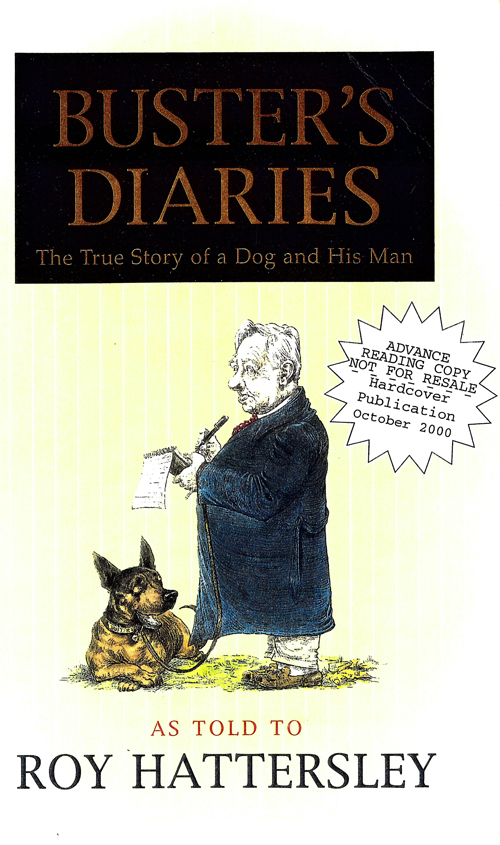

Buster's Diaries: The True Story of a Dog and His Man

Read Buster's Diaries: The True Story of a Dog and His Man Online

Authors: Roy Hattersley

Text Copyright © 1998 by Roy Hattersley

Illustrations Copyright © 1998 by Chris Riddell

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: November 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-57019-0

Contents

My brother and I were born in the overgrown back garden of a house in Paddington London, sometime during February 1995. When

we were a few days old, our mother was bitten by a rat and the man who owned her tied her to a fence post and left her to

die. For nearly a week, she survived on water which was leaking from a hose, and she fed us till she died. Then Diana, the

lady who lived next door, rescued us. Being too young and stupid to recognize kindness, after a couple of weeks we ran away

and started to live rough. It was the beginning of my fascination with garbage. Even now, with two square meals a day and

more biscuits than are good for me, I find black bags and garbage cans irresistible.

We had been vagrants for more than two months when Doris Turner saw us running about on Paddington Recreation Ground. Doris

ran the Brent Animal Shelter and decided at once that she must find us a good home. Even then, for reasons I can’t explain,

I longed for human company. So when Doris called to us, I let her catch me. My brother, being still stupid, ran away again.

It was the last time I saw him. Doris said he was my identical twin. Somewhere in North London there is another dog who looks

just like me—with the handsome profile of a small Alsatian and the elegant brown-and-gold flecked coat of a Staffordshire

bull terrier.

Doris was the first person who ever talked to me. Often I could not understand what she tried to say. But despite that, I

liked to listen to the noise she made. Now I understand much more—although I still have difficulty with complicated sentences,

especially if they are spoken in a conversational tone. I have a particular problem with subjunctives. But whenever someone

speaks to me, I feel happy. Conversation was, I suppose, the beginning of my corruption—or domestication, as humans call it.

Talk is now the noise I hear most often. Because of

that, the wolf within me sleeps—although he sometimes dreams. It was the wolf who kept me alive on the Paddington Recreation

Ground, but when he dreams, we go back together to the Siberian forest, not to north London. These days I would not swap my

bed against the radiator for a patch of frozen moss under a stunted tree. But I am glad that the wolf is still there, snoring

away inside me.

When Doris found me, the wolf was still wide awake and I had not yet learnt that a dog has to choose between the luxury of

family life and the excitement of the wild. So I expected to live with Doris for ever, listening to her talk when the mood

took me and fighting for my life the rest of the time. But Doris, who was old, thought I needed more exercise than she could

organize. So she found me a foster home in a flat a couple of roads away from her house. My new owners did their best to burn

off my energy But I didn’t settle down. Sheila—a “home-checker” for the Battersea Dogs’ Home—said I “lacked socialization

skills with both dogs and humans.” I was taken into canine care. Doris and her friends paid the fees.

The people who ran the dogs’ home kept me warm and well fed. But they did not talk to me. Indeed,

they did not talk to any of the dogs. That was not so bad for the others. They were only there for a week or two while their

owners were on holiday But I thought I would be there for ever. I lost my appetite and my ribs began to show. Even today,

if I think I am going to be left alone, I cannot concentrate on my breakfast.

Hoping somebody would adopt me, my beneficiaries put an advertisement in a dog magazine. It said I was “very clean.” That

was true. It was also insulting. There are much better things to say about me than that. A lady in Gloucester, who liked bullterrier

crossbreeds wrote to say she might adopt me. But when she saw my picture, I was so thin that she thought I was ill. You have

to be a saint to adopt a sick dog.

After a while, I was moved to another kennel in Surrey, where a family kept me—and several other dogs—for more or less nothing.

