Cantona (46 page)

Authors: Philippe Auclair

‘And Éric?’ I heard myself say. ‘Did you see him there?’

‘Yes, once. He was different. People were doing the most outrageous things on the first floor, but he couldn’t have cared less. He remained himself. Imperious, you know, the chest like that, upright, very dignified. What he did he did with class . . . or, rather, he acted as if he wanted people to say, “Ha, he’s got class!” – there’s a difference, you see.’

British tabloids would have paid a small fortune to find an eyewitness of the goings-on at Chez Adam. In fact, one of them got wind of the rumours at the time of Éric’s fictitious dalliance with Lee Chapman’s wife, Leslie Ash, and approached a journalist fiend of mine, who turned down their offer of £5,000 for a detailed account of Cantona’s visits to the club. That Éric had – just like his father, Le Blond’ – an eye for the ladies was hardly a secret. He was being himself, sticking to his oft-declared ‘principle’ of going wherever his impulses told him he should go, whatever the cost may be to himself and to others. In the video

Éric the King,

which Manchester United released in November 1993, he said: ‘I have a kind of fire inside me, which demands to be let out, and releasing it is what fuels my success. I couldn’t possibly have that fire without accepting that sometimes it wants to come out to do harm. It is harmful. I do myself harm. I am aware of doing myself harm and doing harm to others.’ These quotes resurfaced later, in the wake of his moment of madness at Selhurst Park. But Éric was not just talking about football. It was the confession of an egotist

malgré lui,

who had found that the only way he could live with and, yes, control his raging desires was to give vent to them. That it led him to feel remorse is beyond doubt. Éric was a genuinely generous person, who derived great joy from pleasing those he loved, the ‘good man’ that so many of those who knew him best talked to me about. His spontaneity absolved him of mere callousness – until he used it as justification for the unjustifiable. Here, as in so many aspects of his personality, the man who saw the world in black and white became a blur of grey.

And that is why what Cantona did or did not do at Chez Adam does not matter. What is far more significant is that it gave me more proof that, contrary to what Éric has claimed so often, he couldn’t live without the football environment he despised or the players he had nothing good to say about. He might not have liked it, but he was one of them. Many teammates – Ryan Giggs, Roy Keane, Gary McAllister, to name but three – have expressed surprise at the idea that the ‘true’ Cantona was some kind of desperado who only felt at ease away from the crowd, with his dogs, his easel or a shotgun slung across his shoulders. He had been the ringleader of Auxerre’s pranksters. He organized hunting parties with OM players. He treated his Montpellier teammates to a birthday dinner, and celebrated their French Cup triumph late into the night. He climbed down a gutter to spend a night on the town in Dublin with a Leeds United teammate. He joined Manchester United’s drinking club (on his terms: champagne, rather than beer). He behaved like a

seigneur

at Chez Adam. Solitary and gregarious, forgiving and implacable, by turns loyal and cruel to his friends, he had barely changed from the little boy who watched Ajax, perched on Albert’s shoulders. He still longed for reassurance and warmth, and craved the togetherness that football, despite its faults and its hypocrisies, had provided him with since he could walk. When he rejected it publicly, he was also admitting a double failure. He couldn’t find a balance outside of the game. And he couldn’t bring himself to admit it. He would have to kill the footballer to become a man, a prospect he had every right to be terrified of. What and who could that man be?

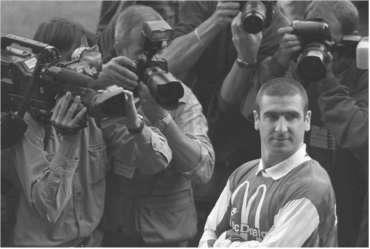

The other Cantona: a dream for advertisers.

THE CONSECRATION: 1994

‘Doubt? Me? Never. But I’m different. I’m a bit of a dreamer. I feel I can do everything. When I see a bicycle, I’m sure I can beat the world record and win the Tour de France.’

Éric Cantona celebrated the first anniversary of his arrival in English football in the most appropriate manner: with another goal, his eighth in the league that season. It was at Coventry on 27 November, a game in which United’s dominance was such that they only played for fifteen minutes before shutting up shop and driving away with as emphatic a 1–0 victory as could be wished for. Phil Neal, who had just been named head coach of the defeated side, had an unusual compliment for Éric, whom he called ‘one intelligent beast of a footballer’ – an inspired oxymoron that captured the feeling of confidence oozing from his performances. A week earlier, Wimbledon had been the victims of that intelligence when he had supplied Andreï Kanchelskis and Mark Hughes with goalscoring opportunities they couldn’t miss. The Dons lost 3–1, giving United their eighth consecutive win in the league and extending their lead to 11 points. With Coventry beaten, the gap grew to 14.

‘[Éric] has completely confounded the critics who said he was trouble,’ Ferguson said. ‘[He is] the fulcrum of our side.’ The manifest superiority of his team didn’t reflect well on the standard of the recently formed Premier League, but said a great deal about Cantona’s capacity to spring back from France’s heartbreaking elimination from the World Cup. On the last day of November, Everton were brushed aside 2–0 at home in the fourth round of the League Cup, despite United having three goals chalked off in the last 15 minutes of the game. And when those around him were having an off-day, Éric shook them from their apathy: two more assists, the first for Giggs, the second for McClair, the culmination of a stupendous nine-pass move, ensured United salvaged a 2–2 draw against a combative Norwich at Old Trafford in early December. The only worrying sign for Ferguson was a resurgence of Éric’s indiscipline, first noticed when he was lucky to escape dismissal after kicking at Norwich defender Ian Culverhouse, who had been harrying him by fair means and foul for most of the game.

