Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (44 page)

Unseen, we are compelled to fend for ourselves

A fisherman catches a river fish, inside which he finds, miraculously, a pair of twins: a boy and a girl. The fisherman takes the children to Ushinara, the childless king of the land. The king adopts the boy, not the girl. She is named Satyavati and raised among the fishermen.

When Satyavati grows up she ferries people across the river. Shantanu, the old king of Hastinapur, falls in love with her and wants to marry her, but the leader of the fishermen says, "Only if her sons inherit your throne."

Shantanu has a son called Devavrat from an earlier marriage. To make his father happy, Devavrat gives up his claim to the throne, paving the way for Satyavati to marry his father. "But what if your children fight my children?" says Satyavati.

The roots of Satyavati's ambitions lay in her rejection by Ushinara who preferred the male child to the female child. She, who was not allowed to be princess, now wants to be queen and mother of kings. She wants to be seen as she imagines herself.

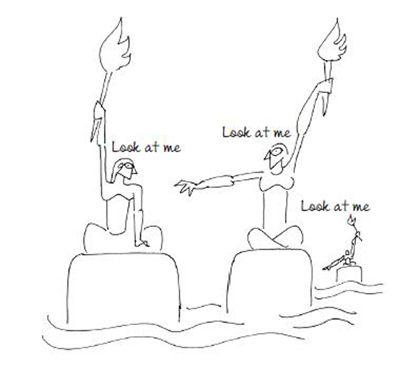

Our desire to achieve does not happen in isolation. We seek an audience. When the audience refuses to cheer for us, we work hard until they admire us. We validate ourselves, like Satyavati, through the Other. The Other is the parent whose attention we crave.

Nandita's dream has come true. She is a successful television actress. She has the best role she could have ever imagined and she is paid very well. The days of struggle are over. The audiences love her, as indicated by the ratings of her show. Still, every day she throws tantrums on the sets. She arrives late, refuses to come out of her trailer until the director begs her to, demands audiences with the television channel head, and insists on changing dialogues at the last minute. Unless she does this, she feels she is not being given her due. She is worth so much more. She was happiest when a trade journal revealed that she was the highest paid television star in history. She felt she had finally been seen.

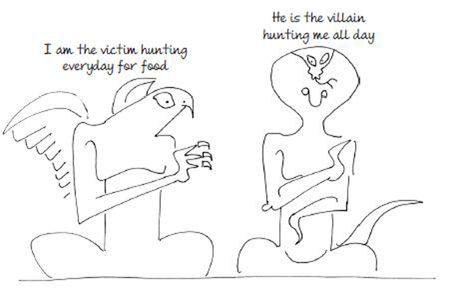

We refuse to see ourselves as villains

Naraka, the asura, attacks Amravati and drives Indra out, laying claim to the treasures of paradise. Indra seeks the help of Vishnu and gets anxious when there is no sign of him in Vaikuntha. He is directed to Krishna, who lives on earth, and is considered to be Vishnu incarnate.

Indra doubts Krishna's divinity but desperate, seeks his help anyway. To his surprise, Krishna summons and mounts the eagle Garud and, with his wife Satyabhama by his side, rises to the sky bearing his resplendent weapons to battle with Naraka. After an intense battle, Krishna manages to vanquish Naraka and Indra regains his kingdom.

Naraka is no ordinary asura. He is the son of the earth-goddess, Bhudevi, and Varaha, the boar avatar of Vishnu who had rescued Bhudevi from the bottom of the sea after she had been dragged there by the asura, Hiranayaksha. When Krishna kills Naraka, Vishnu effectively kills his own son, but Indra is not even aware of this.

While leaving, Satyabhama expresses her desire for the parijata tree that grows in Indra's courtyard. Indra, however, refuses to part with it. Indra's refusal shocks Satyabhama who now becomes adamant about taking the tree back with her to earth. So Krishna takes it by force. When Indra tries to stop Krishna, another battle follows, this time with the devas, in which Indra is predictably defeated.

The story reveals the character of Indra. He is desperate to get help from Krishna but is unwilling to share even a tree with his saviour. He wants things, but never gives things. The king of the devas is not known for his generosity. He clings to his paradise but cannot enjoy it as he continuously fears losing it. His clinginess creates circumstances that contribute to his losing control over Amravati. When he manages to get it back with a little help from Vishnu, he returns to his clingy ways. Misfortune makes him miserable but fortune does not make him gracious. Circumstances teach him nothing as he is convinced he has nothing to learn. When this is pointed out, people like Indra simply shrug their shoulders, become defensive and say: we are like this only.

And so at the workplace, Indra comes to your workstation only because he wants something. He expects you to do it because that is your job. But when you ask him for something, he refuses to help as he feels you are asking for a favour.

When Murli calls John, John knows that there is trouble in the family. Murli is one of the star directors of a family business and John is the head of accounts. Whenever the family members have a fight Murli calls John and spends hours saying nasty things about the family, claiming they are ganging up against him. John knows never to take these things seriously. Once the family dispute is settled, Murli will stop calling John and start maligning John lest John reveal what was said in those earlier phone calls. Everybody thinks that John is close to the family but John knows that no matter how loyal he is, how well he performs, he will never ever be a member of the family, never a shareholder of the company, regardless of the many promises made by Murli. John's wife says he should ask for his rights. "Rights?" John replies with amusement, "I only have a salary that I get paid every month. Everything else is just wishful thinking." John knows that Indra will not part with his parijata tree. John also knows he is no Krishna capable of overpowering his Indra.

