Butterfly Weed (45 page)

Authors: Donald Harington

But there is so much of what you have been learning that Colvin could not possibly have known: all the things that happened to Tenny on Brushy Mountain and in the sanatorium, all her thoughts and feelings that have come to us under her own point of view in the future tense. If I didn’t get any of this from Colvin, and I’m not just making it up, where does it come from? I wish I could give some “valid” explanation, such as that Tenny’s spirit visited me as I lay on that cot which had been her bed. Or that she will have told me all of this during the “visitations” when she comes to me if I close my eyes right.

But the truth will be that Tenny can not only tell, she can also tell.

At whatever point Tenny will have taken over the telling, and the “telling,” she will not only have made herself immortal but also have made her story not something which happened, or is happening, but will be happening, as long as she is still “around.” And believe me—or you know it, don’t you?—she’s very much around. Remember I told you how I can close my eyes to make someone disappear and be replaced by someone else? Don’t be offended, but I will be replacing

you

with Tenny, all the time. I will see her

now.

One afternoon Colvin and I will be sitting on the porch, and Rowena will be quitting for the day. As Rowena will walk down the porch steps and out into the road, she’ll give her fine hips a jauntier swing than usual, and when she’ll be out of earshot, I’ll banter with Doc, “Did you ever git any of that?”

Doc will chuckle, and will blurt, “Never had no need of it.”

“Oh?” I will say, and before I can stop myself will ask, “Because Tenny takes care of you every night?”

Doc’s mouth will fall open, and he will stare at me, and then his face will grow very red. I will not be able to “tell” if the red is embarrassment or anger. Maybe some of both. Then he will demand, “How’d you know that?”

“It’s part of the story,” I will observe.

“But goshdang ye, it aint no story that I ever tole ye!” he’ll declare. “Where’d you hear it?”

“Did you ever tell it to anyone?” I will challenge him. “Even Latha?” He will shake his head. “Then how could I have heard it anywhere?”

“Have you been sneaking into my diary?” he will demand.

“You never told me you kept a diary,” I will say.

“I don’t,” he will admit. “But where in blazes did you learn about what Tenny does at night…unless you’re just making a wild guess?”

Well sir, we will have gotten ourselves into quite a flap or row over this matter, and, as such things will, it will escalate until we’re hurling epithets at each other which we will both regret the next day. Quite possibly I will have known that my time at Stay More will have come to an end and unconsciously I will have been picking a quarrel with him in order to make the parting easier. But as it will turn out, we will even argue over his bill. He will refuse to present me a bill, and will accept nothing. I will insist upon paying at least for the medical care if not for all the room and board or “hospitalization,” but he will act as if my money is tainted and won’t touch it.

I will not even be able to recall my last words to him, as I will be putting on my hat and lifting up my knapsack. But I will think they were: “Don’t you see, Doc? She will still be telling all of it, and always will.”

We will keep in touch, sporadically, over the years, with postcards. Doc will never have been much of a letter-writer. I will learn over the years how he will continue his obsession with the Great White Plague. Not from him will I learn the story of how, during the Second World War, one day in the heat of August, Colvin will discover some of his free-ranging chickens acting sick, having trouble breathing. Still being a veterinarian himself from way back, he will take cultures from the chicken’s throats and after incubating the plates for several days he will observe cultures of actinomycetes developing. He will excavate the soil in which the chickens will have been scratching, and will find that the organisms are resident in the soil, and he will continue working with these cultures until he feels he has discovered enough to send them off to other scientists who are working on the problem, one of whom, named Selman Waksman, will convert Colvin’s cultures into a powerful antibiotic called streptomycin, and will receive the credit for having discovered it. Colvin will not have been interested in any credit, anyway. He will simply have wanted, with all his heart, to wipe out the Great White Plague. And his streptomycin will have done it.

