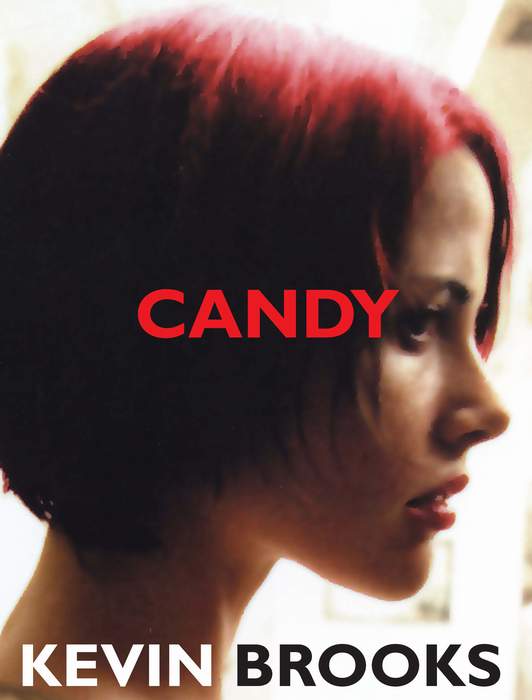

Candy

Kevin Brooks

SCHOLASTIC INC.

New York Toronto London Auckland Sydney

Mexico City New Delhi Hong Kong Buenos Aires

I

t’s hard to imagine life before Candy. Sometimes I sit here for hours, staring into the past, trying to remember what it was like, but I never seem to get very far. I just can’t see myself without her. About the best I can manage is the last half hour before we met, the last few moments of my pre-Candy existence, when I was still just a boy…just a boy on a train, a boy with a lump, a boy in a starry black hat.

I was innocent then.

Just a boy.

On a train.

With a lump.

And a hat.

That was all the world I needed to know.

It was Thursday, February 6, about five o’clock in the afternoon, and the London-bound train was almost empty. The trains passing by on the opposite track were packed to the roof with steamed-up commuters heading

back home after a hard day’s work, but the only other passengers traveling with me were a couple of shift workers, a drunk guy in a suit, and a gaggle of good-time girls setting off early for a night on the town. I couldn’t actually

see

the girls—they were sitting somewhere behind me—but I could hear them giggling and laughing and screeching at one another, letting everyone know how much they were enjoying themselves. It was hard

not

to listen to them, harder still when they started their full-volume whispering—

You shoulda seen it, Jen—like THIS

…

No!

I nearly DIED, girl…

Heeeeee!!

When the girls had got on the train—at the stop after mine—I’d slouched down low in my seat and turned my head to the window. I was pretty sure they couldn’t see me—they were right at the back of the carriage and I was somewhere in the middle—but I didn’t want to take any chances. You know how it is—there’s six of them and only one of you…and they’re all dolled up, flashing themselves about, and they’ve had a few drinks…and you’re wearing a brand-new hat, which you’re not quite sure about, so you’re already feeling a bit self-conscious…and you know what’ll happen if they see you…they’ll

say

something, or

do

something—just for a laugh—and you’ll start getting embarrassed, and that’ll encourage them to say something else, and then you’ll get even

more

embarrassed…

Well, anyway, that’s what I’d done when the girls had got on the train. I’d slumped down low in my seat and kept out of sight, resting my head against the window and watching the world pass by.

And I was still watching it now.

There wasn’t much to see in the graying light—trackside tower block, packing factories, parks, city lights winking in the distance—and after a while I found myself staring at nothing and listening to the rattle and hum of the carriage, the rhythm of the tracks—

ducka-dah-dum, DACKa-dah-dum, ducka-dah-dum, DACKa-dah-dum…

making up songs in my head.

I was always doing that back then—making up songs, playing tunes in my head, dreaming the music…

It used to keep me going.

It used to mean something.

One day, hopefully, it’ll mean something again.

As the train approached Liverpool Street station, I kept on staring through the window and listening to the sounds of the carriage. The announcer was reminding us not to leave our personal belongings on the train, the girls were laughing at his Asian accent, and the other passengers were standing up, getting their bags, getting ready to leave. We were trundling along through an old brick tunnel lined with wires and cables and trackside waste. There were dark little caves in the tunnel wall, small shadowed arches, like tunnels within tunnels. In some of these caves I could see statues—strange crumbling figures entombed in brick, their weatherworn faces fringed with purple weeds—and as the train rattled past, I wondered idly what they were—ancient decorations? relics? railway gods?—and what they were doing there. I mean, why put statues in a

tunnel?

