Bruno's Dream (36 page)

Authors: Iris Murdoch

Miles’s indignation had been extreme and comic. Her perception of the comicality of Miles in this situation had been one of the things which had helped Diana herself to bear it. It had been some time before Miles would even believe what Diana was telling him. He regarded it as

impossible,

as

strictly contradictory.

He stared at Diana with wild amazed eyes. It was all a

mistake

, she would find that she had been mistaken, she had certainly got it wrong. For nature so preposterously to err … When at last Diana did succeed in persuading Miles of the truth of what she said, that Lisa was not leading a dedicated life in India but was to be seen riding about London in Danby’s new sports car and dining with Danby at riverside restaurants, dressed in extremely smart new clothes, Miles gave himself up to a day of rage and execration. He cursed Danby, he cursed Lisa. He said it could not possibly last. She would be sorry, my God, she would be sorry! He announced himself irreparably damaged. The next day he was silent, frowning, concentrating, refusing to answer Diana’s questions. On the third day he said to Diana enigmatically, ‘It’s all over now,’ and returned to work in the summer house. It was another week before Diana, walking down the garden, saw once more the strange angelic smile upon his face as he wrote.

Lisa had sent no communication to Miles and offered no explanation to Diana. Diana had simply discovered her with Danby one morning at Stadium Street. They had assumed that she would immediately understand. They looked upon her golden-eyed, a little apologetically, coaxingly like children. And, as it seemed to Diana, almost at once started treating her as if she were their mother. It had taken Diana herself some time to see and to believe what was there in front of her face. It had been a very bitter revelation. Diana, when she had first taken it on herself to visit Bruno regularly, had come to find a certain sweetness in her renewed relationship with Danby. She felt she had not really got over him and saw no reason why she should try to. She experienced his attractiveness now in a more diffused and peaceful way as a comforting warmth and a consoling presence. There was healing for her in their coexistence with Bruno. She could see that Danby was unhappy. She respected his grief and looked forward to a time when she might be able in turn to console him. She felt vague about this. There would be no extremes. But something would have survived the wreck. When poor Bruno is dead, she thought, I’ll consider about Danby and I’ll see what to do. In fact, she thought a lot about him, especially in the evenings when she was alone in the drawing room at Kempsford Gardens, and his image brought her a kind of happiness.

But now. Lisa had taken Miles away from her and now she had taken Danby too. While she listened to Miles’s outraged cries she struggled with her own pain. How could her resentment ever have an end? She realised now just how much she had been relying on Danby. Indeed it was not until Miles told her that at least she ought to be pleased by this definitive removal of her rival that this aspect of the matter occurred to her at all. Danby was far more final than India. A Lisa in India would have become a divinity. A Lisa sitting in Danby’s car with an arm outstretched along the back of the seat, as Diana had last seen her, was fallen indeed. Miles said venomously, ‘Well, she had chosen the world and the flesh. Let’s hope for her sake she doesn’t find she’s got the devil as well!’ Naturally it did not occur to Miles that Diana would be other than pleased. In fact, he was not concerned with Diana’s feelings, being so absorbingly interested in his own. He will manage, she thought, he will manage. We’ve all paired off really, in the end. Miles has got his muse, Lisa has got Danby. And I’ve got Bruno. Who would have thought it would work out like that?

Diana felt that she had emerged at last into a vast place of loneliness. Danby and Lisa, with their solicitous concern about her and their submissive politeness, were as lost to her as if they were dead. And she was beginning to realise how little Miles really reflected about her, how little he tried in his imagination to body forth the real being of his wife. His imagination was engaged in other and more exotic battles. He had seemed very close to her when he had talked to her about Parvati, but it seemed to her now that she had simply been made use of. Miles had needed a crisis in his relations with the past, he had needed a certain ordeal, and she had helped him to achieve it. Now he had returned into himself more self-sufficiently than ever before. She thought of startling him into noticing her by telling him that she too was in love with Danby. But that would be merely to add absurdity to pain.

