Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (3 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

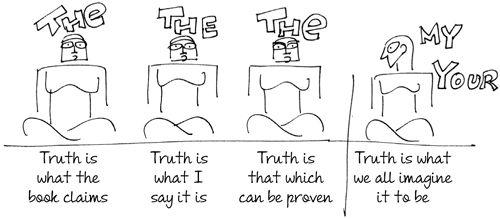

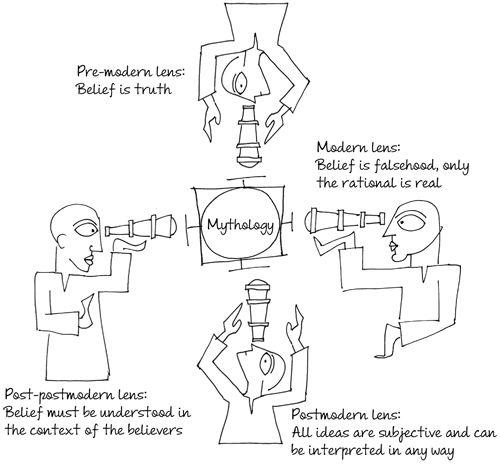

Myth has since been positioned as being the opposite of the truth. Unfortunately, in the West, truth is claimed on one hand by scientists and on the other hand by religious authorities. There is much debate even today between the theists and atheists. Academicians and scientists have legitimized this fight by joining in. This fight has been appropriated by most societies in the world that seek to be modern.

But the divide between myth and truth, between religious truth and scientific truth, this rabid quest for the absolute and perfect truth is a purely Western phenomenon. It would not have bothered the intellectuals of ancient China who saw such activities as speculative indulgence. Ancient Indian sages would have been wary of it for they looked upon the quest for the objective and absolute as the root cause of intolerance and violence.

The ‘modern era’ that flourished after the scientific revolution of Europe mocked the ‘pre-modern era’ that did not challenge irrational ideas propagated by religious and royal authorities.

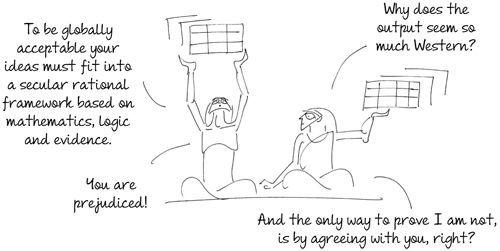

In the second half of the twentieth century, people started observing that rational ideas propagated by modern scientists, especially social scientists, in the realm of economics, politics, sociology, anthropology, philosophy, arts, religious and cultural studies, were also steeped in prejudice. The language used to express ideas harboured cultural ideas: innocuous words like ‘evolution’ and ‘development’ revealed a belief that the world had, or should have, a purpose, a direction, and a movement towards betterment. Capitalism and Communism were deconstructed to reveal roots in the Greek epics or the Bible as they spoke of individualistic heroes and martyrdom for the greater social good. This discovery gave birth to the ‘postmodern era’. Modern ideas may not be religious, but that did not make them universal truths; they were as rooted in cultural beliefs as the superstitions of yore.

But there was a problem with the postmodern revolution. It implicitly suggested that everything was up for interpretation, there was no correct decoding, and no view could be criticized, as everything was subjective. Judgment of any kind was bad; any form of evaluation was prejudice. The era of remixes was born. Ravan could be worshipped and Ram reviled, invalidating the traditional adoration of Ram in hundreds of temples over hundreds of years. Images of Santa on a crucifix could be used to evoke the Christmas spirit.

Another problem with the postmodern lens is that the authors are typically critical of the authoritarian and manipulative gaze but are indifferent to their own gaze, which is often equally authoritarian and manipulative. Deconstruction of the Other is rarely accompanied by deconstruction of the self.

Today people speak of ‘post-postmodernism’. It means looking at beliefs from the point of view of the believer. It demands empathy and less judgment, something that is in short supply in academia today, as it is designed to argue and dismiss ideas in its quest for the objective truth.

Connecting Mythology and Management

I discovered my love for mythology while studying in Grand Medical College, Mumbai. After my graduation, I chose to work in the medical industry, rather than take up clinical practice, to give myself the time and funds for my passion. So I lived in two worlds: weekdays in the pharmaceutical and healthcare industry and weekends with mythologies from all over the world.

In my professional capacity, I was first a content vendor, then a manager at

Goodhealthnyou.com

, Apollo Health Street and Sanofi Aventis, and finally, a business adviser at Ernst Young. In a personal capacity, I conducted workshops as part of Sabrang, an organization dedicated to demystifying the arts, started by the late Parag Trivedi. Conversations with him, and other members of the Sabrang gang, revealed a gap between Hindustani melody and Western harmony, the value of facial expressions in Indian classical dance and the relative absence of the same in Japanese theatre, ballet and modern American dance, the intense arguments of European philosophers on the nature of the truth and the reason why Indian, or Chinese, philosophers were excluded from these arguments. Shifts in patterns I had seen in stories, symbols and rituals, were now apparent in music, dance, architecture, and philosophy.

I never studied management formally though I grew up listening to stories of sales and marketing from my father who did his MBA from New York University in 1960, long before it became fashionable in India (IIM itself was founded in 1961). One of his teachers was the famous Peter Drucker. My father returned to work in the private sector in India at the height of the licence raj. He always spoke of trust, relationships and respect, rather than processes and control.

