C. J. Cherryh - Fortress 05

Read C. J. Cherryh - Fortress 05 Online

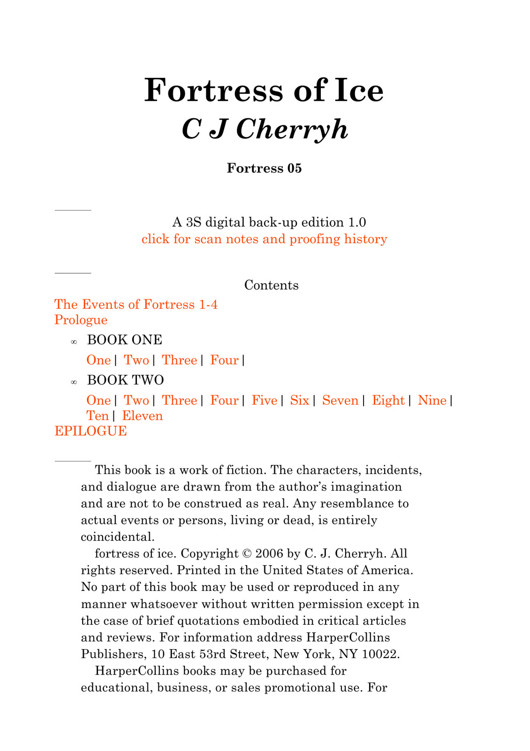

Authors: Fortress of Ice

C J Cherryh

Fortress 05

A 3S digital back-up edition 1.0

click for scan notes and proofing history

Contents

•

•

One

|

Two

|

Three

|

Four

|

Five

|

Six

|

Seven| Eight

|

Nine|

This book is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

fortress of ice. Copyright © 2006 by C. J. Cherryh. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022.

HarperCollins books may be purchased for

educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information please write: Special Markets Department, HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022.

FIRST EDITION

EOS is a federally registred trademark of

HarperCollins Publishers.

Designed by Sunil

Manchikanti

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cherryh, C.J.

Fortress of ice / C.J. Cherryh.—1st ed. p. cm.

ISBN-13:978-0-380-97904-2

ISBN-10:0-380-97904-7

1. Fantasy fiction.

PS3J53.H358 F725 2006 813'.54 22

2006043724

The Events of

FORTRESS IN THE EYE OF TIME,

FORTRESS OF OWLS, FORTRESS OF

EAGLES, FORTRESS OF DRAGONS

A VERY LONG TIME AGO, LONG BEFORE THE TIME OF MEN, GALASIEN RULED. ITS world was wide with trade and commerce, and sustained by wizardry.

But besides wizardry, there was native magic in the world. Far to the north, in the frozen wastes, the Sihhë existed. They might have been first of all. The Galasieni seemed to believe so.

The Sihhë were immortal. So the Galasieni believed.

And the Galasieni pursued those secrets of long life. One wizard, Mauryl Gestaurien, was very close. But his apprentice, Hasufin Heltain, wanted that secret, and seized power, a wizard-war that drove Mauryl to the Sihhë-lords themselves, asking help.

In the struggle that followed, all of Galasien went down in ruins.

One tower survived, Ynefel, where Mauryl defeated Hasufin and drove him into the Shadows.

When the dust settled, the faces of Galasien’s greatest wizards looked out from the walls of that ravaged tower, imprisoned in the stone, still living. Mauryl alone survived.

The five Sihhë-lords had come down, and ruled the land, as Men began to move into the west, and Sihhë blood mixed with that of Men.

For a number of centuries thereafter the land saw the rule of the innately magical Sihhë-lords, of whom there were five, and not all of whom were good, or kind.

Some Men thrived; some learned wizardry. Others rebelled, and plotted to seize power—hopeless as long as the five lords remained.

But in the passage of time the Sihhë-lords either perished, or retreated from the world. They left a thinner and thinner bloodline, half Sihhë, half Man.

Now Hasufin made his bid for life, stealing his way into a stillborn infant.

It was Selwyn Marhanen, a warlord under the High King Elfwyn Sihhë, who betrayed his lord and murdered him and all his house—while the court wizard, Emuin, killed Hasufin for the second time.

