Candide (7 page)

Authors: Voltaire

“Holy Virgin!” cried she, “what will become of us? A man killed in my apartment! If the police come we are done for.” “Had not Pangloss been hanged,” replied Candide, “he would have given us most excellent advice in this emergency, for he was a profound philosopher. But since he is not here let us consult the old woman.” She was very understanding, and was beginning to give her advice, when another door opened suddenly. It was now one o’clock in the morning, and of course the beginning of Sunday, which, by agreement, belonged to my Lord Inquisitor. Entering, he discovered the whipped Candide, with his drawn sword in his hand, a dead body stretched on the floor, Cunégonde frightened out of her wits, and the old woman giving advice.

At that very moment thought came into Candide’s head. “If this holy man,” thought he, “should call for assistance, I shall most

undoubtedly be condemned to be burned, and Miss Cunégonde may perhaps meet with no better treatment. Besides he was the cause of my being so cruelly whipped; he is my rival; and as I have now begun to dip my hands in blood, I will kill away, for there is no time to hesitate.” This whole train of reasoning was clear and instantaneous ; so that, without giving time to the Inquisitor to recover from his surprise, Candide stabbed him, and laid him by the side of the Jew. ”Here’s another fine piece of work!” cried Cunégonde. ”Now there can be no hope for us; we’ll be excommunicated; our last hour has come! But how could you, who are of so mild a temper, kill a Jew and Inquisitor in two minutes’ time?” “Beautiful miss,” answered Candide, ”when a man is in love, is jealous, and has been whipped by the Inquisition, he is no longer himself.”

undoubtedly be condemned to be burned, and Miss Cunégonde may perhaps meet with no better treatment. Besides he was the cause of my being so cruelly whipped; he is my rival; and as I have now begun to dip my hands in blood, I will kill away, for there is no time to hesitate.” This whole train of reasoning was clear and instantaneous ; so that, without giving time to the Inquisitor to recover from his surprise, Candide stabbed him, and laid him by the side of the Jew. ”Here’s another fine piece of work!” cried Cunégonde. ”Now there can be no hope for us; we’ll be excommunicated; our last hour has come! But how could you, who are of so mild a temper, kill a Jew and Inquisitor in two minutes’ time?” “Beautiful miss,” answered Candide, ”when a man is in love, is jealous, and has been whipped by the Inquisition, he is no longer himself.”

