Read Caesar. Life of a Colossus (Adrian Goldsworthy) Yale University Press Online

Authors: Adrian Goldsworthy

Caesar. Life of a Colossus (Adrian Goldsworthy) Yale University Press (77 page)

431

XX

Cleopatra, Egypt

and the East,

Autumn 48–Summer 47 BC

‘Caesar also had affairs with queens . . . most of all with Cleopatra, with whom he often feasted until first light, and he would have sailed through Egypt on her royal barge almost to Aethiopia, if his army had not refused to follow him.’ –

Suetonius, late first/early second century AD.

1

‘Cleopatra . . . was a woman of surpassing beauty, and at that time, when she was in the prime of her youth, she was most striking; she also possessed a most charming voice and a knowledge of how to make herself agreeable to every one. Being brilliant to look upon and to listen to, with power to subjugate every one, even a love-sated man already past his prime, she thought that it would be in keeping with her role to meet Caesar, and she reposed in her beauty all her claims to the throne.’ –

Dio, early third century AD

.2

Caesar followed up his success at Pharsalus with his usual vigorous pursuit and arrived in Alexandria just three days after Pompey’s murder. It was important to complete the victory by preventing the enemy from regrouping. Pompey’s skill, reputation and huge array of clients made him still the most dangerous opponent even after his defeat, and Caesar had focused his main attention on hunting down his former father-in-law. He travelled quickly, taking with him only a small force. At one point he came across a far larger squadron of enemy warships, but such was his confidence that he simply demanded – and promptly received – their surrender. Caesar paused for a few days on the coast of Asia, settling the province and arranging for the communities, especially those that had strongly supported the Pompeians, to supply him with the money and food he needed to support his ever-growing armies. At this point news arrived that Pompey 432

Cleopatra, Egypt and the East, Autumn 48–Summer 47 bc

was on his way to Egypt and Caesar immediately resumed the hunt, taking with him some 4,000 troops and reaching Alexandria at the beginning of October. Almost immediately he learned of Pompey’s death, and soon afterwards the latter’s signet ring and head were presented to him by envoys of the young king. Caesar wept when he saw the first and would not look at the second. His disgust and sorrow may well have been genuine, for from the beginning he had taken great pride in his clemency and willingness to pardon his enemies. Whether Pompey would have accepted this is another matter, having earlier in the year declared that he had no intention of living on indebted to ‘Caesar’s generosity’. A cynical observer might say that it was very convenient for Caesar to be able to transfer to foreign assassins the guilt for killing one of the greatest heroes in the history of the Republic. Yet in the past there does seem to have been some genuine affection between the two men as well as political association. Even when they came to see each other as rivals, it is extremely unlikely that Caesar ever wanted to kill Pompey. His aim was to be acknowledged by everyone, including Pompey himself, as Pompey’s equal – and perhaps in time as his superior. A dead Pompey was far less satisfying.3

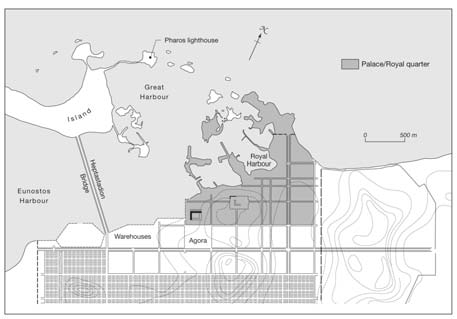

Nevertheless, the murder made it clear that the local authorities were keen to please the newcomers, and Caesar decided to land with his troops. With him were the

Sixth

Legion, reduced by constant campaigning to under 1,000 men, and one of Pompey’s old formations that had now been renumbered the

Twenty-Seventh

and mustered some 2,200 legionaries. Supporting these were some 800 auxiliary cavalry, at least some of whom were Gauls and others Germans. It is possible that this was the bodyguard unit that had accompanied Caesar in the recent campaigns. It was not an especially strong force, but Caesar did not expect to face serious opposition. He disembarked and marched to take up residence in one of the palaces in the royal quarter of the city. As consul, he was preceded by twelve lictors carrying the fasces which symbolised his

imperium

as a Roman magistrate. The sight provoked a hostile reaction from the royal troops in the city and from many of the Alexandrians. The Romans were jeered and over the next few days a number of legionaries caught alone in the streets were attacked and killed by mobs. Caesar had stumbled into the middle of Egypt’s own civil war and would soon be besieged and fighting for his life, completely out of touch with events in the rest of the Mediterranean. Before describing what became known as the Alexandrian War, it is worth pausing to consider Egypt in the fading years of the Ptolemaic dynasty.4

