Brutal Women (8 page)

Authors: Kameron Hurley

“You’re telling me a beautiful

painter says you’re the love of their life and you blow them off? You’re

stupider than Margin gives you credit for.”

We were, of course, at the

Madhattered. Page and Nib were male and female, respectively, arguing about

whether or not Nib looked better in Page’s tutu than Page did, which

technically wasn’t an appropriately gender-prescribed discussion. Margin was

flirting with someone named after a kitchen appliance. Rule was drinking tarls.

“I’ll never understand what a

bright person like Sunshine sees in you,” Rule said. “You can be mewling. A

lazy coward, when the mood suits you. Sunshine needs fire. Someone whose

thinking works outside the perpetual.”

I glanced over at Page and Nib and

Margin. “You think any of us is ever going to be perpetual?”

“No, Cue. I think we’re the lost

children of history. Perpetually adolescent.”

Sunshine remained male for almost

four months: four seasons, half the year. He spent his nights in his studio. He

locked it whenever he left.

I received my government contract

for the year, a detailed itinerary of little towns on the outskirts of the

northern province, most of which hadn’t been photographed in almost a decade. I

told Sunshine that I’d be leaving the next day. He said nothing. Something was

slipping away.

The day I left, Sunshine walked me

to the silver tube of the train.

“When you get back my project will

be done,” he said.

I nodded. I was female that day.

The first town on my itinerary was Lilac, a last resting place for female

queers. I wasn’t allowed to photograph the town, of course, because queers

can’t legally formulate a self-willed gendered identity—and are therefore

outside the realm of history. I was only going there to take a written census

for the health authority.

“I’ve been thinking about being a

couple,” I said.

Sunshine glanced up at me.

“When I come back I can be

perpetually female,” I said, “and you can be perpetually male. We’ll sign the

government forms for—”

Sunshine put his finger to my lips.

“You don’t understand, Cue.” He kissed me. He left me.

I called Sunshine every night, but

the operator could never get a connection through. “No one’s picking up the

receiver,” the operator said.

I photographed four women in

Evergreen and thirty-two men in Beech. In Coriander, a bridge washed out, and

eight men and twelve women died before I could photograph them, erasing them

from history forever. I met three men named Stove who took me out for tarls and

toast. I slept with a woman named Cup after I photographed her nude, surrounded

by her twelve perpetually sexed children.

“It’s so good to see them all as

real people,” she told me.

I went by mule and rickshaw and

carriage and steam car. A town named Magnolia, a blond woman named Comb. A stir

of queer men outside a pub in Fern being given handouts and then beaten away

with sticks. Mothers now perpetually male, fathers now perpetually female.

Neuter children plucking at my imager, tugging at my sleeves. The black, lined

face of a person named Ripple whose sex I never knew, because all I saw was the

face and hands, gesturing for the imager through the folds of a black robe.

Eighteen women in Hyacinth wearing crimson headbands. Two nude men in Willow

with bodies lean and sinewy as whips. A man named Rubble. A woman named Stone.

When I got back to the train line

it was already low autumn, and as the train curled toward the city, the rain

started, slow and steady, streaming past my windowpane in ever-changing

rivulets. Different patterns, different paths, but always rain.

I climbed the stairs to the flat

Sunshine and I shared, but there were no lights on. I unlocked the door and

palmed on the light.

Sunshine’s paintings were gone. All

of Sunshine’s things were gone. I walked slowly through the flat, the living

space, our bedroom. Her books were gone, his black suits, her red tutu, the

silver scarf I gave him for her birthday. I turned on the light in the studio.

The room was bare. The floor had been scraped clean. White walls, white floor,

an empty room looking out onto the cloud-heavy bay.

I stood in the doorway, numb.

The phone rang.

I dropped my traveling case and ran

to the living area, picked up the receiver.

“Connected,” the operator said.

“Sunshine!” I cried.

“Fuck, no! Why aren’t you here?”

Rule said.

“What?”

