Buttons (2 page)

Both sides of a button with a foil picture under glass on the front. The back mark reads ‘Registered Feb 11th. 1848 G.T.’

The industrial revolution of the eighteenth century introduced manufacturing processes which resulted in uniformity, replacing the unevenness and individuality of hand operations.

Some vogues in button ornamentation passed, never to return, whereas others became classics and were adapted only slightly by each generation. Clothing fashion may only guide us in the dating process because a favoured style can become a lifelong habit after newer fashions have been introduced. Small buttons were set close together to create a neatly fitted appearance to a bodice or sleeve. Large buttons could be used on loose, flowing styles as the width of the buttonhole provided a flexible dimension to the garment.

Ready-to-wear clothing has come to dominate the trade only since the Second World War. Before then personal tailoring from commercial establishments or home dressmakers allowed for a wide market for the button manufacturers. Buttons could be expensive items, often chosen with as much care as would be taken over a piece of jewellery, and selected for their individual appeal rather than because they matched a particular article of clothing. They were never thrown away, but kept in the button box, a tradition that persisted through many generations. Buttons with long shanks were generally intended for use on the thick cloth of gentlemen’s clothes. Once in the family button box, the original purpose of any type of button was forgotten. This recycling can present a collector with a very misleading provenance for a button.

‘Austrian tinies’, the collectors’ name for this type of late-nineteenth-century button, although they were also made elsewhere. All are

3

/

8

inch (1 cm), made up of decorative layers of various materials held together by the rim with a japanned back and metal shank.

Engraved pearl button, measuring 1½ inches (4 cm), with inset metal shank and silver-plated rim. The back mark of Firmin & Sons Ltd dates the button to after 1879.

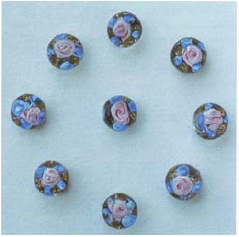

Nineteenth-century glass paperweight buttons with metal loop shank. The diameter of each is a quarter of an inch (7 mm).

Late-nineteenth-century lithographs.

Nineteenth-century pearl buttons. (Top row, left to right) Painted glass dome centre on grey pearl base; (next two) metal escutcheons on pearl. (Middle row, left to right) Steel tulip set into dyed pearl surround; dyed pattern and painted gold trim on pearl; silver inlaid into grey pearl. (Bottom row, left to right) Cut grey pearl with gold paint; cameo-cut dog’s head; glass centre on carved grey pearl.

Buttons date back as far as man’s use of a covering for his body. The hunter-gatherer of prehistory needed a fastening that held his goatskin warm and snug to his body and left his arms free to use weapons and tools. Buttons or button-like objects have been found in north European prehistoric sites, but the exact manner of their use is unknown.

Metal buttons are the items most commonly found by detectorists. Farming and transport involved large manual workforces until the mechanisation of the twentieth century. Their clothes had sturdy metal buttons. These finds are difficult to date owing to deterioration and their random nature. Until the industrial revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries metal buttons were costly and were consequently used and reused. Fashion was only for the rich and well-travelled classes.

Through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries buttons were made in small workshops. Every town would have had someone who included buttons as part of their production. Where there was a staple industry, with specific raw materials and skilled workers, specialist centres of button-making sprang up. Silk buttons were made in Leek (Staffordshire), Congleton and Macclesfield (Cheshire). Around Northamptonshire buttons were produced by knotting a thong of leather. Buttons decorated with steel studs were produced from used horseshoe nails in and around Woodstock, Oxfordshire. Buttons of national and international acclaim were produced in Dorset from linen thread stitched round bone discs and rings, a sizeable industry which was finally displaced in about 1850 by the introduction of machinery that made covered linen buttons. By the end of the eighteenth century Birmingham had become the centre of the button-manufacturing trade.

Metal-detector finds.

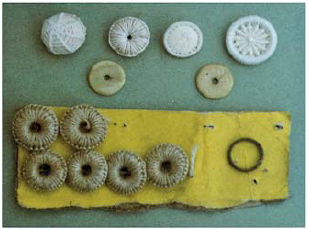

Dorset thread buttons, with ring, placed on the original yellow card, and the bone discs, above the card, used in their production.

Eighteenth-century dandy buttons, all measuring 1½ inches (4 cm). (Top and bottom rows) Hand-worked copper. (Middle row, left and right) Steel trimmed with diamante and pearl; (centre) Wedgwood cameo set in copper.

In the eighteenth century the industrial revolution resulted in the slitting mills and presses making excellent products of all varieties quickly and cheaply. It also created a new wealthy class of

nouveaux riches

with I money to spend on the excesses of fashion. Ladies’ clothes, for the greater part of the I century, were very elaborate. Buttons I featured on cloaks but were mainly for decoration on dresses or an alternative fastening to the more usual hooks and eyes or laces. The plain, simple empire line dominated fashion towards the end of the century. For men, no fashionable dandy was complete without his array of big buttons of carved pearl, cameos, miniature paintings, elaborate enamels, inlaid metals or cut steels, all about 1½ inches (4 cm) in size and exquisitely made.