433

CIVIL WAR AND DICTATORSHIP 49 – 44 BC

Ptolemaic Egypt and its Queen

Alexander the Great had taken Egypt from the Persians in 331 BC, founding Alexandria that same year – one of a number of cities bearing his name, although in time it outstripped all the others. When he died his massive empire was torn apart by his generals as they struggled to carve out kingdoms of their own. One of the most successful was Ptolemy, son of Lagus, who became Ptolemy I

Soter,

or ‘saviour’, and took Alexandria in Egypt as his capital, even managing to divert Alexander’s funeral cortege so that the body of the great conqueror was interred in the city. The dynasty Ptolemy founded would rule for almost three centuries, controlling an empire that at times included not just Egypt, but also Cyrenaica, Palestine, Cyprus, and parts of Asia Minor. Its extent varied, outlying territories being lost to rebellion or the renewed vigour of the other great successor kingdoms of Antigonid Macedonia and the Seleucid Empire. The balance of power between the three rivals fluctuated over the years, but by 48 BC both of the others had gone. Macedonia had become a Roman province in 146 BC, while Pompey had deposed the last Seleucid king in 64 BC and taken Syria under Roman rule. The Macedonians and Seleucids had chosen to fight Rome and had lost. In contrast the Ptolemies formed an alliance with the Roman Republic even before it began to extend its power into the region. The kingdom survived, but it gained few benefits from Roman expansion and during the second century BC this was a contributory factor in its steady decline. As important were the almost unending dynastic struggles within the royal family. Ptolemy II had married his sister, inaugurating a tradition of incestuous marriages – brother to sister, nephew to aunt and uncle to niece – which persisted to the end of the dynasty. Such unions, broken only by occasional marriages to foreign, usually Seleucid princesses, prevented the aristocratic families from gaining claims to the throne. The price was to make the pattern of succession very unclear. Factions grew up surrounding different members of the royal family, all eager to advance them to become king or queen and so gain influence as their advisor. Civil wars were frequent, and over time it became more and more common for Rome to act as arbiter, formal recognition by the Romans helping greatly to legitimise a monarch’s rule. The kingdom’s independence was gradually eroded.

Egypt remained very wealthy. In part this was through trade, Alexandria being one of the greatest ports in the ancient world, but more than anything else it rested on agriculture. Every year the Nile flooded – as it still did until the construction of the Aswan dam. When the water receded the farmers were 434

Cleopatra, Egypt and the East, Autumn 48–Summer 47 bc

able to sow their seeds in fields rendered very fertile by the moisture. The scale of the annual inundation varied and, as in the Book of Genesis, there could be years of famine as well as years of plenty, but in general the harvest produced a substantial surplus. Many centuries before the unrivalled fertility of the Nile valley had allowed the civilisation of ancient Egypt to flourish and create its awesome monuments. More recently it had made the region an attractive conquest for the Persians and after them the Macedonians. The power of the Ptolemies was always based firmly on Egypt. Through a sophisticated bureaucratic machine, much of it inherited from the earlier periods, they were able to exploit this productivity. An important component within the system was the temples – many of which preserved the worship and rites of the old Egyptian religion and were little influenced by imported Hellenic ideas. The temples were major landowners, but also centres for industry and craft, and had privileged status, exempting them from most taxation. Roman visitors to Egypt were amazed by the fertility and wealth of the country, as much as they claimed to have been shocked by the intrigue and opulence of the royal court. By the first century BC Egypt seemed to offer the prospect of massive wealth to a number of ambitious Romans.5