And now, she thought, I have done the most foolish thing of all, in becoming so attached to someone who is dying. Is this not the most pointless of all loves? Like loving death itself. The tending of Bruno had had at first simply a kind of consoling inevitability. It was something compulsory, a task, a duty, and it took her away from Kempsford Gardens where Miles sat smiling his entranced and private smile. It also brought her into a natural relationship with Danby. Later Danby’s proximity was a torment. But by then she had come to love Bruno, to love him with a blank unanxious hopeless love. He could give her nothing in return except pain. And it seemed to her as the days went by and Bruno became weaker and less rational, that she had come to participate in his death, that she was experiencing it too.

Diana felt herself growing older and one day when she looked in the glass she saw that she resembled somebody. She resembled Lisa as Lisa used to be. Then she began to notice that everything was looking different. The smarting bitterness was gone. Instead there was a more august and terrible pain than she had ever known before. As she sat day after day holding Bruno’s gaunt blotched hand in her own she puzzled over the pain and what it was and where it was, whether in her or in Bruno. And she saw the ivy leaves and the puckered door knob, and the tear in the pocket of Bruno’s old dressing gown with a clarity and a closeness which she had never experienced before. The familiar roads between Kempsford Gardens and Stadium Street seemed like those of an unknown city, so many were the new things which she now began to notice in them: potted plants in windows, irregular stains upon walls, moist green moss between paving stones. Even little piles of dust and screwed up paper drifted into corners seemed to claim and deserve her attention. And the faces of passersby glowed with an uncanny clarity, as if her specious present had been lengthened out to allow of contemplation within the space of a second. Diana wondered what it meant. She wondered if Bruno was experiencing it too. She would have liked to ask him, only he seemed so far away now, wrapped in a puzzlement and a contemplation of his own. So they sat together hand in hand and thought their own thoughts.

The pain increased until Diana did not even know whether it was pain any more, and she wondered if she would be utterly changed by it or whether she would return into her ordinary being and forget what it had been like in those last days with Bruno. She felt that if she could only remember it she would be changed. But in what way? And what was there to remember? What was there that seemed so important, something that she could understand now and which she so much feared to lose? She could not wish to suffer like this throughout the rest of her life.

She tried to think about herself but there seemed to be nothing there. Things can’t matter very much, she thought, because one isn’t anything. Yet one loves people, this matters. Perhaps this great pain was just her profitless love for Bruno. One isn’t anything, and yet one loves people. How could that be? Her resentment against Miles, against Lisa, against Danby had utterly gone away. They will flourish and you will watch them kindly as if you were watching children. Who had said that to her? Perhaps no one had said it except some spirit in her own thoughts. Relax. Let them walk on you. Love them. Let love like a huge vault open out overhead. The helplessness of human stuff in the grip of death was something which Diana felt now in her own body. She lived the reality of death and felt herself made nothing by it and denuded of desire. Yet love still existed and it was the only thing that existed.

The old spotted hand that was holding on to hers relaxed gently at last.

Iris Murdoch (1919–1999) was one of the most influential British writers of the twentieth century. She wrote twenty-six novels over forty years, as well as plays, poetry, and works of philosophy. Heavily influenced by existentialist and moral philosophy, Murdoch’s novels were also notable for their rich characters, intellectual depth, and handling of controversial topics such as adultery and incest.

Born in Dublin, Ireland, Murdoch moved to London with her parents as a child. She attended Somerville College in Oxford where she studied classics, ancient history, and philosophy. While at Oxford, she was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (which she later left, disillusioned) and, in the 1940s, worked in Austrian and Belgian relief camps for the United Nations. After completing her postgraduate degree at Newnham College in Cambridge, she became a Fellow of St. Anne’s College, Oxford, where she lectured in philosophy for fifteen years.

In 1954, she published her first novel,

Under the Net

, about a struggling young writer in London, which the American Modern Library would later select as one of the one hundred best English-language novels of the twentieth century and

Time

magazine would list as among the twenty-five best novels since 1923. Two years after completing

Under the Net

, Murdoch married John Bayley, an English scholar at the University of Oxford and an author. In a 1994 interview, Murdoch described her relationship with Bayley as “the most important thing in my life.” Bayley’s memoir about their relationship,

Elegy for Iris

, was made into the major motion picture

Iris

, starring Judi Dench and Kate Winslet, in 2001.

