Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (43 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

26. Two Moon, chief of the Cheyennes. Courtesy of Denver Public Library.

27. Hump, photographed at Fort Bennett, South Dakota, in 1890. Photo from the National Archives.

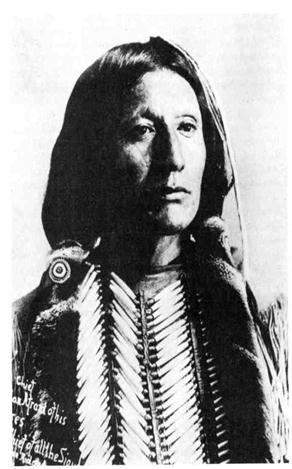

28. Crow King of the Sioux. Courtesy of Denver Public Library.

“The smoke of the shooting and the dust of the horses shut out the hill,” Pte-San-Waste-Win said, “and the soldiers fired many shots, but the Sioux shot straight and the soldiers fell dead. The women crossed the river after the men of our village, and when we came to the hill there were no soldiers living and Long Hair lay dead among the rest. … The blood of the people was hot and their hearts bad, and they took no prisoners that day.”

29

Crow King said that all the soldiers dismounted when the Indians surrounded them. “They tried to hold on to their horses, but as we pressed closer they let go their horses. We crowded them toward our main camp and killed them all. They kept in order and fought like brave warriors as long as they had a man left.”

30

According to Red Horse, toward the end of the fighting with Custer, “these soldiers became foolish, many throwing away their guns and raising their hands, saying, ‘Sioux, pity us; take us prisoners.’ The Sioux did not take a single soldier prisoner, but killed all of them; none were alive for even a few minutes.”

31

Long after the battle, White Bull of the Minneconjous drew four pictographs showing himself grappling with and killing a soldier identified as Custer. Among others who claimed to have killed Custer were Rain-in-the-Face, Flat Hip, and Brave Bear. Red Horse said that an unidentified Santee warrior killed Custer. Most Indians who told of the battle said they never saw Custer and did not know who killed him. “We did not know till the fight was over that he was the white chief,” Low Dog said.

32

In an interview given in Canada a year after the battle, Sitting Bull said that he never saw Custer, but that other Indians had seen and recognized him just before he was killed. “He did not wear his long hair as he used to wear it,” Sitting Bull said.

“It was short, but it was the color of the grass when the frost comes. … Where the last stand was made, the Long Hair stood like a sheaf of corn with all the ears fallen around him.”

33

But Sitting Bull did not say who killed Custer.

An Arapaho warrior who was riding with the Cheyennes said that Custer was killed by several Indians. “He was dressed in buckskin, coat and pants, and was on his hands and knees. He had been shot through the side, and there was blood coming from his mouth. He seemed to be watching the Indians moving around him. Four soldiers were sitting up around him, but they were all badly wounded. All the other soldiers were down. Then the Indians closed in around him, and I did not see any more.”

34

Regardless of who had killed him, the Long Hair who made the Thieves’ Road into the Black Hills was dead with all his men. Reno’s soldiers, however, reinforced by those of Major Frederick Benteen, were dug in on a hill farther down the river. The Indians surrounded the hill completely and watched the soldiers through the night, and next morning started fighting them again. During the day, scouts sent out by the chiefs came back with warnings of many more soldiers marching in the direction of the Little Bighorn.

After a council it was decided to break camp. The warriors had expended most of their ammunition, and they knew it would be foolish to try to fight so many soldiers with bows and arrows. The women were told to begin packing, and before sunset they started up the valley toward the Bighorn Mountains, the tribes separating along the way and taking different directions.

When the white men in the East heard of the Long Hair’s defeat, they called it a massacre and went crazy with anger. They wanted to punish all the Indians in the West. Because they could not punish Sitting Bull and the war chiefs, the Great Council in Washington decided to punish the Indians they could find—those who remained on the reservations and had taken no part in the fighting.

On July 22 the Great Warrior Sherman received authority to assume military control of all reservations in the Sioux country and to treat the Indians there as prisoners of war. On August 15 the Great Council made a new law requiring the Indians to give

up all rights to the Powder River country and the Black Hills. They did this without regard to the treaty of 1868, maintaining that the Indians had violated the treaty by going to war with the United States. This was difficult for the reservation Indians to understand, because they had not attacked United States soldiers, nor had Sitting Bull’s followers attacked them until Custer sent Reno charging through the Sioux villages.

To keep the reservation Indians peaceful, the Great Father sent out a new commission in September to cajole and threaten the chiefs and secure their signatures to legal documents transferring the immeasurable wealth of the Black Hills to white ownership. Several members of this commission were old hands at stealing Indian lands, notably Newton Edmunds, Bishop Henry Whipple, and the Reverend Samuel D. Hinman. At the Red Cloud agency, Bishop Whipple opened the proceedings with a prayer, and then Chairman George Manypenny read the conditions laid down by Congress. Because these conditions were stated in the usual obfuscated language of lawmakers, Bishop Whipple attempted to explain them in phrases which could be used by the interpreters.

