Cambodia's Curse (25 page)

Authors: Joel Brinkley

Sam Nhea sits with his two barely-conscious children, one of whom is out of frame, in the Andong evictee camp.

Police man a checkpoint in Pursat Province where they stop drivers and demand bribes.

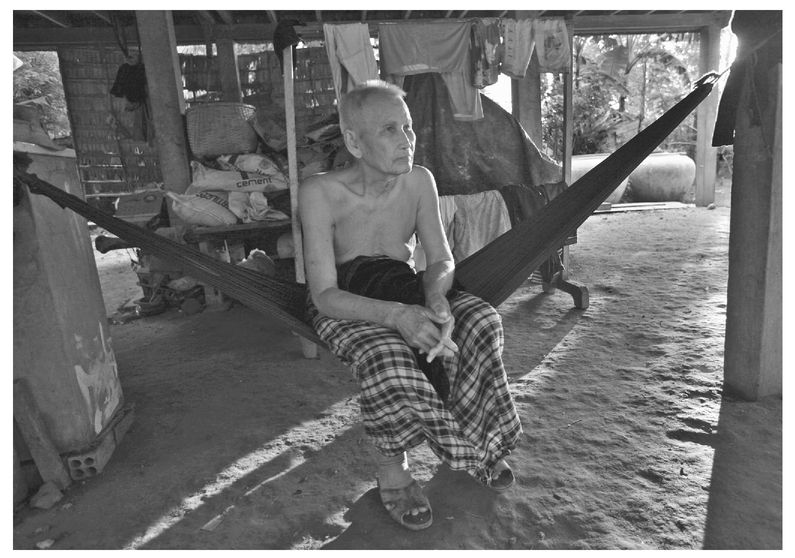

Pol Pot’s younger brother, Saloth Nhep, 84, reflects on his life a few months before he died.

Youk Chhang, director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, sits before a shrine holding skulls of Khmer Rouge victims.

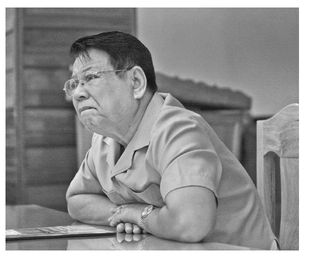

Chhay Sareth, Pursat Province council chief, complained about the province’s corrupt prosecutor.

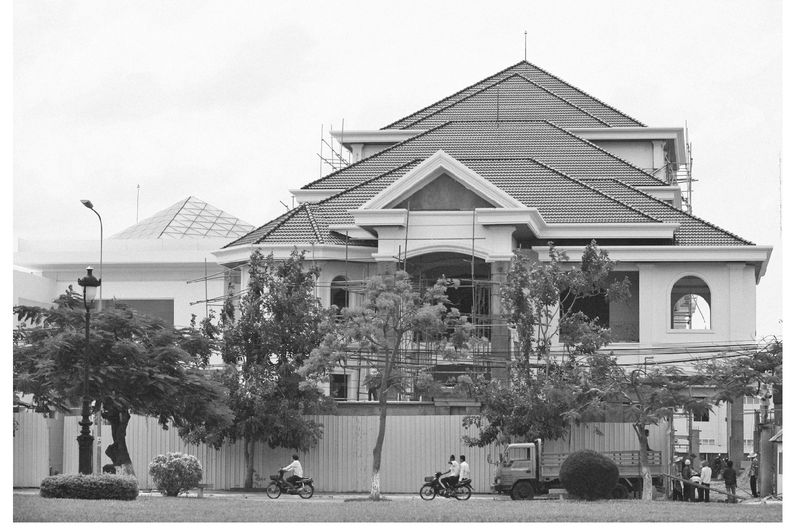

Prime Minister Hun Sen’s new mansion, theoretically built with money from his salary, has a heliport on the roof.

Deputy Prime Minister Sok An’s house is the size of a small hotel.

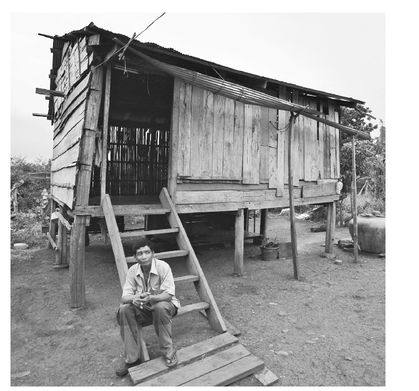

Millions of Cambodians live in houses much like Mith Ran’s simple abode.

CHAPTER EIGHT

I

t’s hard to overstate how important trees are to Cambodians. Since the beginning of human habitation of this bucolic state, people have built their homes from tree trunks, limbs, and branches—even making use of the leaves. They’ve taken food from the fruit trees, burned tree limbs to cook their food, lived in the shade of trees as protection from the brutal heat, tapped tree resin to seal the hulls of their fishing boats, and much more. That is why so many people looked on with genuine distress as the Khmer Rouge, after their defeat, denuded northwestern Cambodia of vast forests and sold the lumber to Thai generals.

t’s hard to overstate how important trees are to Cambodians. Since the beginning of human habitation of this bucolic state, people have built their homes from tree trunks, limbs, and branches—even making use of the leaves. They’ve taken food from the fruit trees, burned tree limbs to cook their food, lived in the shade of trees as protection from the brutal heat, tapped tree resin to seal the hulls of their fishing boats, and much more. That is why so many people looked on with genuine distress as the Khmer Rouge, after their defeat, denuded northwestern Cambodia of vast forests and sold the lumber to Thai generals.