I did do a formal postgraduate diploma course in comparative mythology from Mumbai University, but it was too rudimentary for my liking. I delved into the literature written around the subject (

Myth

by Lawrence Coupe, for example) and realized that mythology demanded forging links with literature, language, semiotics, the occult, mysticism, anthropology, sociology, philosophy, religion, history, geography, business, economics, politics, psychology, physics, biology, natural history, archaeology, botany, zoology, critical thinking, and the arts. Courses offered by universities abroad, on the other hand, were not inter-disciplinary enough. Self-study was the only recourse.

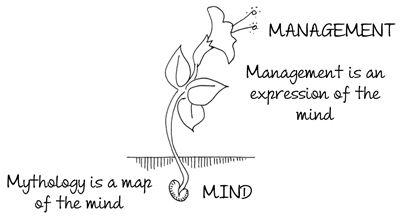

The more I explored mythology, the more I felt like Aladdin in a cave of undiscovered treasures. Every day I learned something that took me by surprise. I realized how mythology tends to be read literally, causing it to be seen through a sociological and historical lens (did Ram exist?) when, in fact, its greatest value comes when it is read symbolically and seen in psychological terms (what aspect of our personality does Ram represent?).

As my mind exploded with new ideas, I wondered if they were true. And this lead to the unearthing of various theories on truth that helped me understand myth even better. It exposed the gap between neuroscience and psychoanalysis and the discomfort of scientists with the idea of imagination. It also revealed how the truth of the East is always studied in Western terms, rarely has the truth of the West been studied in Eastern terms. If it has, it has been dismissed as exotic, even quaint.

For a long time, management and mythology were parallel rivers in my life, unconnected with each other. Things began to change when I became increasingly sensitive to the problems plaguing corporations: the power play between sales and marketing, the need as well as threat of unions, the burden of templates, the cultural insensitivity of multinational advertising, the lack of inter-departmental empathy, the pretence of teamwork, the tyranny of technology, the feudal mindset beneath institutional veneers, the horrors of mergers and acquisitions, the deceptiveness of valuations, and the harsh reality of balance sheets.

I was fortunate that early in my career I interacted with Dr. Giri Shankar and his wife, Shailaja, who came from a strong behavioural science background, which is the cornerstone of many human resource practices in the business world. The frameworks they provided explained and helped resolve many of the issues I saw and faced. But our intense and illuminating conversations kept telling me that something was missing. I found the subject too rational, too linear and too neat. Then it dawned on me that both management science and behavioural science have originated in American and European universities and are based on a Western template. Practitioners of behavioural science use questionnaires to map the mind in objective mathematical terms but the subject itself springs from Jungian psychoanalysis and the notion of archetypes, which is eager to be ‘universal’ despite being highly subjective, and skewed towards mythologies of Western origin.

The problems of the corporate world made more sense when I abandoned the objective, and saw things using a subjective or mythic lens. It revealed the gap in worldviews as the root of conflict, frustration and demotivation. Modern management systems were more focused on an objective institutional truth, or the owner’s truth, rather than individual truths. People were seen as resources, to be managed through compensation and motivation. They were like switches in a circuit board. But humans cannot be treated as mere instruments. They have a neo-frontal cortex. They imagine. They have beliefs that demand acknowledgment. They imagine themselves as heroes, villains and martyrs. They yearn for power and identity. Their needs will not go away simply by being dismissed as irrational, unscientific or unnecessary. Knowledge of mythology, I realized, could help managers and leaders appreciate better the behaviour of their investors and regulators, employers and employees and competitors and customers. Mythology is, after all, the map of the human mind.

The management framework is rooted in Greek and biblical mythologies. The Indian economic, political and education systems are also rooted in Western beliefs, but Indians themselves are not. What would be a very Indian approach to management, I wondered. Since the most popular mode of expression, in India, was the mythic, I chose to glean business wisdom from the grand jigsaw puzzle of stories, symbols and rituals that originated and thrived in the Indian subcontinent, especially in the Hindu, Jain, Buddhist and Sikh faiths.

The patterns I found revealed something very subtle and startling very early on. Belief itself, as conventionally approached in modern times, is very different from the traditional Indian approach:

- The desire to evangelize and sell one idea and dismiss others reveals the belief that one belief is better, or right. Missionaries evangelize, social activists evangelize, and politicians evangelize; management gurus also evangelize. Everyone wants to debate and win. There is celebration of competition and revolution. In other words; only one belief is allowed to exist, weeding out other beliefs. This explains the yearning for a globally applicable morality and ethics, ignoring local contexts. At best, allowances are made for the professional and personal space. This value placed on a single belief, religious or secular, naturally makes a society highly efficient. Since changing beliefs is difficult, perhaps even impossible, the attention shifts to behavioural modification through rationality, righteousness, rules, reward and reproach. In fact, great value is given to ‘habits’, which is essentially conditioning and a lack of mindfulness. Thus value is given to changing the world, as people cannot be changed. This is typical of beliefs rooted in one life, religions that value only one God.

- The notion of conversion is alien to Indian faiths. Greater value is given to changing oneself, than the world. Belief in India is not something you have; it is what makes you who you are. It shapes your personality. Different people have different personalities because they believe in different things. Every belief, every personality, is valid. Energy has to be invested in accommodating people rather than judging their beliefs. That is why there is so much diversity. We may not want to change our beliefs, but we can always expand our mind to accommodate other people’s beliefs. Doing so, not only benefits the other, it benefits us too, for it makes us wiser, reveals the patterns of the universe. But we struggle to expand our mind as growth is change, and change is frightening. Our belief, our personality, marks the farthest frontier of our comfort zone, beyond which we are afraid to go. Such ideas thrive in beliefs rooted in many lives, and religions that value many gods.