Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (54 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

Vickers wrote considerably more, and his article was reprinted across Colorado under the title “The Utes Must Go!” By late summer of 1879, most of the white orators who abounded in frontier Colorado were uttering the applause-producing cry The Utes Must Go! whenever they were called upon to speak in public places.

In various ways the Utes learned that “Nick” Meeker had betrayed them in print. They were especially angry because their agent had said the reservation land did not belong to them, and they delivered a sort of official protest to him through the agency interpreter. Meeker reiterated his statement, and added that he had the right to plow any of the reservation he chose because it was government land and he was the agent of the government.

Meanwhile, William Vickers was accelerating his “Utes Must Go” campaign by manufacturing stories of Indian crimes and outrages. He even blamed the numerous forest fires of that unprecedented drought year on the Utes. On July 5 Vickers prepared a telegram to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for Governor Pitkin’s signature:

Reports reach me daily that a band of White River Utes are off their reservation, destroying forests. … They have already burned millions of dollars of timber and are intimidating settlers and miners. … I am satisfied there is an organized effort on the part of Indians to destroy the timber of Colorado. These savages should be removed to Indian Territory where they can no longer destroy the finest forests in this state.

8

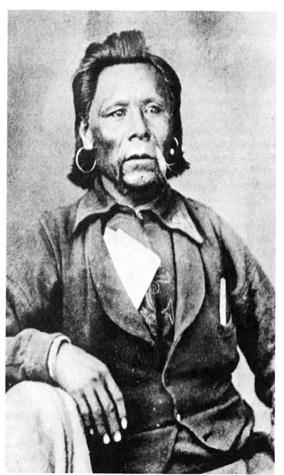

The commissioner replied with a promise to the governor to take action, and then sent a warning to Meeker to keep his Utes on the reservation. When Meeker sent for the chiefs, he discovered they were holding an indignation meeting. They had already heard about the governor’s false charges and his threats to send them to Indian Territory. A white friend named Peck who operated a supply store on Bear River north of the reservation had read the story in a Denver newspaper and told it to Nicaagat (Jack).

According to the news report, the Utes had set fires along Bear River and burned down a house belonging to James B. Thompson, a former Ute agent. Jack was much disturbed by the account, and Peck agreed to go with him to Denver to see Governor Pitkin to tell him that it was not true. They chose a route which would take them by the Thompson house. “We passed by there,” Jack said afterward, “and we saw Thompson’s house standing; it was not burned.”

After a great deal of difficulty, Jack secured admittance to Governor Pitkin’s office. “The governor asked me how things were in my country, on White River, saying that the papers were saying a great deal about us. I told him I thought so myself, and for that reason I had come to Denver. I said I did not understand why this business was in such a state. … He then said, ‘Here is a letter from your Indian agent.’ I told him that, as the Indian agent [Meeker] could write, he had written that letter; but that I, not being able to write, had come to see him in person and answer it. That much we talked; and then I told him I did not wish him to believe what was written in that letter. … He asked me if it was true that Thompson’s house was burned. I told him that I had seen the house—that it was not burned. I then talked to the governor about the Indian agent, and told him it would be well for him to write to Washington and recommend that some other agent be put in his place, and he promised to write the next day.”

9

Pitkin, of course, had no intention of recommending a replacement for Meeker. From the governor’s viewpoint, everything was moving in the right direction. All he had to do was wait for a showdown between Meeker and the Utes, and then perhaps—“The Utes Must Go!”

About this same time, Meeker was preparing his monthly report for the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He wrote that he was planning to establish a police force among the Utes. “They are in a bad humor,” he added, yet only a few days later he initiated actions which he surely must have known would make the Utes even more belligerent. Although there is no direct evidence that Meeker sympathized with Governor Pitkin’s “Utes Must Go” program, almost every step he took seemed designed to arouse the Indians to revolt.