Selwyn Marhanen proclaimed himself king, in the kingdom that he called Ylesuin. He put down the old religion and all veneration of the Sihhë-lords, and established the Quinalt, the Five Gods. He built the Quinaltine in Guelemara, and perished, obsessed with nightmares and fear of damnation.

His son, Ináreddrin, succeeded him, in a reign distinguished by wars and internal disputes.

Ináreddrin had two sons, Cefwyn, the firstborn and heir, and Efanor, the son of Ináreddrin’s heart. Ináreddrin set his eldest son to oversee restive Amefel, the old Sihhë district, where assassins abounded, in fondest hope of having him die and Efanor inherit.

Magic was moving again, subtly, but old Mauryl saw it coming.

Locked away at Ynefel among his books, he nevertheless watched over the world, and he became more and more aware that his old enemy Hasufin, dead and not dead, had found his way back from his second death.

Feeling mortality on him, Mauryl created a Summoning, a defender, a power to oppose Hasufin, but his weakness—or in the nature of magic— things went awry. What he obtained was Tristen, bereft of memory.

Hasufin indeed brought Mauryl down, but missed Tristen, who wandered into the world and found himself in Amefel, a guest of Cefwyn Marhanen.

Hasufin’s power moved against Cefwyn, against the Marhanen, attempting to stir up trouble in Amefel—but the seeds of discontent in Amefel were the old loyalties to the Sihhë-blood kings—a bloodline which thinly survived in Amefel, in the house of Heryn Aswydd.

There was, ironically, one other in whom it ran very strongly: it was Tristen, who had become Prince Cefwyn’s friend.

King Ináreddrin died in an ambush Heryn Aswydd arranged.

That meant Cefwyn became king, and he hanged Heryn Aswydd—but he spared the lives of Heryn’s twin sisters, Orien and Tarien, both of whom had been Cefwyn’s lovers—and one of whom, which he did not know, was with child. He married the Lady Regent of Elwynor, an independent kingdom which still honored the traditions of the lost Galasieni, and she produced a legitimate son.

Tristen, gathering more and more of his lost memories, stood by Cefwyn, to the resentment of Cefwyn’s own people—even when Cefwyn’s victory in a great battle at Lewen Field, in Amefel, drove Hasufin from the world in a third defeat.

By now Tristen was known for much more than a wizard: people in the west openly called him Tristen Sihhë, and all of Elwynor and Amefel would have been glad to proclaim Tristen High King and depose Cefwyn. Emuin, Cefwyn’s old tutor, advised Cefwyn to be careful of that young man and never to become his enemy—and Cefwyn heeded the old wizard’s advice. He bestowed arms on Tristen, the Sihhë Star, long banned, and would have made him Duke of Amefel.

Hasufin, however, was not done: he used the Aswydd sisters—one of them the mother of Cefwyn’s bastard son. In the end, Tarien, her baby taken from her, was imprisoned in a high tower, spared her sister’s fate by Tristen’s intercession.

And in years that ensued, Cefwyn regarded Tristen as a brother, and leaned on his advice and Emuin’s.

But Emuin left the world, and Tristen himself lived in the world only as long as Cefwyn truly needed him: his presence roused too much resentment from Cefwyn’s people, the eastern folk of the divided kingdom. He set things in order in Amefel, saw a good duke in power over that land, and retreated increasingly into Mauryl’s haunted tower.

Cefwyn’s queen now had a son, an heir for Ylesuin, and then produced a daughter, who would inherit her own Regency of Elwynor. In these two children of loving parents, east and west were united, and peace settled on the land for the first time since Sihhë rule.

The bastard son lived happily enough in rural Amefel, foster brother to old Emuin’s former servant. The world went back to its old habits, and forgot, for a few years, that its peace was fragile.

SNOW CAME DOWN, LARGE PUFFS DRIFTING ON A GENTLE

WIND, WAFTING ABOVE the stone walls of the courtyard. Snow fell on dead summer flowers, on the stones of the broken walls, a fat, lazy snow for a quiet winter’s afternoon.

Tristen watched it from the front doors of the ancient keep, walked out and let it fall onto his hands, let it settle in his hair and all about his little kingdom. The clouds above were silken gray, so far as the great tower of Ynefel afforded him a view above the walls, and the leaves, clinging to dry flower stems, regained a moment of beauty, a white moment, remembering the summer sun.