The career of Cleopatra’s father illustrates both the instability of Egyptian politics and its ever more blatant dependence on Rome. He was Ptolemy XII, illegitimate son of Ptolemy IX and (most probably) one of his concubines. His father had become king in 116 BC when his mother chose him as joint ruler and husband, but was later rejected in favour of another brother, the massively obese Ptolemy X. He eventually returned to oust them both by force and remained on the throne until his death at the end of 81 BC. Ptolemy IX was succeeded by his nephew Ptolemy XI, who was taken as husband and consort by his stepmother, promptly murdered her and was himself in turn assassinated soon afterwards. Ptolemy XII was then recognised as King of Egypt by Sulla. He styled himself the ‘New Dionysus’ (Neos Dionysus), but was often known less flatteringly as Auletes or the ‘flute player’ – some would argue that oboe player would probably be a better translation, but the other version is more commonly used. In 75 BC rival claimants to the throne had gone to Rome to lobby the Senate, but eventually left without achieving anything. Yet the wealth of Egypt remained a great temptation to ambitious Romans. A decade later Crassus hoped to use his censorship to annex Egypt as a province, probably on the basis that Ptolemy X had bequeathed it to Rome in his will, a copy of which had been sent to the city. As noted earlier, Caesar was credited with similar plans (see p.114–5). Neither man succeeded, but as consul in 59 BC Caesar did share with Pompey the staggering 6,000

435

CIVIL WAR AND DICTATORSHIP 49 – 44 BC

Alexandria

talent bribe that Ptolemy XII promised as payment for having him formally acknowledged as ‘friend and ally’ of the Roman people. Collecting this sum proved difficult and probably contributed to the uprising that forced him to flee from Egypt in the following year. He went to Rome in the hope of winning the support that would restore him to power, and it is just possible that he took his eleven-year-old daughter Cleopatra with him. The issue became a fiercely contested one, since many craved the chance of a campaign in Egypt and the rewards likely from a grateful king. In 57 BC the consul Publius Lentulus Spinther – the same man who later surrendered to Caesar at Corfinium – was given the task of restoring Ptolemy to the throne, but political opponents managed to ‘discover’ an oracle that was interpreted as meaning that he would not be allowed an army for this task. Eventually, in 55 BC, Gabinius took it upon himself to do this, inspired by Auletes’ promise of 10,000 talents. In the event the bulk of the money could not be found, and Gabinius returned to trial and condemnation at Rome, before reviving his fortunes by joining Caesar in 49 BC.6

After his expulsion in 58 BC, Ptolemy’s daughter Berenice IV had been made ruler, at first with her sister the elder Cleopatra VI as co-ruler, but following the latter’s death she married a son of Mithridates of Pontus, a connection that only increased the pressure on Rome to act. On his return 436

Cleopatra, Egypt and the East, Autumn 48–Summer 47 bc

Auletes had Berenice killed, but his efforts to raise the money owed to Gabinius and other Roman creditors were generally unsuccessful. He remained deeply unpopular, but even greater hatred grew up for the Romans who had backed him and who now wished to exploit the country so shamelessly. Alexandria in particular witnessed frequent rioting and attacks on Romans. In 51 BC Auletes finally died, leaving the throne jointly to his third daughter, the seventeen-year-old Cleopatra VII, and his elder son, the tenyear-old Ptolemy XIII. He had already sent a copy of his will to be kept at Rome, a measure that made clear his acknowledgement of the Republic’s power. Brother and sister were promptly married in the usual way. In spite of her youth, Cleopatra was evidently already a forceful character, and decrees issued at the beginning of her reign make no mention of Ptolemy. The boy was not old enough to assert himself, but his ministers and advisors, led by the eunuch Pothinus and the army commander Achillas, soon began to oppose his older sister. Alexandria had been turbulent for some time. A series of poor harvests added to the discontent of the wider population – the Nile was at its lowest recorded level in 48 BC. In 49 BC Pompey sent his son Cnaeus to Egypt to secure support for the forces he was gathering in Macedonia. Cleopatra welcomed him – much later there were rumours of an affair, but this may well be no more than gossip or propaganda – and sent a contingent of the soldiers left behind by Gabinius along with fifty ships. This compliance with the Romans was sensible, given their power and the debt of her father to Pompey, but it may well have been unpopular. Controlling much of the army, and with a good deal of support from the Alexandrians, the regents were able to drive Cleopatra from the country. The queen took refuge in Arabia and Palestine, and was supported by the city of Ascalon – one of the former Philistine cities from the Old Testament period, which in recent centuries had usually been under Ptolemaic control. By the summer of 48 BC she had gathered an army and had returned to reclaim the throne. This force and those loyal to her brother were warily shadowing each other from opposite sides of the Nile Delta when Pompey, and then Caesar, arrived in Egypt.7