Meeker may not have wanted the Utes to go, but he certainly wanted their ponies banished. Early in September he ordered one of his white workmen, Shadrach Price, to begin plowing a section of grassland on which the Utes pastured their ponies. Some of the Utes protested immediately, asking Meeker why he did not plow somewhere else; they needed the grass for their ponies. West of the pasture was a section of sageland, which Quinkent (Douglas) offered to clear for plowing, but Meeker

stubbornly insisted upon plowing up the grass. The Utes’ next move was to send out a few young men with rifles. They approached the plowman and ordered him to stop. Shadrach Price obeyed, but when he reported the threat to Meeker, the agent sent him back to finish his work. This time the Utes fired warning shots above Price’s head, and the plowman hurriedly unhitched his horses and left the pasture.

Meeker was furious. He composed an indignant letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. “This is a bad lot of Indians,” he wrote; “they have had free rations so long, and have been flattered and petted so much, that they think themselves lords of all.”

10

That afternoon the medicine man, Canalla (Johnson), came to the agency office to see Meeker. He told Meeker that the land being plowed had been assigned to him for pasturing his ponies. Now that the plowing was stopped, he did not want it started again.

Meeker interrupted Johnson’s impassioned speech. “The trouble is this, Johnson. You have too many ponies. You had better kill some of them.”

11

For a moment Johnson stared at Meeker in disbelief. Suddenly he moved toward the agent, caught him by the shoulders, pushed him out on the porch, and shoved him against the hitching rail. Without saying a word, Johnson then stalked away.

Johnson afterward related his version of the incident: “I told the agent that it was not right that he should order the men to plow my land. The agent told me I was always a troublesome man, and that it was likely I might come to the calaboose. I told him that I did not know why I should go to prison. I told the agent that it would be better for another agent to come, who was a good man, and was not talking such things. I then took the agent by the shoulder and told him it was better that he should go. Without doing anything else to him—striking him or anything else—I just took him by the shoulder. I was not mad at him. Then I went to my house.”

12

Before Meeker took further action, he summoned Nicaagat (Jack) to his office for a talk. Jack later recalled the meeting: “Meeker told me that Johnson had been mistreating him. I told Meeker that it was nothing, that it was a small matter and he

had better let it drop. Meeker said it didn’t make any difference; that he would mind it and complain about it. I still told him that it would be a very bad business to make so much fuss about nothing. Meeker said he didn’t like to have a young man take hold of him, that he was an old man and had no strength to retaliate, and he didn’t want to have a young man take hold of him in that way; he said that he was an old man and Johnson had mistreated him and he would not say any more to him; that he was going to ask the commissioner for soldiers and that he would drive the Utes from their lands. Then I told him it would be very bad to do that. Meeker said that anyhow the land did not belong to the Utes. I answered that the land did belong to the Utes, and that was the reason why the government had the agencies there, because it was the Utes’ land, and I told him again that the trouble between him and Johnson was a very small matter and he had better let it drop and not make so much fuss about it.”

13

For another day and night Meeker brooded over his deteriorating relations with the Utes, and then he finally made up his mind that he must teach them a lesson. He dispatched two telegrams, one to Governor Pitkin asking for military protection, another to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs:

I have been assaulted by a leading chief, Johnson, forced out of my own house, and injured badly. It is now revealed that Johnson originated all the trouble. … His son shot at the plowman, and the opposition to plowing is wide. Plowing stops; life of self, family, and employees not safe; want protection immediately; have asked Governor Pitkin to confer with General Pope.

During the following week, the ponderous machineries of the Interior and War departments slowly moved into action. On September 15 Meeker received notice that orders were being transmitted to cavalry units to march to White River; the agent was authorized to arrest “leaders in the late disturbance.”

14

The War Department dispatched orders to Major Thomas T. Thornburgh, commanding at Fort Fred Steele, “to move with a sufficient number of troops to the White River Ute agency, Colorado, under special instructions.” Because Thornburgh was

on an elk hunt, the orders were delayed in reaching him, and he did not move out until September 21. For the 150-mile march to White River, he outfitted about two hundred cavalrymen and mounted infantrymen.