Will it be time for you to leave, now? Yes, soon; I will have only two things essentially left to say: how Colvin himself will have gone to join his beloved Tenny in the Land of Telling, which you will possibly already have known. I will forget the year; perhaps it will have been as late as 1957. They will say, as they will never tire of saying wondrous things about Colvin U Swain, that he will have had an opportunity to have done something that he had not quite been permitted to do that day on those rounds in the St. Louis hospital so many, many years before: he will restore a dead man to life. You will wonder, anyone will wonder: if he will have been capable of it, why will he not have done it to Tenny thirty some years before? We will never know. We will know only that this man, who will be clinically dead, and will have been so for a great number of hours, will be resurrected by Colvin. We will not even bother with the man’s name. The man will have meant nothing personally to Colvin; just one more Stay Moron with a terminal disease. But Colvin will have always believed:

The patient need not mean anything whatsoever personally in order to receive the physician’s most devoted attention.

Anyway, the gods or Whoever will have been angry with Colvin for restoring life, because one day not long after, while he will have been walking fast to get out of a rainstorm, he will have been hit by a thunderbolt and reduced to a pile of ashes, just enough ashes to be placed in a cannister and interred beside Tenny at that double tombstone.

So much for Colvin. Recently, I will have written this simple note to Mary:

“Dear Mary Celestia: The

VA

people will attend to all the details of my burial—undertakers, coffin, grave diggers, etc. Even the flag on the coffin, the chaplain, and a government marker for a tombstone.

ALL FREE

.

If anybody asks you for money, call your lawyer. Wommack, isn’t it? You don’t have to do

ANYTHING.

If you don’t feel like going out to the National Cemetery,

Don’t Go.

I am sorry I have no money to leave you, Mary Celestia. I love you, as always. Vance.”

I will not know, of course, how much more time Tenny will grant me in this future tense of hers. I might well be able to stick around for a few more years, but I’d just as soon get on over to the Fiddler’s Green in the Land of Telling as soon as they will be able to make room for me on the Liar’s Bench. I tell you, when I reach the Land of Telling, I intend to tell ’em a thing or two!

But all that telling, whether we mean knowing or narrating, is as immaterial and fugitive as those breezes bearing Tenny’s song, or the imagined choiring of trees. Her future tense may never come to an end, but it will pause for now, with the realization that the only way she will ever be able to give shape and substance and heart to it will be to transmit it to me in such a way that I will be able to pass it along to you, and you will be able, one of these years, to turn it into novel, giving the reader two whole handsful of Tenny’s future tense.

Which is exactly what I will have done, for Tenny no less than for you. Good-bye, my boy. Godspeed.

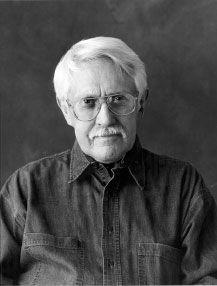

About the Author

Donald Harington

A

lthough he was born and raised in Little Rock, Donald Harington spent nearly all of his early summers in the Ozark mountain hamlet of Drakes Creek, his mother’s hometown, where his grandparents operated the general store and post office. There, before he lost his hearing to meningitis at the age of twelve, he listened carefully to the vanishing Ozark folk language and the old tales told by storytellers.

His academic career is in art and art history and he has taught art history at a variety of colleges, including his alma mater, the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, where he has been lecturing for fifteen years. He lives in Fayetteville with his wife Kim.

His first novel,

The Cherry Pit

, was published by Random House in 1965, and since then he has published eleven other novels, most of them set in the Ozark hamlet of his own creation, Stay More, based loosely upon Drakes Creek. His latest novel,

With

, was published in 2004. He has also written books about artists.

He won the Robert Penn Warren Award in 2003, the Porter Prize in 1987, the Heasley Prize at Lyon College in 1998, was inducted into the Arkansas Writers’ Hall of Fame in 1999 and that same year won the Arkansas Fiction Award of the Arkansas Library Association. He has been called “an undiscovered continent” (Fred Chappell) and “America’s Greatest Unknown Novelist” (Entertainment Weekly).

Table of Contents