Canada Under Attack (8 page)

My antagonist hast wisely shut himself up in inaccessible entrenchments, so that I can't get at him without spilling a torrent of blood, and that perhaps to little purpose. The Marquis de Montcalm is at the head of a great number of bad soldiers and I am at the head of a small number of good ones, that wish for nothing so much as to fight him; but the wary old fellow avoids an action doubtful of the behaviour of his army.

16

Wolfe rose from his bed to pitch a plan of attack; his junior officers immediately dismissed it and, dejected, he returned to his bed. The officers devised a plan of their own that called for an invasion 64 kilometres upriver and would allow the British to cut-off French supply lines. They hoped that would finally draw Montcalm into a battle. Wolfe initially agreed to the plan, which called for the troops to land near Pointe-aux-Trembles, but heavy rains first delayed then prevented the landing entirely. While the troops regrouped, Wolfe changed the plan. He had spied another potential location for a landing: the cliffs at Anse-au-Foulon. It was, in many ways, a much riskier plan than the one proposed by his officers. For one thing, there were massive cliffs that the armies would be forced to climb before they could make the battlefield. Another potential problem was that landing at Anse-au-Foulon would put the British troops between the two most heavily manned French positions. However, landing there would allow Wolfe to greatly enhance his numbers with easy access to the troops holding both Pointe-Lèvy and Ãle d'Orléans.

With little fanfare, the navy began to move Wolfe's troops upriver. At dusk on the evening of September 12, one of the British ships began to fire on the French troops at Bougainville, drawing French attention away from Anse-au-Foulon. Fortune was finally smiling on Wolfe. A French supply ship was expected and orders were given to do nothing to jeopardize its safe arrival in Quebec City. Although the supply ship never arrived, most of the French troops did not know and would follow their orders, exercising an abundance of caution in their dealings with the English in fear of harming their own supply ship. As darkness fell, Wolfe and his troops slipped into boats and schooners and silently began to row toward shore.

A French sentry challenged the boats and a fast thinking officer quickly answered him in French. When they were challenged again, the same officer told them to shut up or “you'll give us away to the English.” As his boat bumped up against the shoreline, Wolfe leapt onto the beach, the first man to do so, and quietly ordered the men behind him to take the path to the guard post at the top of the cliff. Luck intervened there as well. The officer in charge of the sentries had let many of his men return home to help with the harvest. The remainder were quickly overwhelmed by the English soldiers, except one who escaped to sound the warning.

Neither Montcalm nor de Rigaud believed the news when it was brought to them. The English could not possibly be launching an invasion now, and certainly not where the sentry claimed they had landed.

As we came into la Canardière courtyard, a Canadian arrived from the post of Mr de Vergor, to whom the Anse-au-Foulon post had been entrusted truly at the worst of times. This Canadian told us with the validation of undisputed fear that he was the only one who had escaped and that the enemy was on top of the hills. We well knew about the difficulty of forcing our way through this place even when it was barely defended, so that we did not believe a word of the account of a man whose head, we thought, had been turned by fear.

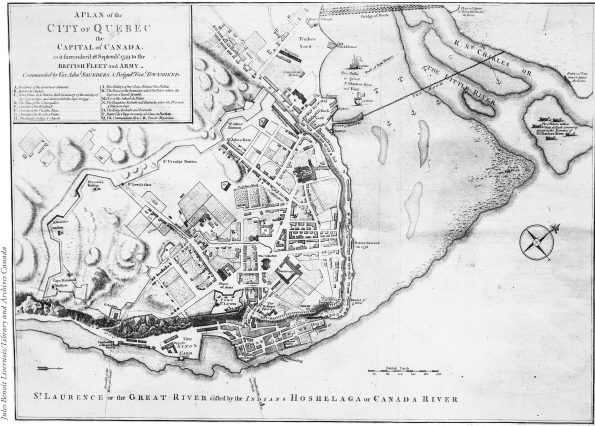

A Plan of Quebec City at the Time of the Siege, 1759.