Margin’s voice crackled in through

another line. “Sunshine’s opening is tonight! Why aren’t you here? He told you,

didn’t she?”

“Where?” I said.

“Where else, fool, the

Madhattered,” Rule said. “Get over here. You’re missing it!”

“I’m coming,” I said, and dropped

the receiver. The operator yelled at me. I darted down the stairs.

The Madhattered was crowded, more

crowded than it had ever been. Adolescents and perpetuals vied for space. Three

extra bartenders tossed drinks. Margin wore a black tunic and four-inch green

heels.

Rule dressed in a snazzy suit with

a blue kerchief. Page wore a silver tutu. Nib wore a gold tunic and thigh-high

boots. I hadn’t had time to dress up. I wasn’t even sure what sex I was.

“Where is she?” I asked.

Rule pulled me up to the table.

Page and Nib and Margin all leaned in. Rule pointed to the open gallery doors

by the bar. “We’ve been in. You have to see it, Cue. This is a good crowd, but

it won’t last.”

“Why not? What’s wrong?” I asked.

“Go,” Margin said.

I pushed my way to the gallery,

through the mass of tutus and tunics. In the first room were half a dozen of

Sunshine’s paintings, all of which I’d already seen, in one form or another.

Sunshine wasn’t there. The second gallery, behind the first, was more crowded,

and more people were talking in there, a low rumble of voices. I squeezed my

way past the crowd. Someone elbowed me. A drink spilled across the front of my

blouse. There was only one work in there, made up of seven canvases. A little

rope cordoned it off from the press of people. I was forced up against the

rope. I gazed at the paintings, only— they weren’t really paintings.

They had begun as photographs.

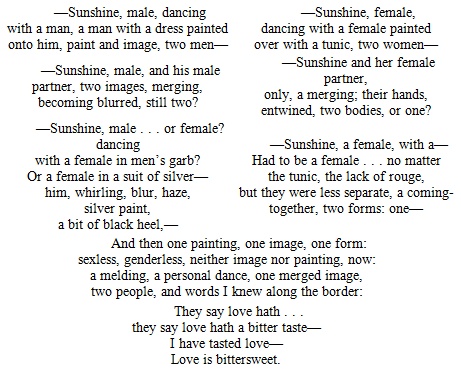

Seven canvases. Sunshine and a faceless partner. But when Sunshine added paint,

they merged into something else.

I saw seven paintings arranged

vertically along the far wall, two-by-two, progressing closer to one another as

they moved inward to frame the final painting mounted below them. The images

were of Sunshine, altered photographs of Sunshine’s unmistakable form:

That final image, that blended

image, I realized, was Sunshine, dancing. Just Sunshine; not male, not female,

just the person I loved, sexless, genderless, Liquid Sunshine, painting

Sunshine’s past, present, future.

Sunshine had created Sunshine,

carved a history of this one image, this one self. No imagers, no

photographers. Just Sunshine, painting over the image that photographers like

me would have set down as truth. Remaking it.

I stared. For how long I stared I

don’t know. At some point I realized my cheeks were wet. I wiped at my face. My

tears.

A hand on my shoulder.

I turned.

Sunshine smiled. “You like it?” she

asked.

I couldn’t say anything.

“You understand,” she said.

I understood. I remembered the

little villages, the rain on the train window. I remembered Ripple beckoning to

me in black robes. Margin and Page, Nib and Rule. My friends, always changing,

cyclical, like the seasons, always the same.

“I wouldn’t have taken those

photographs you altered,” I said.

“I know,” she said. “I still love

you for it.”

She smiled again. Turned. The stir

of people pulled her away.

I could have reached for her. My

fingers and hers, twining together, a merging, too late, of two bodies, two

people, just us, not perpetual, not sexed, just people.

But I did not reach out. I wanted

to watch her go, a ripple through the wave of bodies; there, then lost, adrift

and then swallowed.

I went back to the flat. I sat down

on the floor of the empty studio and cried.

Liquid Sunshine—I always thought of

the piece that way—drew attention from government authorities and moral

purists. Rule told me three months later that Sunshine had disappeared after an

exhibition in a neighboring city, Lavender.