The owners took a special liking to me, perhaps because they were sorry I was so thin or perhaps because they realized what

a great dog I would become if someone gave me loving care. They fed me special treats and talked to me a lot. The other dogs

did not like me being the favorite. But the wolf inside me kept them in their proper place. I

began to grow and put on weight. In fact, I became too healthy for my own good.

I was a victim of the Dangerous Dogs Act. Families which might have adopted me were afraid I would grow into a pit bull terrier,

one of the dogs that policemen can take away and shoot. So I stayed at the Surrey kennel for months. Doris died. And I do

not know what would have happened to me had Doris’s friends not decided on one last advertisement.

Dogs are not supposed to be given as presents. We are for life, not Christmas. But She came to see me at the Surrey orphanage

and decided I was “a dog that a Yorkshireman would be proud to own.” The Man—who comes from Yorkshire—was not sure he wanted

to own any dog at all. He now denies it. But I happen to know that I spent two unnecessary extra weeks in Surrey while he

argued about the problems of keeping a dog in London and worried what would happen when he wanted to go to Italy for his holidays.

The solution to the second problem was, of course, perfectly simple. He doesn’t go to Italy any more.

However, the Man is not as stupid as his first reaction suggests. One day She brought me home. And as soon as he saw me, he

knew he wanted to keep me for

ever. I was already asleep, but he knelt down by the side of my bed and rubbed me behind the ears. He does that a lot. It

is one of his signs of affection. So I enjoy it whether my ears are itching or not. At first, I was not sure how we would

get on. I had not even begun to wrestle with the dilemma that all young dogs must face—the choice between independence and

comfort. The diary is an account of how I have balanced (not always with complete success) instinct and expediency, self-respect

and regular meals, independence and somebody’s voice to listen to when I feel sad or lonely.

Over the two years the Man and I have become friends. That is why I accept, with good grace, his disruptive habits and stood

by him when he was prosecuted after the incident with the greylag goose in St James’s Park. Until that day in the spring of

1996, I had taken it for granted that we would live for ever in peaceful obscurity. The goose changed all that. I have become

public property. Even today, the

Evening Standard

Londoner’s Diary telephoned to ask if I had been nominated for one of the “Dogs’ Oscars” and expressed bogus incredulity

when told that I was waiting for the Whitbread Prize for Literature for my autobiography.

There have, I admit, been moments when I have enjoyed my fame. I took especial pleasure in the occasion when he was accosted

in the street by a lady who told him, “I know what the dog is called, but I can’t remember your name.” But sometimes the newspapers

have gone too far. I would have tolerated their constant intrusion had they told the consistent truth. But they have changed

me from a dog into a brindle cliché. I want people to know what really happens as man and dog learn to live together by gradually

accepting each other’s limitations and acquiring each other’s characteristics. There is more to life than chasing postmen.

Other dogs may resent so intimate a description of the historic battle to reconcile pride in our nature with the comforts

of human civilization. To those whom I have offended, I offer my apologies and I express my profound gratitude to the Man

for his assistance in putting my diary on paper—though I think he may have invented one or two stories to make it more interesting.

Anyway, most of it is true. My earnest wish is that, by working with me on my diaries, he will have found some compensation

for his own literary disappointments. These days his frustration is most frequently demonstrated by the constant repetition

of

third-rate poetry In our early days he was—insensitively you may think—particularly addicted to a line from Oliver Goldsmith:

“Puppy mongrel, whelp and hound and cur of low degree.” I have learnt to live with such indignities.

I hope that my story will be an inspiration to young dogs everywhere. Do not think of it as a bark-and-tell expose. It is

the account of an odyssey which took a crossbreed orphan from living rough on a public park to the comfort and security of

South West London. Within a year of leaving the dogs” orphanage, I was accused (in the

Daily Telegraph)

of being so middle class that I slept on a bean bag. It was not true. But the accusation—by its source and its nature—illustrates

how far and how fast I have traveled. I hope you will enjoy my account of the journey.

Deliverance

In which Buster, a dog of spirit and fortitude, is saved from a life of want and degradation, and begins to experience both

the penalties and the privileges of domestication.

I think I shall like it here. There are no other dogs, but there is a Man who would like to be one. When I arrived he got

down on his hands and knees, and although he told me to stop licking his face, I knew he didn’t mean it. Tomorrow I shall

try chewing his ear. Thanks to my dominant personality and animal cunning, I may well become leader of this pack. And even

if I don’t, there will be real human beings to talk to me.

Everybody was very good about the vomit. The Man helped clean out the animal ambulance (a broken-down old van) and told the

driver that I must suffer from motion sickness as I didn’t seem to be the nervous

type. To be honest, I was terrified. Nobody had told me where I was going or what sort of people were going to look after

me. Although I look like one of those fighting dogs in the Sunday newspapers’ color magazines, I often feel very insecure.

I certainly don’t see myself doing ten rounds with a rottweiler. Whenever a skinhead came into the dogs” home, I sat at the

back of my kennel and tried to look like a Pekinese.