A sceptical Montcalm hurried to a vantage point overlooking the Plains of Abraham and saw hundreds of redcoats spilling over the edge of the cliffs and onto the flat, hard ground beyond the city.

As Wolfe massed his troops at the edge of the Plains of Abraham, and handfuls of rangers captured surrounding houses, Montcalm considered his options. He could wait for reinforcements to arrive from Bougainville. He had barely 3,000 troops on hand, and most of those were militia. He could not strip the city of its defenders, but on the other hand there did not appear to be too many British soldiers. He also could not afford to wait. As he explained, “We cannot avoid the issue. The enemy is entrenched; he already has two pieces of cannon. If we give him the time to establish himself, we'll never be able to attack him with the few troops we have. Is it possible that Bougainville doesn't know this?”

17

Unfortunately for Montcalm, the rough terrain hid many of the invaders. He made the call to advance immediately on the British. The difference between the two armies was never as obvious as it was on the Plains of Abraham. Montcalm's inexperienced militia ran forward in a disorganized charge, shooting wildly. Few of their bullets found their intended targets. Wolfe's experienced troops advanced slowly in a solid red line, holding their fire until they neared the French troops and then, in unison, they took careful aim and fired their weapons. The volley hit the French line like a devastating tidal wave. The French quickly broke ranks and began an equally disorganized retreat to the fort.

Wolfe was in the midst of his men, urging them on. One of the first volleys launched by the French caught him in the wrist. Another caught him in the stomach, but he forced himself forward. Almost at the same time, Montcalm was struck in his side by a British musket and he was carried from the field. Wolfe, mortally wounded, finally fell to the ground. An aide tried to ease his pain by telling him of the battle's progress. When the aide announced that the enemy was routed, Wolfe is said to have proclaimed, “[N]ow I can die in peace.” He rolled over on his side and died shortly thereafter. Montcalm would die the next day of the injuries he had sustained early in the battle.

Within the city, other leaders met to discuss whether to defend or surrender. Montcalm's aides urged them to fight on. They had nearly 13,000 men, a force far larger than that commanded by the British. But the city fathers and many of the officers had lost their general; they were sick of war and far less confident in the unseasoned troops. They decided to sue for peace. The siege of Quebec was over.

CHAPTER FOUR:

THE FOURTEENTH COLONY

While Wolfe's career ended on the Plains of Abraham, the career of one of his most trusted lieutenants began there. Guy Carleton had been the officer to whom Wolfe entrusted construction of the British batteries. When war once more brewed on the continent, Carleton would be the man who the British government allowed to control defences for Quebec. Other than two tiny islands at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, the French had abandoned the Canadian colonies. But the British and French were no longer the only ones interested in eastern Canada.

For years the population of the 13 British colonies south of the St. Lawrence had separately brooded over taxation and attempts by the British to limit colonization of the North American west. In the spring of 1775, the brooding exploded into violent confrontation near the towns of Concord and Lexington. Those 13 colonies joined the battle to dislodge their British masters.

They had once hoped to be 14.

Quebec was just one of several colonies invited to join the Continental Congress in their fight against British tyranny in 1774, but it was considered the ideal prize. The hated Quebec Act had greatly enlarged Quebec's borders and the colony encased the entire Ohio Valley, among other choice territories. The Americans labelled the act one of the Intolerable Acts and called for its immediate revocation by the British. The territorial slights were bad enough but the Canadians were also denied

habeas corpus

, trial by jury, and representative government under the act. Surely, the Americans reasoned, despite the grants of land, the French Canadians were as outraged by that as they were. It did not occur to the Americans that the French Canadians would not embrace the idea of ridding themselves of the British yoke. The Quebec Act had also guaranteed the French Canadians lan guage and religious freedoms. That alarmed the American leaders, though it must have reassured the Canadians.

The delegates to the Congress drafted a letter and had it translated into French. Two thousand copies were printed and delivered to Canada. In the open letter to the citizens of Quebec, distributed on October 26, 1774, the Americans urged the Canadians to join their cause and become the 14th colony.

