Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (6 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

When General Carleton heard that there was a chance of Manuelito surrendering, he sent four carefully chosen Navahos from the Bosque (but not Herrero Grande) to use their influence on the reluctant war chief. They did not convince Manuelito. One June night after they had talked, Manuelito and his band vanished from Quelitas and went back to their hiding places along the Little Colorado.

In September he heard that his old ally Barboncito had been

captured in the Canyon de Chelly. Now he, Manuelito, was the last of the

rico

holdouts, and he knew the soldiers would be looking everywhere for him.

During the autumn, Navahos who had escaped from the Bosque Redondo began returning to their homeland with frightening accounts of what was happening to the people there. It was a wretched land, they said. The soldiers prodded them with bayonets and herded them into adobe-walled compounds where the soldier chiefs were always counting them and putting numbers down in little books. The soldier chiefs promised them clothing and blankets and better food, but their promises were never kept. All the cottonwood and mesquite had been cut down, so that only roots were left for firewood. To shelter themselves from rain and sun they had to dig holes in the sandy ground, and cover and line them with mats of woven grass. They lived like prairie dogs in burrows. With a few tools the soldiers gave them they broke the soil of the Pecos bottomlands and planted grain, but floods and droughts and insects killed the crops, and now everyone was on half-rations. Crowded together as they were, disease had begun to take a toll of the weaker ones. It was a bad place, and although escape was difficult and dangerous under the watchful eyes of the soldiers, many were risking their lives to get away.

Meanwhile, Star Chief Carleton had persuaded the Vicario of Santa Fe to sing a Te Deum in celebration of the Army’s successful removal of the Navahos to the Bosque, and the general described the place to his superiors in Washington as “a fine reservation … there is no reason why they [the Navahos] will not be the most happy and prosperous and well-provided-for Indians in the United States. … At all events … we can feed them cheaper than we can fight them.”

In the eyes of the Star Chief, his prisoners were only mouths and bodies. “These six thousand mouths must eat, and these six thousand bodies must be clothed. When it is considered what a magnificent pastoral and mineral country they have surrendered to us—a country whose value can hardly be estimated—the mere pittance, in comparison, which must at once be given to support them, sinks into insignificance as a price for their natural heritage.”

And no advocate of Manifest Destiny ever phrased his support of that philosophy more unctuously than he: “The exodus of this whole people from the land of their fathers is not only an interesting but a touching sight. They have fought us gallantly for years on years; they have defended their mountains and their stupendous canyons with a heroism which any people might be proud to emulate; but when, at length, they found it was their destiny, too, as it had been that of their brethren, tribe after tribe, away back toward the rising of the sun, to give way to the insatiable progress of our race, they threw down their arms, and, as brave men entitled to our admiration and respect, have come to us with confidence in our magnanimity, and feeling that we are too powerful and too just a people to repay that confidence with meanness or neglect—feeling that having sacrificed to us their beautiful country, their homes, the associations of their lives, the scenes rendered classic in their traditions, we will not dole out to them a miser’s pittance in return for what they know to be and what we know to be a princely realm.”

11

Manuelito had not thrown down his arms, however, and he was too important a chief for General Carleton to permit such incorrigibility to continue unchallenged. In February, 1865, Navaho runners from Fort Wingate brought Manuelito a message from the Star Chief, a warning that he and his band would be hunted down to the death unless they came in peaceably before spring. “I am doing no harm to anyone,” Manuelito told the messengers. “I will not leave my country. I intend to die here.” But he finally agreed to talk again with some of the chiefs who were at the Bosque Redondo.

In late February, Herrero Grande and five other Navaho leaders from the Bosque arranged to meet Manuelito near the Zuni trading post. The weather was cold, and the land was covered with deep snow. After embracing his old friends, Manuelito led them back into the hills where his people were hidden. Only about a hundred men, women, and children were left of Manuelito’s band; they had a few horses and a few sheep. “Here is all I have in the world,” Manuelito said. “See what a trifling amount. You see how poor they are. My children are eating palmilla roots.” After a pause he added that his horses were in no condition for travel to the Bosque. Herrero replied that he

had no authority to extend the time set for him to surrender, and he warned Manuelito in a friendly way that he would be risking the lives of his people if he did not come in and surrender. Manuelito wavered. He said he would surrender for the sake of the women and children; then he added that he would need three months to get his livestock in order. Finally he declared flatly that he could not leave his country.

“My God and my mother live in the West, and I will not leave them. It is a tradition of my people that we must never cross the three rivers—the Grande, the San Juan, the Colorado. Nor could I leave the Chuska Mountains. I was born there. I shall remain. I have nothing to lose but my life, and

that

they can come and take whenever they please, but I will not move. I have never done any wrong to the Americans or the Mexicans. I have never robbed. If I am killed, innocent blood will be shed.”

Herrero said to him: “I have done all I could for your benefit; have given you the best advice; I now leave you as if your grave were already made.”