We use work as a beacon to get attention

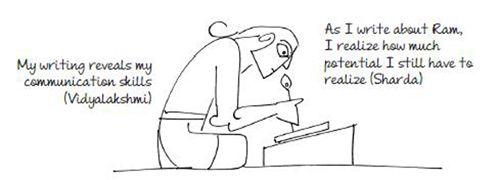

After Valmiki writes the Ramayan, he learns that Hanuman has also written a Ramayan. Curious about Hanuman's version, he goes to the distant plantain forest in the warm valleys cradled by the Himalayas where Hanuman lives.

There he finds the banana leaf on which Hanuman has etched his version of Ram's tale. The vocabulary, grammar, melody and metre are so perfect that Valmiki starts to cry, "After reading Hanuman's Ramayan, nobody will read Valmiki Ramayan." On hearing this, Hanuman tears the banana leaf with the epic on it, crushes it into a ball, pops it into his mouth and swallows it. "Why did you do that?" asks a surprised Valmiki.

Hanuman replies, "You need your Ramayan more than I need my Ramayan. You wrote your Ramayan because you want the world to remember you. I wrote my Ramayan because I wanted to remember Ram."

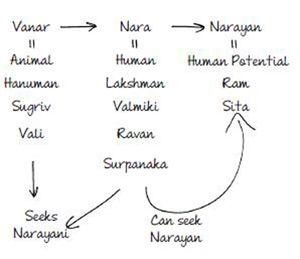

Ram embodies Narayan, human potential. Valmiki is nara, the human being. Hanuman is vanar, a monkey and an animal—less than human because he is not blessed with the power of imagination. Still, it is Hanuman who sees his work as an exercise to discover what he is capable of becoming while Valmiki sees his work as a beacon to gather fame, attention and validation. Hanuman seeks Narayan while Valmiki seeks Narayani. Narayan helps us see others. Narayani gets others to see us.

It is important to remind ourselves of who it is we work for. While the official purpose of work is to satisfy customers, employers, employees, shareholders and family, the unofficial purpose of work is to satisfy ourselves, feel noticed and alive.

Our work can become the tool that helps us grow not just materially but also emotionally and intellectually. It can widen our gaze. Valmiki, without realizing it, focuses only on material growth; Hanuman focuses on emotional and intellectual growth. When we widen our gaze, material growth follows. But the reverse is not true.

Lakotiaji has established some of the finest educational institutions in areas that did not have, until twenty years ago, even a decent primary school. Because of him many children have been educated and many adults have got jobs. The business has made him very rich, a much-respected member of the community. But Lakotiaji is upset. "The government has not recognized me. I deserve a Padma Shri." He is currently lobbying local politicians and the media hoping someone will recommend his name.

Our goals justify our lack of a caring gaze

In the Mahabharat, every character is invisible. Nobody sees anybody. Everyone is too busy gazing at ideals and institutions until Krishna arrives.

Bhisma sacrifices property and conjugal rights so that his old father, Shantanu, can marry Satyavati. Before long, the celibate and childless Bhisma finds himself responsible for Satyavati's children, grandchildren and her great-grandchildren. Since he sacrificed everything to please his father, he expects the children of the household to display similar selflessness and nobility. Fears and insecurities of individual family members are dismissed as being self-indulgent. So fixed is his gaze on family name that the family members feel small and invalidated.

Before long, the gaze of his great grandchildren shrinks. The Pandavs and Kauravs start seeing the kingdom as their property more than responsibility. They start valuing the kingdom more than each other. This marks the downfall of the household. But at no point does anyone see the venerable ancestor's sacrifice as contributing to the downward spiral. Even Bhisma blames external influences for family problems, never once gazing upon his own gaze.

Often leaders are so consumed by their personal values and agendas that they expect their followers to be as excited about what matters to them. They get angry with followers who resist or refuse to keep pace. Those who align with their goals are celebrated. The rest are condemned as selfish.

For many, the whole purpose of existence is self-actualization and thus, they voluntarily isolate themselves from the rest of the ecosystem. Nothing matters except their goals and ambitions. Achieving them makes them heroes while the failure to do so makes them martyrs. No one looks at the string of disappointed faces and broken hearts that they leave behind in their wake. Feelings don't matter when we do business, we are told. We are taught to believe that if it is not personal, it is okay to hurt.

At the open house session, the staff of an organization that sold mobile toilets complained that they were being forced to work overtime. They were promised a half-day on Saturday, but they ended up working late. The owner, Purab, shouted, "I work much more than you do, twice as much, so I expect you to give more. Isn't this work noble? We are liberating people from the humiliation of open toilets. How can you ask for holidays when there are people who do not have even basic amenities?" The staff immediately kept quiet. No one pointed out that they were not shareholders, they were not going to get a share of the profit and that their salaries would not rise proportionately if the business grew. They did not care for Purab's ideals or vision. They felt embarrassed telling their families about their jobs. The staff felt that Purab would see such candid views as subversive and threatening so they kept quiet, submitting to what each one imagined to be exploitation. Purab kept grumbling about the absence of ownership amongst the staff for the noble vision of his organization. Purab is Bhisma, so blinded by his vision that he does not see his staff is made of Indras seeking higher returns with low investment. He refuses to see how, for centuries, Indians have always looked down upon those who clean toilets.