I was still thinking about it when the train slowed to a crawl, the darkness lifted, and we hissed to a halt in the sterile light of the station platform.

Psshhhh…

Dunk.

Aaaahhh…

I let the other passengers off first. As the girls pushed and shoved and cackled their way through the door and headed off along the platform, their high-heeled shrieks echoing coldly around the station, I sneaked a quick look at them through the window. I was surprised to see how young they were. From the way they’d been talking I’d imagined them to be in their late teens or early twenties, but most of them were only about fifteen or sixteen—and that confused me for a minute. They were about the same age as me…but somehow they didn’t

feel

the same age, and I wasn’t sure how or why. I didn’t feel older than them, but I didn’t feel younger, either.

I just felt different.

For a moment or two, I wondered where they were going, and what they were going to do, and what they’d find at the end of their night—love, sex, happiness, oblivion, a drunken slap in the face?

Then I picked up my plastic bag, adjusted my hat, and got off the train.

The concourse was crowded with hordes of commuters, everyone rushing and racing and fighting for trains. There were thousands of them, pouring in from the streets and the tube station in a never-ending tide of dark suits and briefcases and hurry-up faces, like some kind of manic migration. The noise was incredible—a swirling cacophony of shuffling feet and crowded voices, tannoy announcements, railway shouts, hissing trains, squealing wheels, the metallic clacking of the indicator board, all of it

merging together to form a vast blind noise that whirled and swarmed and rose up into the glass-domed roof like the sound of a million birds.

I moved across the concourse as quickly as I could—dodging from side to side, struggling against the tide—and made my way down to the tube station. More struggling. More harried faces. More cacophony. I kept going—through the ticket barriers, along the corridor, over the bridge, down the steps—and then, with a last-second sprint and a heart-stopping leap, I was just another face on a Circle Line train, heading back into the darkness.

Breathing hard, I leaned against the door and wiped the cold sweat from my face and looked up at the tube map on the wall: Liverpool Street, Moorgate, Barbican, Farringdon, King’s Cross.

Four stops.

Not long to go, now.

Not long for the boy.

Whenever I go to London, I always feel embarrassed if I have to look at an A-Z map. I know it’s stupid. I know there’s no

reason

to feel embarrassed. It’s only a

map,

for God’s sake. If you don’t know where you’re going, you take a map, don’t you? What’s wrong with that? It’s a perfectly sensible thing to do.

I

know

that.

It’s just…I don’t know. It’s just a matter of

cool,

I suppose. London is cool. Londoners are cool. You don’t want them thinking you’re some kind of village idiot, do you?

I mean, come

on…

Yeah, I know—it’s pathetic. But pathetic’s not so bad, is it? I mean, there are worse things in the world than being pathetic.

Anyway, that’s why I was carrying my A-Z wrapped up in a plastic bag and hidden away in my pocket, and that’s why, when I came out of King’s Cross tube station, out into the cold city night, I didn’t know where I was. I knew where I was

supposed

to be and I knew where I was supposed to be going, but I hadn’t come out where I’d expected to come out, and I’d lost all sense of direction. The place I was going to was on Pentonville Road, and I knew where that was because I’d looked it up earlier in the A-Z. But I only knew where it was in relation to Euston Road, which runs alongside the front of the station, and I hadn’t come out at the front of the station; I’d come out somewhere else, a side exit or something. And all I could see, everywhere I looked, was chaos: cars, buses, taxis, speeding bikes, flashing lights, roadworks, cranes, building sites, pedestrian crossings, signposts, junctions, more commuters, street people, mad people, blank-faced hippies with long dirty hair and scabs on their faces…

None of

that

was in the A-Z.

And I didn’t want to get it out of my pocket, anyway. There were far too many people around, and I was feeling pretty uncool as it was—standing there like a slack-jawed yokel, blinking at the lights and the noise. I wouldn’t have looked more out of place if I’d been dressed in a dirty old T-shirt and dungarees, with a blade of dry grass sticking out of my mouth…and a little white pig at my feet…a little white piggy on a tattered rope leash…

Shaking the image from my head, I stepped back and leaned against a wall for a minute to get my bearings. Taking my time, breathing in the rubbery stink of buses, the choke of exhaust fumes…looking around, thinking about things, looking around some more…looking looking looking…thinking thinking thinking…until, finally, it dawned on me what I had to do. It was so simple I felt like an idiot for not thinking of it before. To find out where I was, all I had to do was head for the main station building—which I could see looming up in the black sky behind me—and start from there.