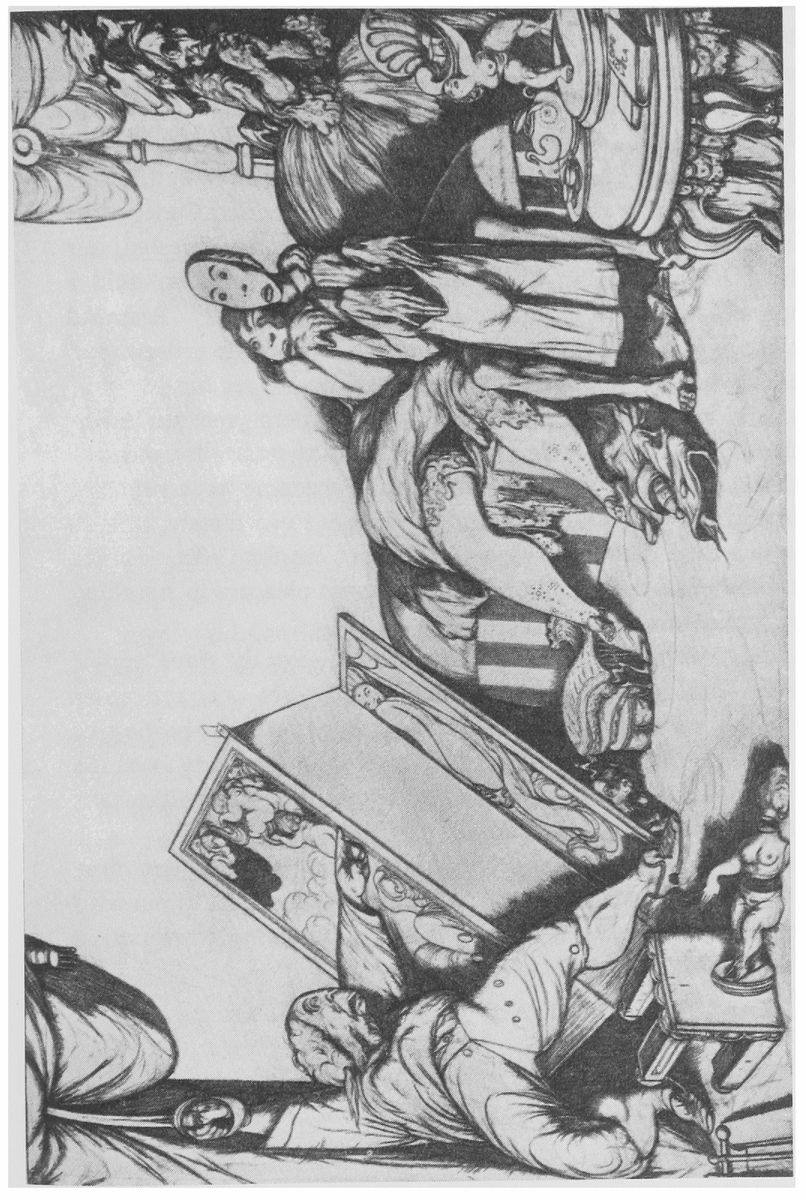

THE RETURN OF DON ISSACHAR

The old woman then put in her word. “There were three Andalusian horses in the stable,” said she, “with their bridles and saddles. Let the brave Candide get them ready; madame has a parcel of gold coins and jewels. Let’s mount the horses immediately, though I have only one buttock to sit on. Let us set out for Cadiz; it is the finest weather in the world, and there is great pleasure in travelling in the cool of the night.”

Candide, without any further hesitation, saddles the three horses; and Miss Cunégonde, the old woman and he set out, and travel thirty miles without a stop. While they were making the best of their way, the Holy Brotherhood

z

entered the house. My Lord the Inquisitor was buried in a magnificent manner; and Master Issachar’s body was thrown upon a dunghill.

z

entered the house. My Lord the Inquisitor was buried in a magnificent manner; and Master Issachar’s body was thrown upon a dunghill.

Candide, Cunégonde, and the old woman had by this time reached the little town of Avecina, in the midst of the mountains of Sierra Morena, and were engaged in the following conversation in an inn where they were staying.

X

In what distress Candide, Cunégonde, and the Old Woman arrived at Cadiz; and of their Embarkation

“W

ho could it be that has robbed me of my gold coins and jewels?” exclaimed Miss Cunégonde, all bathed in tears. “How will we live? what will we do? where will I find Inquisitors and Jews who can give me more?” “Alas!” said the old woman, “I have a shrewd suspicion of a reverend Father Cordelier, who shared the same inn with us last night at Badajoz. God forbid I should condemn any one wrongfully, but he came into our room twice, and he set off in the morning long before us.”

ho could it be that has robbed me of my gold coins and jewels?” exclaimed Miss Cunégonde, all bathed in tears. “How will we live? what will we do? where will I find Inquisitors and Jews who can give me more?” “Alas!” said the old woman, “I have a shrewd suspicion of a reverend Father Cordelier, who shared the same inn with us last night at Badajoz. God forbid I should condemn any one wrongfully, but he came into our room twice, and he set off in the morning long before us.”

“Alas!” said Candide, “Pangloss has often proved to me that the goods of this world are common to all men, and that every one has an equal right to the enjoyment of them;

aa

but according to these principles, the Cordelier should have left us enough to carry us to the end of our journey. Have you nothing at all left, my dear Miss Cunégonde?” “Not a sous,”

ab

replied she. “What can we do, then?” said Candide. “Sell one of the horses,” replied the old woman. “I will ride behind Miss Cunégonde, though I have only one buttock to ride on; and we shall reach Cadiz, never fear.”

aa

but according to these principles, the Cordelier should have left us enough to carry us to the end of our journey. Have you nothing at all left, my dear Miss Cunégonde?” “Not a sous,”

ab

replied she. “What can we do, then?” said Candide. “Sell one of the horses,” replied the old woman. “I will ride behind Miss Cunégonde, though I have only one buttock to ride on; and we shall reach Cadiz, never fear.”