I sat up for three nights wondering

if it would have been different if I had reached out for Sunshine’s hand that

night, if I had told Sunshine that, I, too am infinitely malleable, that I,

too, am capable of painting my own past and future, creating my own image. But

I would have been lying to the one person I loved. And to myself.

Rule and Margin became a perpetual

couple. Margin bore three children. Page and Nib never settled, and were lost

to history. I have no images of Sunshine but memory. They are fewer and fewer

these days, often mixed with more recent faces, freckled women in purple tutus

in Flower, a blond man in Lotus named Glass, three brown neuter children in

Wisteria with paint-stained fingers. I signed a permanent government contract.

I don’t come back to the city much. I don’t like to. It reminds me of my

adolescence. I am perpetually female now, and every year I ask for assignments

further afield, census trips to remote queer villages. I ask for them because

sometimes I think that the farther I go from the city, the farther I will get

from Sunshine . . . the farther I will get from myself.

I longed to create my own perpetual

identity for so long that I never stopped to think that perhaps I would not

like it when I discovered it. Sunshine was right: we all stay the same, there,

in that place that is ourselves, the blending point of sexed identity, gendered

existence, infinitely malleable. Sunshine knew that you could find that place

where the malleable was your view of the world, your view of yourself, but I

never found that. Maybe I don’t believe in it. But Sunshine did. Sunshine

believed in everything.

Even me.

So let’s say Macbeth was a

post-apocalyptic warlord called Madden, and his right-hand man was a woman

named Banan instead of Banquo? Still with me? Good. This one first showed up in

a now defunct online magazine called

The Boundless Realm

back in 1998.

It was the second fiction piece I ever published, and I got a whopping $5 for

it. It’s the original Brutal Women story, and sorta set the scene for

everything I’d write afterward.

I gave birth to my boy along a

barren stretch of the High Way near the King’s hold in Skall, twelve miles from

the Hold at Inveress. I squatted in a dusty ditch as twilight neared, a time

when spirits of the dead and dying roam free in search of unwilling hosts.

I pulled on my tattered trousers -

patched and bloodied so many times that I’ve lost track of which blood came

from whom - and started my walk to Inveress with my son wrapped up in an old

black tarp and bits of burlap. I would train him as I wished, I decided, with

help from the best teacher of battle and survival I knew.

The hold at Inveress is not like

the King’s hold in Skall. It is not one of the old, burned out structures,

built before the cataclysm when men loved their buildings tall and full of

large windows. Inveress was built to defend. It resides on a rocky rise called

Dunsinane Hill, about four miles from the black square of Birnam Glen.

The gate’s small peeking portal

swung inward, and a pair of sharp, frightened blue eyes peered out at me. My

boy sucked contentedly at my breast, wrapped up securely within the tarp. Warm

and fed, he kept silent.

The eyes continued to stare. For a

brief moment, I thought perhaps my greeter had been stabbed in the back; his

eyes remained so emotionless and still in their glistening. As I reached across

my boy for my blade, the man croaked, “Mistress...?” as if it were a question.

And, I suppose, it was. I did not look myself. Women do not carry babes at

their breast.

“Come now, get me your Master, the

Thane of Glen,” I said. “He will not be pleased to know that his comrade Banan

has been kept waiting.”

The peeping portal snapped shut.

The gate opened abruptly, and I

almost dropped my boy for my blade.

“Banan!” the figure cried. It was a

voice deep and familiar. I had to dart from the doorway to keep the man from

crushing my child in his embrace.

“Clumsy, drunken brute,” I growled.

The bright gleam - enhanced by much

drink - in his eyes faded, and he looked down at me from beneath thick,

furrowed brows. A hand strayed to his sword hilt, and I watched his form grow

wary and alert.

“I will ask only one favor of you

in this lifetime,” I said. “I want you to train my boy. Here, in Inveress. I

cannot raise a boy and command battles. You have servants and a Lady. I do

not.”