be financed by his personal income and bequests from the philanthropic billionaires who congregated at the annual World Economic Forum in Davos. Soon after, he solicited annual donations of about £1 million for AGI in Rwanda from David Sainsbury, the former science minister, and Bill Gates.

Within a year of AGI’s launch, Jonathan Reynaga, a former Downing Street aide, arrived in Kigali, the Rwandan capital, to embed himself and his team. By then, Blair had introduced Kagame to the international circuit of leaders’ conferences across America and in Davos. He was presenting the president as Africa’s ‘Mr Clean’; no one mentioned the continuing massacre of Hutus in the neighbouring Congo by militia dispatched by Kagame. Nor did Blair’s audience refer to the systematic theft by Kagame’s armed forces of diamonds, gold and other precious minerals from Congo to finance their lifestyle. After all, the president’s virtues were also hailed by Bill Clinton, Blair’s ally.

The following year, 2008, Blair was welcomed by Himbara at Kigali airport, having stepped off a commercial flight from Nairobi. Like all visitors, he was impressed by Kigali’s clean streets, new skyscrapers, Internet network and stock exchange. Soon he was telling his host how British and American aid was transforming the country into the continent’s showcase. But Himbara knew the truth: the Internet rarely worked because the country lacked electricity, and the stock exchange listed exactly seven corporations – three of which were foreign-owned, with another belonging to the president. The legacy of Belgium’s colonial occupation was a nation of illiterate subsistence farmers lacking the means to build a modern infrastructure. Despite all the millions

in aid, the life of Rwandans outside the capital remained dire. ‘Twelve AGI staff cannot turn around a dysfunctional state,’ Himbara reflected. ‘How do you start in a country where most people can’t spell?’

Blair was more optimistic. As soon as he was ensconced in the presidential palace, his conversation with Kagame centred on him as an experienced leader willing to offer his advice at any time. At the end, Kagame summoned Himbara. ‘Please arrange for Mr Blair to fly back to London on my private jet,’ he ordered. Shortly after, Blair and his staff climbed aboard the $30 million Bombardier BD-700 ‘Global Express’ to fly non-stop to Stansted. The cost of the round-trip flight – about $400,000 – was billed to the Rwandan government.

A year later, Blair returned to Kigali, again on the president’s jet. Conditions were not as impressive as they had been on his last visit. Kagame feared the outcome of the upcoming elections but, since Blair paraded him as a model of African democracy, they could not be cancelled. Although there was no meaningful opposition party and Kagame was guaranteed over 90 per cent of the vote, his paranoia was causing fatal repercussions. Any journalist or businessman who was critical of the government was beaten up; his personal doctor had been murdered. A UN investigation into Kagame’s attacks against the Hutus in the Congo during the 1990s was due to report that the president was guilty of genocide.

Suspicious of any independent-minded Rwandan, Kagame forbade Himbara to spend time alone with Blair during his visit. Himbara carefully obeyed the orders until he bid Blair farewell outside the president’s palace. ‘Jump in and come with me,’ Blair ordered, pulling Himbara into the limousine. ‘I’m a dead man,’ thought Himbara, as Blair asked him to recite his fears. By the end of their journey to the airport, Blair had heard that ‘It’s getting nasty here. People are disappearing.’ He did not comment. Once again, he boarded the president’s jet and flew towards Europe.

At Christmas, Himbara joined his family in Johannesburg. Fearing for his life, he did not return to his country. Even in South Africa he

wasn’t safe. Another Rwandan exile, a personal friend living near by, was murdered by a hit squad. Although Kagame duly won the 2010 election with 93 per cent of the vote, the leaders of the small opposition party were being hunted down. Their beheaded corpses, hacked by machetes, were strewn about the countryside.

Blair ignored those events. Instead, he hailed his protégé’s success. ‘The popular mandate received by President Kagame in the recent presidential election is a testament to the huge strides made under his formidable leadership,’ he said. In Britain, police in London announced that a plot hatched in Kigali to murder two Rwandan exiles had been foiled.

In 2012, Himbara heard that Tony Blair would be addressing an ‘Executive Leadership Conference’ in Johannesburg. He paid $450 for a ticket and sat in the front row. At question time, he raised his hand. ‘How is your Rwandan project going?’ he asked Blair. ‘I had to run for my life. But, for you, it’s business as usual. Why?’

‘Oh, David,’ replied Blair, ‘Good to see you, man. Next question.’

At the end of the session, Blair walked out, avoiding Himbara’s gaze. Five years after leaving Downing Street, he was accountable to no one. He had bidden good riddance to Parliament, civil servants and the Labour Party. Democracy, he had decided, hindered effective government. Casualties like David Himbara were not his concern.