15

On September 25 Thornburgh reached Fortification Creek. The column was about halfway to the White River agency, and the major decided to send one of his guides ahead to notify Meeker that he could reach the agency in four more days; he asked Meeker to inform him of the current situation there. On that same day, Colorow and Nicaagat (Jack) learned of the approaching soldiers; the Ute chiefs were moving with their people toward Milk River for the customary autumn hunts.

Jack rode north to Bear River and met the troops there. “What is the matter?” he asked them. “What are you coming for? We do not want to fight with the soldiers. We have the same father over us. We do not want to fight them.”

Thornburgh and his officers told Jack that they had received a telegram to go to the agency; that the Indians were burning up the forests around there and had burned Mr. Thompson’s cabin. Jack replied that it was a lie; the Utes had not burned any forests or cabins. “You leave your soldiers here,” he said to Thornburgh. “I am a good man. I am Nicaagat. Leave your soldiers here, and we will go down to the agency.” Thornburgh replied that he had orders to march his soldiers to the agency. Unless he received word from agent Meeker to halt the column, he would have to take the soldiers on to White River.

16

Jack again insisted that the Utes did not want to fight. He said it was not good that soldiers were coming into their reservation. Then he left Thornburgh and hurried back to the agency to warn “Nick” Meeker that bad things would happen if he let the soldiers come to White River.

On the way to Meeker’s office, Jack stopped to see Quinkent (Douglas). They were rival chiefs, but now that all the White River Utes were in danger, Jack felt that the leaders must not be divided. The young Utes had heard too much talk about the white men sending them off to Indian Territory; some said they had heard Meeker boast that the soldiers were bringing a wagonload of handcuffs and shackles and ropes and that several bad Utes would be hanged and others taken as prisoners. If they

believed the soldiers were coming to take them away from their homeland, they would fight them to the death, and not even the chiefs could stop them from fighting. Douglas said that he wanted nothing to do with it. After Jack left, he put his American flag on a pole and mounted it above his lodge. (Perhaps he had not heard that Black Kettle of the Cheyennes was flying an American flag at Sand Creek in 1864.)

“I told the agent [Meeker] that the soldiers were coming,” Jack said, “and that I hoped he would do something to stop their coming to the agency. He said it was none of his business; he would have nothing to do with it. I then said to the agent I would like he and I to go where the soldiers were, to meet them. The agent said that I was all the time molesting him; he would not go. This he told me in his office; and after finally speaking he got up and went into another room, and shut and locked the door. That was the last time I ever saw him.”

17

Later in the day, Meeker evidently changed his mind and decided to heed Jack’s advice. He sent a message to Major Thornburgh, suggesting that he halt his column and then come to the agency with an escort of five soldiers. “The Indians seem to consider the advance of the troops as a declaration of real war,” he wrote.

18

On the following day (September 28), when the message reached Thornburgh’s camp on Deer Creek, Colorow also arrived there to try to convince the major that he should proceed no farther. “I told him I did not know at all why the troops had come,” Colorow said afterward, “or why there should be war.”

19

The column was then only thirty-five miles from White River agency.

After reading Meeker’s message, Thornburgh told Colorow that he would move his troops down to the Milk River boundary of the Ute reservation; there he would camp his soldiers, and then he and five men would go on to the agency to confer with Meeker.

Not long after Colorow and his braves left Thornburgh’s camp, the major held an officers’ meeting, during which he decided to change his plans. Instead of halting on the edge of the reservation, the column would march on through Coal Creek Canyon. This was a military necessity, Thornburgh explained,

because Colorow’s and Jack’s camps were just below it. If the troops halted on Milk River, and the Utes decided to block the canyon, they could keep the soldiers from reaching the agency. From the south end of the canyon, however, only a few miles of open country would lie between them and White River.