“My heart has for many years been very warm toward the red man. We came here to bring a message to you from your Great Father, and there are certain things we have given to you in his exact words. We cannot alter them even to the scratch of a pen. … When the Great Council made the appropriation this year to continue your supplies they made certain provisions, three in number, and unless they were complied with no more appropriations would be made by Congress. Those three provisions are: First, that you shall give up the Black Hills country and the country to the north; second, that you shall receive your rations on the Missouri River; and third, that the Great Father shall be permitted to locate three roads from the Missouri River across the reservation to that new country where the Black Hills are. … The Great Father said that his heart was full of tenderness for his red children, and he selected this commission of friends of the Indians that they might devise a plan, as he directed them, in order that the Indian nations might be saved, and that instead of growing smaller and smaller until

the last Indian looks upon his own grave, they might become as the white man has become, a great and powerful people.”

35

To Bishop Whipple’s listeners, this seemed a strange way indeed to save the Indian nations, taking away their Black Hills and hunting grounds, and moving them far away to the Missouri River. Most of the chiefs knew that it was already too late to save the Black Hills, but they protested strongly against having their reservations moved to the Missouri. “I think if my people should move there,” Red Cloud said, “they would all be destroyed. There are a great many bad men there and bad whiskey; therefore I don’t want to go there.”

36

No Heart said that white men had already ruined the Missouri River country so that Indians could not live there. “You travel up and down the Missouri River and you do not see any timber,” he declared. “You have probably seen where lots of it has been, and the Great Father’s people have destroyed it.”

“It is only six years since we came to live on this stream where we are living now,” Red Dog said, “and nothing that has been promised us has been done.” Another chief remembered that since the Great Father promised them that they would never be moved they had been moved five times. “I think you had better put the Indians on wheels,” he said sardonically, “and you can run them about whenever you wish.”

Spotted Tail accused the government and the commissioners of betraying the Indians, of broken promises and false words. “This war did not spring up here in our land; this war was brought upon us by the children of the Great Father who came to take our land from us without price, and who, in our land, do a great many evil things. … This war has come from robbery—from the stealing of our land.”

37

As for moving to the Missouri, Spotted Tail was utterly opposed, and he told the commissioners he would not sign away the Black Hills until he could go to Washington and talk to the Great Father.

The commissioners gave the Indians a week to discuss the terms among themselves, and it soon became evident that they were not going to sign anything. The chiefs pointed out that the treaty of 1868 required the signatures of three-fourths of the male adults of the Sioux tribes to change anything in it, and

more than half of the warriors were in the north with Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. In reply to this the commissioners explained that the Indians off the reservations were hostiles; only friendly Indians were covered by the treaty. Most of the chiefs did not accept this. To break down their opposition, the commissioners dropped strong hints that unless they signed, the Great Council in its anger would cut off all rations immediately, would remove them to the Indian Territory in the south, and the Army would take all their guns and horses.

There was no way out. The Black Hills were stolen; the Powder River country and its herds of wild game were gone. Without wild game or rations, the people would starve. The thought of moving far away to a strange country in the south was unbearable, and if the Army took their guns and ponies they would no longer be men.

Red Cloud and his subchiefs signed first, and then Spotted Tail and his people signed. After that the commissioners went to agencies at Standing Rock, Cheyenne River, Crow Creek, Lower Brulé, and Santee, and badgered the other Sioux tribes into signing. Thus did

Paha Sapa,

its spirits and its mysteries, its vast pine forests, and its billion dollars in gold pass forever from the hands of the Indians into the domain of the United States.

Four weeks after Red Cloud and Spotted Tail touched pens to the paper, eight companies of United States cavalry under Three Fingers Mackenzie (the Eagle Chief who destroyed the Kiowas and Comanches in Palo Duro Canyon) marched out of Fort Robinson into the agency camps. Under orders of the War Department, Mackenzie had come to take the reservation Indians’ ponies and guns. All males were placed under arrest, tepees were searched and dismantled, guns collected, and all ponies were rounded up by the soldiers. Mackenzie gave the women permission to use horses to haul their goods into Fort Robinson. The males, including Red Cloud and the other chiefs, were forced to walk to the fort. The tribe would have to live henceforth at Fort Robinson under the guns of the soldiers.

Next morning, to degrade his beaten prisoners even further, Mackenzie presented a company of mercenary Pawnee scouts (the same Pawnees the Sioux had once driven out of their

Powder River country) with the horses the soldiers had taken from the Sioux.

29. Young-Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses. Courtesy of the Nebraska State Historical Society.