Two years later, in 2014, after several more trips to Kigali and meetings with Kagame at Davos and elsewhere, Blair was sent a report by the US Department of State describing the murderous oppression in Rwanda. Again, he said nothing. The following year, he was equally silent after Congressional hearings in Washington denounced the murders of Kagame’s opponents.

Three months on, in June 2015, one of Kagame’s associates, General Karenzi Karake, the head of Rwanda’s intelligence service, arrived at Heathrow on an official visit. To his surprise, he was arrested on an international warrant for ‘war crimes against civilians’ issued in Spain. He was immediately imprisoned. To resist his extradition to Spain, he hired Cherie Blair. In defence of her client, she told the magistrate that

the general was ‘a hero in Rwanda and they very much want him home as soon as possible’. Karake was released on bail of £1 million. Two months later, he was freed on a legal technicality before the charges were heard, and flew back home. Kagame’s opponents were shocked. Cherie, like her husband, was hailed by Kagame as a hero.

*

Since his resignation in June 2007, Tony Blair’s relations with dictators have been, and continue to be, bewildering. The defining events of his ten years as prime minister were the humiliation of Slobodan Milošević, the Serbian dictator, and the toppling of Iraqi president Saddam Hussein. In the cause of democracy, Blair defiantly risked his office to remove leaders he repeatedly described as evil. Set free from government, a different Tony Blair emerged from the politician who had spoken on behalf of New Labour. Eleven years after risking his reputation to topple Saddam, he publicly justified strong, authoritarian government. ‘You also need efficacy,’ he wrote in the

New York

Times

. ‘You need effective government taking effective decisions.’ He recalled that in 2001 the British army and not Whitehall’s civil servants had solved the foot-and-mouth epidemic that ravaged the nation’s cattle. Soldiers and corporate chief executives rather than democratically elected representatives are, he argued, the best managers.

Since he left Downing Street, the accusations against Blair have grown. The image of a career carefully balanced between global charity and his commercial consultancies has become frayed. Despite his efforts to remain invisible, regular reports have described a global traveller jetting between Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Europe and America to earn millions of pounds by offering advice to sheikhs, presidents and dictators.

His new pitch, refined since his first meeting with Kagame, was perfectly delivered on 13 May 2015 to President Buhari of Nigeria. After his arrival at Abuja airport on a jet chartered by Evgeny Lebedev, the son of the former KGB colonel who owned the London

Evening Standard

, Blair was whisked to the Hilton Hotel. Besides Lebedev, his entourage included Nick Thompson, the head of the AGI, his police protection

officer and a personal assistant. The following morning, he called on Andrew Pocock, the British High Commissioner. The routine was familiar. In every country he visits, Blair expects the British embassy to provide a comprehensive security briefing. In Nigeria, he was especially interested in the threat posed by Boko Haram, the Islamic terror group murdering hundreds of civilians in the north of the country. Armed with classified information, he then sped in a motor cavalcade to the office of Muhammadu Buhari, recently elected as president and committed to ridding his country of endemic corruption. Getting access to the new president even before his inauguration was a notable achievement. Blair’s reputation overcame many hurdles.

In their first meeting, Blair introduced himself as ‘Britain’s most successful prime minister’. With the benefit of age, experience and hindsight, he explained to Buhari, he had learned how to focus on important matters and work the system. ‘I pioneered the skills to make government work effectively,’ he told the president. ‘The Delivery Unit is the leader’s weapon to make his government effective across the civil service and country.’ He offered Buhari the benefit of that expertise. AGI would establish a delivery unit within his government, with paid staff.

Buhari, a former army general who had orchestrated a successful coup in 1983, looked bored. The wizened politician, famous for imprisoning his opponents without trial until he was deposed in a counter-coup and jailed for three years, stared intently at Lebedev. The Russian seemed equally uninterested in Blair’s sermon. Buhari’s assistant had earlier asked why Lebedev was included in the meeting. ‘It’s his plane,’ replied a member of Blair’s staff, ‘and he’s interested in Blair’s work against Ebola in Sierra Leone.’

‘Could you all leave us alone now?’ Blair announced. ‘I have a personal message for the president from David Cameron.’ Twenty minutes later, the two men emerged. Buhari was noticeably disgruntled. Blair, he told an aide, had used his access to tout for business on behalf of Tony Blair Associates, his commercial calling card. He had offered the sale of Israeli drones and other military equipment to help defeat

the Islamic uprising. ‘Blair is just after business,’ muttered Buhari.