12

In Santa Fe a few days later Herrero Grande informed General Carleton of Manuelito’s defiant stand. Carleton’s response was a harsh order to the commander at Fort Wingate: “I understand if Manuelito … could be captured his band would doubtless come in; and that if you could make certain arrangements with the Indians at the Zuni village, where he frequently comes on a visit and to trade, they would cooperate with you in his capture. … Try hard to get Manuelito. Have him securely ironed and carefully guarded. It will be a mercy to others whom he controls to capture or kill him at once. I prefer he should be captured. If he attempts to escape … he will be shot down.”

13

But Manuelito was too clever to fall into Carleton’s trap at Zuni, and he managed to avoid capture through the spring and summer of 1865. Late in the summer Barboncito and several of his warriors escaped from Bosque Redondo; they were said to be in the Apache country of Sierra del Escadello. So many Navahos were slipping away from the reservation that Carleton posted permanent guards for forty miles around Fort Sumner. In August the general ordered the post commander to kill every Navaho found off the reservation without a pass.

When the Bosque’s grain crops failed again in the autumn of 1865, the Army issued the Navahos meal, flour, and bacon which had been condemned as unfit for soldiers to eat. Deaths began to rise again, and so did the number of attempted escapes.

Although General Carleton was being openly criticized now by New Mexicans for conditions at Bosque Redondo, he continued to hunt down Navahos. At last, on September 1, 1866, the chief he wanted most—Manuelito—limped into Fort Wingate with twenty-three beaten warriors and surrendered. They were all in rags, their bodies emaciated. They still wore leather bands on their wrists for protection from the slaps of bowstrings, but they had no war bows, no arrows. One of Manuelito’s arms hung useless at his side from a wound. A short time later Barboncito came in with twenty-one followers and surrendered for the second time. Now there were no more war chiefs.

Ironically, only eighteen days after Manuelito surrendered, General Carleton was removed from command of the Army’s Department of New Mexico. The Civil War, which had brought Star Chief Carleton to power, had been over for more than a year, and the New Mexicans had had enough of him and his pompous ways.

When Manuelito arrived at the Bosque a new superintendent was there, A. B. Norton. The superintendent examined the soil on the reservation and pronounced it unfit for cultivation of grain because of the presence of alkali. “The water is black and brackish, scarcely bearable to the taste, and said by the Indians to be unhealthy, because one-fourth of their population have been swept off by disease.” The reservation, Norton added, had cost the government millions of dollars. “The sooner it is abandoned and the Indians removed, the better. I have heard it suggested that there was speculation at the bottom of it. … Do you expect an Indian to be satisfied and contented deprived of the common comforts of life, without which a white man would not be contented anywhere? Would any sensible man select a spot for a reservation for 8,000 Indians where the water is scarcely bearable, where the soil is poor and cold, and where the muskite [mesquite] roots 12 miles distant are the only wood for the Indians to use? … If they remain on this reservation

they must always be held there by force, and not from choice. O! let them go back, or take them to where they can have good cool water to drink, wood plenty to keep them from freezing to death, and where the soil will produce something for them to eat. …”

14

For two years a steady stream of investigators and officials from Washington paraded through the reservation. Some were genuinely compassionate; some were mainly concerned with reducing expenditures.

“We were there for a few years,” Manuelito remembered. “Many of our people died from the climate. … People from Washington held a council with us. He explained how the whites punished those who disobeyed the law. We promised to obey the laws if we were permitted to get back to our own country. We promised to keep the treaty. … We promised four times to do so. We all said ‘yes’ to the treaty, and he gave us good advice. He was General Sherman.”

When the Navaho leaders first saw the Great Warrior Sherman they were fearful of him because his face was the same as Star Chief Carleton’s—fierce and hairy with a cruel mouth—but his eyes were different, the eyes of a man who had suffered and knew the pain of it in others.

“We told him we would try to remember what he said,” Manuelito recalled. “He said: ‘I want all you people to look at me.’ He stood up for us to see him. He said if we would do right we could look people in the face. Then he said: ‘My children, I will send you back to your homes.’”

Before they could leave, the chiefs had to sign the new treaty (June 1, 1868), which began: “From this day forward all war between the parties to this agreement shall forever cease.” Barboncito signed first, then Armijo, Delgadito, Manuelito, Herrero Grande, and seven others.

“The nights and days were long before it came time for us to go to our homes,” Manuelito said. “The day before we were to start we went a little way towards home, because we were so anxious to start. We came back and the Americans gave us a little stock and we thanked them for that. We told the drivers to whip the mules, we were in such a hurry. When we saw the top of the mountain from Albuquerque we wondered if it was

our mountain, and we felt like talking to the ground, we loved it so, and some of the old men and women cried with joy when they reached their homes.”

15

3. A Navaho warrior of the 1860’s. Photographed by John Gaw Meem and reproduced by permission of the Denver Art Museum.

And so the Navahos came home. When the new reservation lines were surveyed, much of their best pastureland was taken away for the white settlers. Life would not be easy. They would have to struggle to endure. Bad as it was, the Navahos would come to know that they were the least unfortunate of all the western Indians. For the others, the ordeal had hardly begun.

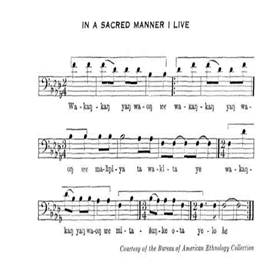

In a sacred manner