In the same inn there was a Benedictine friar, who bought the horse very cheap. Candide, Cunégonde, and the old woman, after passing through Lucina, Chellas, and Letrixa, arrived finally at Cadiz. A fleet was then getting ready, and troops were assembling, in order to reason with the Jesuit fathers of Paraguay, who were accused of

During their voyage they amused themselves with many profound reasonings on poor Pangloss’s philosophy. “We are now going into another world, and surely it must be there that everything is best; for I must confess that we have had some reason to complain of what passes in ours, in regard to both our physical and moral states. Though I have a sincere love for you,” said Miss Cunégonde, “I still shudder at the thought of what I have seen and experienced.” “All will be well,” replied Candide. “The sea of this new world is already better than our European seas; it is smoother, and the winds blow more regularly.” “God grant it,” said Cunégonde. “But I have met with such terrible treatment in this that I have almost lost all hopes of a better.” “What murmurings and complainings indeed!” cried the old woman. “If you had suffered half what I have done there might be some reason for it.” Miss Cunégonde could scarcely refrain laughing at the good old woman, and thought it droll enough to pretend to a greater share of misfortune than herself. “Alas! you poor old thing,” said she, “unless you have been ravished by two Bulgarians, had received two deep wounds in your body, had seen two of your own castles demolished, had lost two fathers and two mothers, and seen both of them barbarously murdered before your eyes, and to sum up all, had two lovers whipped at an

auto-da-fé

, I cannot see how you could be more unfortunate than I. Add to this, though born a baroness, and bearing seventy-two quarterings, I have been reduced to a cook-wench.” “Miss,” replied the old woman, “you do not know my birth and rank; but if I were to show you everything, you would not talk in this manner, but would suspend your judgment.” This speech inspired a great curiosity in Candide and Cunégonde, and the old woman continued as follows.

auto-da-fé

, I cannot see how you could be more unfortunate than I. Add to this, though born a baroness, and bearing seventy-two quarterings, I have been reduced to a cook-wench.” “Miss,” replied the old woman, “you do not know my birth and rank; but if I were to show you everything, you would not talk in this manner, but would suspend your judgment.” This speech inspired a great curiosity in Candide and Cunégonde, and the old woman continued as follows.

XI

The History of the Old Woman

I

have not always been bleary-eyed; my nose did not always touch my chin; nor was I always a servant. You must know that I am the daughter of Pope Urban X and of the Princess of Palestrina.

15

Until the age of fourteen I was brought up in a castle so splendid that all the castles of your German barons would not have served it as a stable, and one of my robes would have bought half the province of Westphalia. I grew up, and improved in beauty, wit, and every graceful accomplishment; and in the midst of pleasures, dignities and the highest expectations. I was already inspiring young men to love. My breast began to take its right form: and such a breast—white, firm, and formed like that of Venus of Medicis. My eyebrows were as black as jet; and as for my eyes, they darted flames, and eclipsed the lustre of the stars, as I was told by the poets of our part of the world. My maids, when they dressed and undressed me, used to fall into an ecstasy whether viewing me from in front or behind; and all the men longed to be in their places.

have not always been bleary-eyed; my nose did not always touch my chin; nor was I always a servant. You must know that I am the daughter of Pope Urban X and of the Princess of Palestrina.

15

Until the age of fourteen I was brought up in a castle so splendid that all the castles of your German barons would not have served it as a stable, and one of my robes would have bought half the province of Westphalia. I grew up, and improved in beauty, wit, and every graceful accomplishment; and in the midst of pleasures, dignities and the highest expectations. I was already inspiring young men to love. My breast began to take its right form: and such a breast—white, firm, and formed like that of Venus of Medicis. My eyebrows were as black as jet; and as for my eyes, they darted flames, and eclipsed the lustre of the stars, as I was told by the poets of our part of the world. My maids, when they dressed and undressed me, used to fall into an ecstasy whether viewing me from in front or behind; and all the men longed to be in their places.