For three decades, Murdoch published a new book almost every year, including historical fiction such as

The Red and the Green

, about the Easter Rebellion in 1916, and the philosophical play

Acastos: Two Platonic Dialogues

. She was awarded the 1978 Booker Prize for

The Sea, The Sea

, won the Royal Society Literary Award in 1987, and was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1987 by Queen Elizabeth.

Her final years were clouded by a long struggle with Alzheimer’s before her passing in 1999.

Murdoch as an infant with her mother, Irene, in 1919. Irene was a trained opera singer, though she gave it up after Iris was born. Murdoch’s father, John, worked as a civil servant once the family moved to London.

Murdoch in 1923, at age three or four. She was an only child and remembered her childhood as “a perfect trinity of love.” Her father encouraged her to read at a young age and her favorite authors included Lewis Carroll and Robert Louis Stevenson.

The London house in which Murdoch grew up, seen here in 1926.

Murdoch in 1935. She was studying philosophy, classics, and ancient history at Oxford at the time of this photo.

Murdoch with an unidentified friend in 1946. At this time Murdoch was studying philosophy at Cambridge, where she enrolled after working for the United Nations to help Europeans displaced by the Second World War.

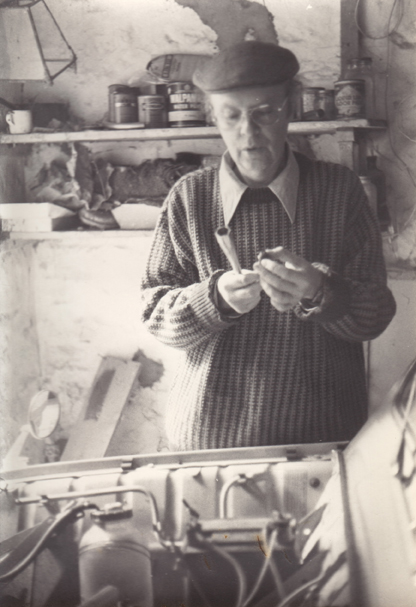

John Bayley, Murdoch’s husband, in the 1960s. The two were married in 1956 after meeting at Oxford.

Murdoch and Bayley at an unknown date. One of the couple’s shared passions was swimming, which they did together whenever the opportunity presented itself.

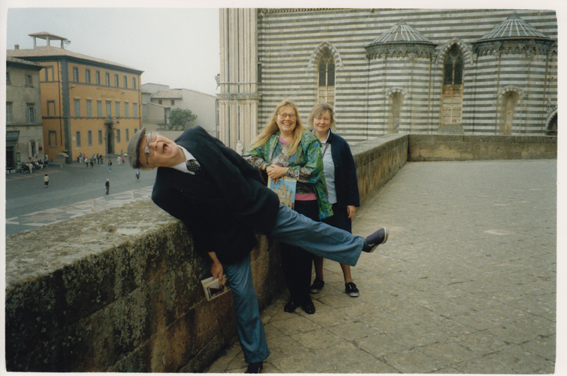

Bayley and Murdoch on vacation in Orvieto, Italy, in September 1988, with family friend Audi Villers, whom Bayley married after Murdoch’s death.

Bayley and Murdoch in Delft, Holland, in 1996. Murdoch was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in the mid-1990s.

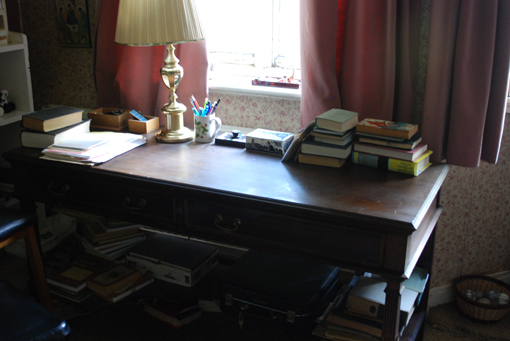

Bayley’s writing desk, which originally belonged to J.R.R. Tolkien. Murdoch’s scrapbook can be seen atop the desk.