Seize the opportunity presented to you by Providence itself. You have been conquered into liberty, if you act as you ought. This work is not of man. You are a small people, compared to those who with open arms invite you into a fellowship. A moment's reflection should convince you which will be most for your interest and happiness, to have all the rest of North-America your unalterable friends, or your inveterate enemies. The injuries of Boston have roused and associated every colony, from Nova-Scotia to Georgia. Your province is the only link wanting, to compleat the bright and strong chain of union. Nature has joined your country to theirs. Do you join your political interests. For their own sakes, they never will desert or betray you. Be assured, that the happiness of a people inevitably depends on their liberty, and their spirit to assert it. The value and extent of the advantages tendered to you are immense.

The colonies' arguments seemed, to them at least, to be perfectly sound and logical. Quebec was joined to the American colonies by geography; it only made sense that the colonies forge political ties as well. To add more punch to their argument they pointed out that Quebec was much smaller and less populous than the rest of the colonies and therefore it would be in Quebeckers best interest to count the Americans as friends rather than enemies. What the Americans did not include in the letter was that they were equally perturbed by the clauses in the Act that ensured the preservation of the French language and gifted numerous rights to French Catholics and perks to the French Catholic clergy. A young Alexander Hamilton, who would later earn fame as one of the founding fathers of the United States, even penned a pamphlet in which he warned that another Inquisition was imminent and American heretics would soon be burning at the stake.

When their first letter was ignored, the Americans sent another on May 29, 1775. That time they entreated the Canadians to join the cause, arguing quite eloquently that they considered the Canadians friends and disliked the idea of being forced to consider them enemies.

In Canada, unsettled by events in the south, the British governor, Sir Guy Carleton, called up the local militia. But having lent two regiments of regulars to the defence of Boston, he had just 800 men at his disposal to protect all of Quebec. He needed the militia but no one wanted to join. The habitants were annoyed that the power to tithe had been restored to the Catholic Church and the Seigneuries, and they were not about to risk their lives to protect them. They were also tired of war and of their farms and fields serving as battlegrounds for foreign troops. Both the British and the Americans had drastically misjudged the Canadians. They were not willing to join the revolution but they were not interested in actively resisting it either. “We have nothing to fear from them while we are in a state of prosperity,” Carleton wrote, “and nothing to hope for when in distress. I speak of the People at large; there are some among them who are guided by sentiments of honour, but the multitude are influenced by fears of gain, or fear of punishment.”

1

While Governor Carleton accepted that the French were allies of convenience only and could not be counted on to defend the country, the Americans refused to accept that the French would not eventually embrace their cause. Popular wisdom within Congress suggested that it was only a matter of time before the oppressed French joined with their American liberators. They just needed to be convinced that the Americans were serious. The way to do that, many suggested, was to invade the country. Once the Americans were at their door, the French would embrace them. Canada, George Washington firmly believed, was ripe for the taking. A young colonel by the name of Benedict Arnold was dispatched to open up the lightly defended route to Lake Champlain. He struck first at Ticonderoga (Fort Carillon), where they met a brief challenge from the single sentry and then roused the commander of the fort from his sleep so he could surrender. Less than 50 men defended Ticonderoga.

Crown Point, the next fort in their path, was even more lightly defended: nine British soldiers guarded the fort. They wisely offered the Americans terms. Buoyed by his quick successes, Arnold ventured over the border to attack Fort St.-Jean. Lacking sufficient troops to hold the fort, he satisfied himself by burning a British ship and helping himself to some of the British stores.

The road to Canada was wide open. Congress was finally ready to act and plans were laid for an invasion. It was to be a two-pronged attack. The first 2,000 man force would be lead by General Philip Schuyler and would use a route that would take the army across Lake Champlain and then up the Richelieu River to invade Montreal and then Quebec City. A second force of just over 1,500 men, commanded by Benedict Arnold, would launch from Boston and head directly to Quebec City.