I was engaged to a sovereign prince of Massa Carara. Such a prince! as handsome as myself, sweet-tempered, agreeable, witty, and in love with me madly. I loved him too, as one loves for the first time, with devotion approaching idolatry. The wedding preparations were made with surprising splendour and magnificence; there were feasts, carousals, and burlettas; all Italy composed sonnets in my praise, though not one of them was tolerable. I was on the point of reaching the summit of bliss, when an old marquise, who had been mistress to the prince my husband, invited him to drink a cup of chocolate. In less than two hours after he returned from the visit, he died of the most terrible convulsions. But this is a mere trifle. My mother, distracted to the highest degree, and yet less afflicted than I, determined to escape for some time from the funereal

atmosphere. As she had a very fine estate in the neighbourhood of Gaieta,

atmosphere. As she had a very fine estate in the neighbourhood of Gaieta,

ac

we embarked on board a galley, which was gilded like the high altar of St Peter’s at Rome. At sea, we were raided by a pirate ship from Salé.

ad

Our men defended themselves like true pope’s soldiers ; they flung themselves upon their knees, laid down their weapons, and begged the corsair to give them absolution

in articulo mortis

.

ae

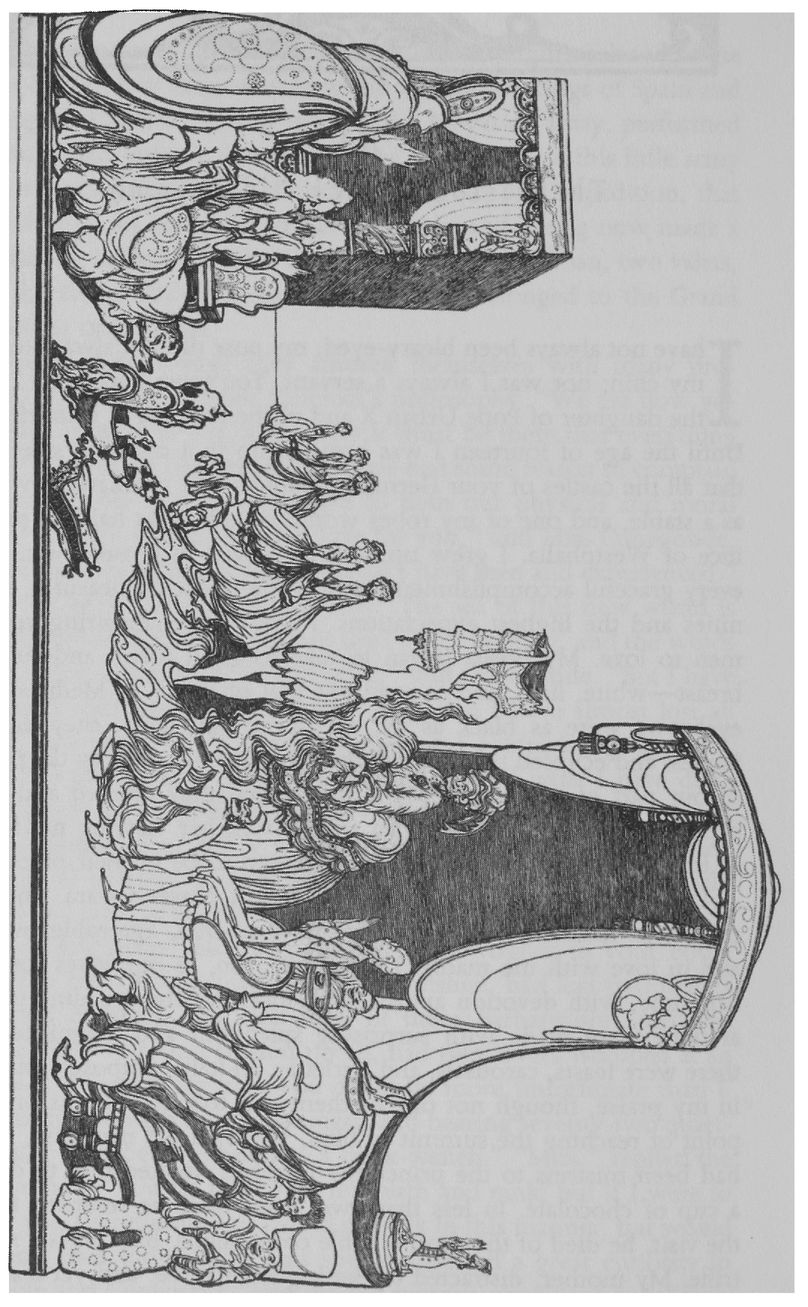

THE TOILET OF THE POPE’S DAUGHTER

ac

we embarked on board a galley, which was gilded like the high altar of St Peter’s at Rome. At sea, we were raided by a pirate ship from Salé.