So that’s what I did.

Up the street, around a corner, and there I was—on a broad paved area, dotted with telephone booths and newspaper stands, right outside the station. Right next to Euston Road.

Piece of cake.

Now all I had to do was follow Euston Road…

But…which way?

This way?

Or that way?

Left or right?

I closed my eyes, trying to picture the A-Z. I could see it, I could see all the roads, but the map was upside down in my head. The page was the wrong way around. The station was on the wrong side of the road.

All right,

I said to myself,

if the road’s upside down on the map, all you have to do is go the other way. If you’re on

this

side of the road, which is the

other

side on the map, then instead of going right, you have to go left.

I started moving off to the left, then paused, remembering

something—the map was

supposed

to be upside down. When I’d looked at the A-Z before leaving home, I’d turned it upside down so the page

was

the right way around. The map in my head was right all along. I didn’t want to go right; I wanted to go left.

So I turned around, bumping into a crazy old woman pushing a shopping cart full of rags—“Yageddabadda geddaahh!”—and moved off back the way I’d come.

But I hadn’t taken more than half a dozen steps when I stopped again, reconsidering the map. Had I

really

turned it around? Maybe not. Maybe I was right in the first place?

I half-turned, thought about it again, turned back, and was just about to get going for the final time when a voice called out from behind me.

“You want to make your mind up.”

It was a girl’s voice—sweet and clear, like a shining jewel in the gutter. It wasn’t particularly loud—she wasn’t shouting or yelling—but somehow the sound of it managed to cut through the chaos and pinpoint my mind like the diamond-tipped blade of a knife. I turned around, taking in a sea of blurred faces, and there she was—standing in the doorway of Boots, leaning against the wall, smiling at me. It was the kind of smile that rips a hole in your heart—lips, teeth, sparkling eyes…

God, she could smile.

I didn’t do anything. I

couldn’t

do anything. All I could do was stand there looking at her. Looking at everything. Her face, her lips, her cheeks, her dark almond eyes. Her neck, her legs, the shape of her body. Her pale white skin. The gleam of her chestnut hair, tied in a ponytail…

God…her skin.

She was wearing a tight little skirt and a loose crop top, revealing a flash of bare skin that turned me to stone. Then there was the lipstick, the mascara, the bracelets on her wrist, the leather bands on her upper arm, the silver cross around her neck, the black leather boots…

I didn’t know what to do.

What was I supposed to do?

I tried to smile, but my mouth was bone-dry, my lips stuck together at the corners. I probably looked like a mental patient. I wiped my mouth and looked at her again, trying to think of something to say, but my head was empty. She cocked her head and glanced to one side, then smiled and looked back at me again.

“Nice hat,” she said.

Without thinking, I put my hand to my head and touched my hat. It was a new one—a black beanie with a ring of gold stars around the edge. I really liked it. The thing about hats, though—sometimes they can give out the wrong signals. People think you’re trying to be special—wearing a hat, showing off, trying to be something you’re not. I don’t know…maybe it’s just me; maybe I’m paranoid or something. I mean, I know it doesn’t matter—it’s only a

hat,

for God’s sake. And, besides, who

cares

what other people think?

Not me, obviously.

Anyway, I didn’t put my hand to my head because I thought the girl was being malicious or anything; I did it out of habit. I knew she wasn’t being malicious. It was just a compliment, that’s all.

She liked my hat.

I

knew

that.

So…what did I say?

“Uh…yeah.”

That’s what I said.

Uh…yeah.

Stunning, eh?

Highly impressive.

Cool as hell.

And now the girl was going. She’d folded up a small plastic bag in her hand, adjusted her handbag, pushed herself away from the wall, and now she was walking off—just like that. She was going. A sway of her hips, a quick smile over her shoulder…then she turned her head and melted back into the chaos.

No,

I thought.

Hold on…

No…

But I was too late.

She’d gone.

Shit.

I stood there for a while, staring after her, replaying the scene in my head.

It happened,

I told myself.

You didn’t imagine it. It happened. She was there…and now she’s gone. She was there…

And now she’s gone.

So forget it.

It was nothing—OK? She probably wasn’t even talking to you, anyway. She was probably talking to a friend of hers, someone standing behind you…yeah, that’s probably it.