These weren’t just any old trees. Cambodia is fortunate to be home to tropical trees that produce some of the world’s most beautiful woods. Some provide exquisite-looking lumber that in appearance offers a rich, unique coloration. It’s roughly a cross between walnut and mahogany with an attractive meandering grain. Some feature a blondwood stripe, maybe three-quarters of an inch wide, that twists and turns through the tree. Cambodians call the lumber from these trees “luxury wood.” It is prized and quite valuable. As a mark of status, senior government ministers place massive luxury-wood chairs in their

offices. Intricate designs are carved into the six-foot-high seat backs, and the chairs are finished with a high-gloss varnish so they sparkle.

offices. Intricate designs are carved into the six-foot-high seat backs, and the chairs are finished with a high-gloss varnish so they sparkle.

Shortly after taking office in 1993, Ranariddh and Hun Sen sent that letter to the Thai government saying they alone were authorized to sell this lumber, through the Ministry of Defense. In the following years they sold what the government called “concessions” to friends and cronies—dozens of them, involving thousands of acres of forest. The buyers would cut down all the trees, haul the lumber away, and then leave behind vast empty fields dotted with ugly stumps. (You can only guess into whose pockets the concession payments went.) And once Hun Sen and Ranariddh designated the Defense Ministry as the state’s only legitimate tree broker, its own officers began freelancing in the forests, making their own fortunes by cutting down thousands of trees.

Through the 1990s all manner of Cambodians plunged into this orgy of deforestation. Patrons to roadside beer bars in Pailin, near the western border, sat in luxury-wood chairs pulled up to table tops made from one solid slab of this wood, four feet wide, six feet long—and seven inches deep. A fifteen-dollar-a-night guesthouse in Battambang featured massive luxury-wood beds with heavily carved headboards, eight feet tall. One of those blond stripes coursed through the footboard, and each of these beds weighed well over 1,000 pounds.

Cambodia’s trees were fast disappearing. But early in the 2000s the World Bank office in Phnom Penh made saving the remaining forests a major priority. The bank was among the nation’s largest foreign-aid donors and was also quite influential within the donor community. So when bank officers urged Hun Sen to hire a company to monitor the forests, he agreed—and even accepted the bank’s choice for the job, a British advocacy organization named Global Witness. The group described its mission as follows: “Global Witness exposes the corrupt exploitation of natural resources and international trade systems, to drive campaigns that end impunity, resource-linked conflict, and human rights and environmental abuses.”

Global Witness investigators had already worked in Cambodia, in 1995, and had written a report about Khmer Rouge timber sales. Boasting about this later, the group wrote, “In 1995, within five months of commencement, our very first campaign closed the Thai-Cambodia border to the $20 million per month timber trade between the Khmer Rouge and Thai logging companies.” Now, Global Witness’s take-noprisoners investigators were doing what they best liked to do—under government contract! At the same time, in Phnom Penh, World Bank officers were working to close down the government’s utterly corrupt land-concession schemes. The two were promising to shut the lumber business down.

In time Ian Porter, the World Bank’s country director, said he had seen progress. “Forest concessions have been suspended,” he said, “public disclosure has improved, and environment and social-impact assessments have been used for sustainable forestry management plans.” But as it turned out, that was far from the end of the story.

N

ow that Hun Sen and his Cambodian People’s Party controlled all of the government agencies that mattered, the ones that could make money, ministers and their allies showed just how imaginative and innovative they could be. They certainly weren’t thinking up clever new ways to help their constituents—by most measures the health and welfare of Cambodians were at best stagnant. Instead, a local human-rights group uncovered a scandal in 2001 that showed how little regard government leaders actually accorded their own people, especially their children.

ow that Hun Sen and his Cambodian People’s Party controlled all of the government agencies that mattered, the ones that could make money, ministers and their allies showed just how imaginative and innovative they could be. They certainly weren’t thinking up clever new ways to help their constituents—by most measures the health and welfare of Cambodians were at best stagnant. Instead, a local human-rights group uncovered a scandal in 2001 that showed how little regard government leaders actually accorded their own people, especially their children.

At this very time, in Mai Sai, Thailand, mothers were selling their twelve-year-old daughters to slave traffickers who subjected them to a hellish life as prisoners in brothels, karaoke bars, and strip joints. Sometimes those Thai traffickers had to pay off local police, but there was no indication that government officials in Bangkok were involved;

sometimes they even arrested traffickers. In Cambodia, however, very senior officials in the Interior Ministry and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs were directly profiting from the baby trade.

sometimes they even arrested traffickers. In Cambodia, however, very senior officials in the Interior Ministry and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs were directly profiting from the baby trade.

Other books

The Breakup by Brenda Grate

Will the Real Abi Sanders Please Stand Up? by Sara Hantz

Clockwork Twist : Waking by Emily Thompson

The Final Wish by Tracey O'Hara

Broken World Book Two - StarSword by Southwell, T C

The Billionaire's Burden (Key to My Heart #2) by Ella Cari

The Fix Up (First Impressions #1) by Tawna Fenske

Irregular Verbs by Matthew Johnson

Winterveil by Jenna Burtenshaw