ad

Our men defended themselves like true pope’s soldiers ; they flung themselves upon their knees, laid down their weapons, and begged the corsair to give them absolution

in articulo mortis

.

ae

The Moors presently stripped us as naked as monkeys. My mother, my maids of honour, and myself were all treated in the same manner. It is amazing how quick these gentry are at undressing people. But what surprised me most was, that they thrust their fingers into every part of our bodies that their fingers could in any way reach. I thought it a very strange kind of ceremony; for that is how we are generally apt to judge of things when we have not seen the world. I learnt afterwards that it was to discover if we had no diamonds concealed. This practice has been long-standing among those civilised nations that scour the seas. I was informed that the religious Knights of Malta never fail to make this search whenever any Moors of either sex fall into their hands. It is one of those international laws from which they never deviate.

I need not tell you how great a hardship it was for a young princess and her mother to be made slaves and carried to Morocco. You may easily imagine that we must have suffered on board the pirate ship. My mother was still extremely handsome, our maids of honour, and even our common waiting-women had more charms than were to be found in all Africa. As to myself, I was enchanting; I was beauty itself, and then I had my innocence. But alas! I did not retain it long; this precious flower, which was reserved for the lovely prince of Massa Carara, was plucked by the captain of the Moorish vessel, who was a hideous negro, and thought he did me infinite honour. Indeed, both the Princess of Palestrina and myself must have been very strong indeed to undergo all the hardships and violences we suffered till our arrival at Morocco. But I will not detain you any longer with such common things; they are hardly worth mentioning.

Upon our arrival at Morocco we found that kingdom bathed in blood. Fifty sons of the Emperor Muley Ishmael

af

were each at the head of a party. This produced fifty civil wars of blacks against blacks, of browns against browns, and of mulattoes against mulattoes. In short, the whole empire was one continued scene of car-cases.

af

were each at the head of a party. This produced fifty civil wars of blacks against blacks, of browns against browns, and of mulattoes against mulattoes. In short, the whole empire was one continued scene of car-cases.

No sooner were we landed than a party of blacks, of a faction hostile to my captain, came to rob him of his booty. After the money and jewels we were the most valuable things he had. I was witness on this occasion to such a battle as you never see in your cold European climates. The northern nations do not have the hot blood, nor that raging lust for women that is so common in Africa. The natives of Europe seem to have their veins filled with milk only; but fire and vitrol circulate in those of the inhabitants of Mount Atlas and the neighbouring provinces. They fought with the fury of the lions, tigers and serpents of their country, to decide who should have us. A Moor seized my mother by the right arm, while my captain’s lieutenant held her by the left; another Moor laid hold of her by the right leg, and one of our corsairs held her by the other. In this manner were almost every one of our women dragged between four soldiers. My captain kept me concealed behind him, and with his scymetar cut down every one who opposed him; at length I saw all our Italian women and my mother mangled and torn to pieces by the monsters who were fighting over them. The captives, my companions, the Moors who took us, the soldiers, the sailors, the blacks, the whites, the mulattoes, and lastly, my captain himself, were all slain, and I remained alone, half-dead upon a heap of dead bodies. Similar barbarous scenes were occurring every day over the whole country, which is an extent of three hundred leagues, and yet they never missed the five stated times of prayer decreed by their prophet Mahomet.

I untangled myself with great difficulty from this vast heap of slaughtered bodies, and crawled to a large orange tree that stood on the bank of a neighbouring rivulet, where I fell down exhausted with fatigue, and overwhelmed with horror, despair and hunger. My senses being overpowered, I fell asleep, or rather seemed to be in a trance. Thus I lay in a state of weakness and insensibility, between life and death, when I felt myself touched by something that moved up and down upon my body. This brought me to myself; I opened my eyes, and saw an attractive, fair-faced man, who sighed, and muttered these words between his teeth: “O che sciagura d’essere senza coglioni!”

ag

ag

Other books

Put a Lid on It by Donald E. Westlake

Chains and Memory by Marie Brennan

After the Death of Anna Gonzales (9781466859524) by Fields, Terri

Rebound by Cher Carson

Roses of Winter by Morrison, Murdo

Three Down the Aisle by Sherryl Woods

Gone and Done It by Maggie Toussaint

She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth by Castor, Helen

Belonging to Bandera by Tina Leonard

Last of the Red-Hot Cowboys by Tina Leonard