He kept a peaceful household in the grim old fortress of Ynefel, with Uwen and his wife—Cook, as she had been when Uwen married her, and Cook she still liked to be—though her real name was Mirien. They fared extremely well, never mind the haunts and the strangeness in the old keep, which Cook and Uwen had somewhat, though haphazardly, restored to comfort.

The snows had come generously this winter, good for next year’s crops, of which Ynefel had none but Cook’s herbs and vegetables, and for good pasturage, of which it had very little, cleared from the surrounding forest. This snow brought a quiet cold with it, no howling wind, only a deep, deep chill that advised that the nights would be bitter for days. The Lenúalim would continue to flow along under the ancient bridge, collecting a frozen edge of ice up against the keep walls, possibly freezing over, but that was rare.

Though it would be well, Tristen thought, to take care of the rain barrel today, bring the meltwater they had gathered into the scullery and move the barrel in, before nightfall.

A lord, a king, could do that damp task for himself quite handily, but Cook would likely send her nephew to do the chore, in her notion of propriety. Uwen would be in the thick of the weather by now, doing his work up on the hill pasturage, bringing hay up to the horses and the four goats—a little spring flowed there, assuring that the animals had water in almost all weather. Cook would be fussing about down in the cottage, stuffing cracks, being sure she had enough wood inside the little house that flanked the keep: easiest to have that resource inside, if the snow became more than a flurry, and there was, Tristen thought, certainly the smell of such a snow in the air.

So, well, what had a lord to do, who had only three subjects?

He could let the snow carry his thoughts to his neighbors across the river, beyond Marna Wood. He could stand here, missing old friends today, with his face turned toward the gates that so rarely opened to visitors. He knew a few things that passed in the land, but not many. He knew that Cefwyn queried him; he answered as best he knew, but he thought less and less about the world outside the walls, beyond the forest. He wondered sometimes, and if he wondered, he could know, but he rarely followed more than the thread of Cefwyn’s occasional conversation with him, a warm, friendly voice. He was reluctant, otherwise, to cast far about, having no wish to trouble old and settled things in the land.

Occasionally, in summers, he entertained visitors, but lately only two, Sovrag and Cevulirn, who came as they pleased, usually toward the fading of the season. Emuin—Emuin, he greatly missed.

Emuin had used to visit, but Emuin had ceased to come, and drew a curtain over himself. Whether his old mentor was alive or dead remained somewhat uncertain to Tristen—though he was never sure that death meant the same thing to Emuin as to other Men.

Uwen traveled as far as Henas’amef from time to time, with Cook’s boy. Uwen reported that Lord Crissand fared quite well in his lands, and from Crissand Uwen gathered news from the capital of Guelemara, where Cefwyn ruled. The queen had had a daughter this fall, so Uwen reported, and that family was happy. It was good to hear.

He longed to see the baby. He so greatly longed to see Cefwyn…

to be in hall when the ale flowed and the lords gathered in fine clothes, to celebrate the return of spring—he might go if he chose.

But it was not wise. It was not, in these days, wise. He had fought the king’s war. He had settled the peace.

He had been a dragon.

He could not forget that, and in that memory, he stayed to his ancient keep, hoped for the years to settle what had been unsettled in those years, and let his friends live in peace.

SNOW FELL THICKLY ON GUELEMARA, GRAY CLOUDS

SHEETING ALL THE HEAVENS and snow already lay ankle deep in the yard, but the threatening weather had not brought quiet to the courtyard. His Royal Highness Efanor, Prince but no longer heir of Ylesuin, tried manfully to concentrate on his letters, while young lords laid on with thump and clangor below the windows, shouting challenges at one another and laughing. Efanor penned delicate and restrained adjurations to two jealous and small-minded priests of the Quinaltine, while sword rang against sword—fit accompaniment to such a letter, in Efanor’s opinion.

The clergy was in another stew, a matter of a chapel’s income and costs, a niggling charge of error in dogma on the one hand and finance on the other hand—when, among priests, was it not?—and ambition in another man: the latter was, in His Royal Highness’s opinion, the real crux of the matter.