Fans were beginning to forget when United had last lost in England. Sheffield United – destroyed 3–0 at Bramall Lane, Cantona making the most of a ‘telepathic’ pass from Ryan Giggs to conclude the scoring. A 1–1 draw at Newcastle. A 3–1 demolition of Aston Villa, the previous season’s most resilient challengers, which prompted Ron Atkinson to say: ‘The only way anyone will catch them is if the rest get six points for a win and they don’t get any.’ By 19 December United had amassed 52 points, a ‘ridiculous’ total with only half of their games played. A jubilant Cantona could claim he was now in ‘the best team [he’d] ever played for’. Atkinson had given Earl Barrett the task of following the Frenchman’s every move, the very first time an English manager had tried to negate Cantona’s influence by placing a shadow in his trail. The ploy failed, dismally. Éric scored twice. ‘He was unbelievable,’ Ferguson said. ‘Ron Atkinson has always played 4-4-2, but he changed all his principles to man-mark Éric Cantona, and you can’t get a greater accolade than that.’

There could’ve been one, of course. Late in December, it was announced that

France Football’s Ballon d’Or

had been awarded to Roberto Baggio, winner of the UEFA Cup and scorer of 21 goals in 27 games for Juventus in Serie A. The European jurors had placed Éric third in their votes, the only time in his career that he ended on the podium of the most prestigious of football’s individual awards. Cantona’s pride at having been considered one of the worthiest pretenders to the trophy was obvious, but his response was remarkable for its genuine humility. He extolled the beauty of Dennis Bergkamp’s play (the Dutchman, who had just left Ajax for Internazionale, had narrowly lost to the Italian playmaker), focusing on the collective ethos of the

Oranje

‘who work like crazy’. ‘The team makes the individual,’ he said. ‘It’s an exchange. You need a lot of personality to accept putting yourself at the service of someone else. The creator doesn’t exist without this tacit agreement.’ If the

Ballon d’Or

jury had failed (‘gravely’, according to Éric) in one regard, it was in ignoring the claim of players in the mould of Paul Ince. ‘Guys like him make people like me shine,’ he said.

Shine he did. It wasn’t a competition any more, but a procession, a litany. A 1–1 draw against Blackburn on Boxing Day brought United’s unbeaten run to 20 games, then 21 with a 5–2 atomization of Oldham three days later. In the 1993 calendar year, United had scored 102 points, 26 more than the second best, Blackburn, scoring 2.13 goals per game in the 1993–94 season. Statistics like these augured a long supremacy, the like of which English football hadn’t seen since Liverpool collected seven titles between 1977 and 1984, and it was confidently predicted that 1994 would see a confirmation of that trend. That wasn’t quite the case, however.

A drop in form had to check United’s progress at some stage, but it’s fair to say that no one saw it coming. The 0–0 they brought back from Eiland Road on New Year’s Day didn’t constitute much of a surprise. Five of the six ‘Roses’ derbies which had taken place since Leeds regained elite status in 1990 had ended in draws and, after dicing with relegation in the months following Éric’s departure, Howard Wilkinson’s side had rediscovered some of its former grit and efficiency, and spent most of the autumn solidly installed in the pack chasing United. Cantona was given the reception he could expect from the crowd, as well as a robust welcome by Chris Fairclough, who frustrated him so much that Éric was very lucky not to be dismissed for a stamp on the defender. Another bad foul forced referee David Elleray to caution him, but Cantona was by then playing with a persistent, silent fury. The official chose to give him a lengthy lecture when he could easily have produced another yellow card later in that game. Not all his colleagues would be prepared to show the same leniency in the coming months. Éric’s bad-tempered display gave Wilkinson a chance to have a dig at his former player: ‘He is the same player on a different stage, in different circumstances,’ he said. ‘When he was on my stage, we were losing football matches. Those were not performances conducive to the way he played, so I left him out, he didn’t like it, and he asked to go.’ In other words, put Cantona in a winning team, and he’ll look like a world-beater; but don’t count on him when the wind is not blowing fair any more.

Three days later, it was a gale that swept through Anfield, on a raw night that signalled that some complacency was creeping into the leaders’ performances. United contrived to lose a three-goal lead at Liverpool. But as every single one of their rivals took it in turns to lose when they looked poised to challenge, Alex Ferguson could console himself with a look at the table: his team still led by 13 points. In truth, the fluency of the preceding months seemed to have deserted United. They were scrapping for results: 1–0 against Sheffield United in the Cup, Éric missing an open goal; then 2–2 against first division Portsmouth in the League Cup, their fourth draw in five games.

36

Even if the champions were scarcely in danger of suffering the kind of physical and mental decline that wrecked their 1991–92 season, the fact remained that their standards had been slipping for several weeks. They needed a performance that would reassert the emergence of a new order in English football. Éric, who had just recovered from a heavy cold, took it on himself to make sure it would be in their very next game.

The majesty of Cantona’s play in United’s 1–0 victory over Spurs on 15 January was such that the White Hart Lane crowd joined the travelling supporters in applauding him off the field.

The Times

saluted Éric’s ‘flair, fitness and enthusiasm bordering on fanaticism’ and already installed him as favourite for the title of ‘Footballer of the Year’. United now needed just 23 points from 16 games to be champions again, and, whatever Howard Wilkinson might have had to say, it was primarily thanks to the prodigious imagination, coolness in front of goal and stamina of the Leeds reject. Ferguson’s gamble had paid off, and handsomely.

On 22 January a lone piper playing ‘A Scottish Soldier’ slowly led the footballers of Manchester United and Everton on to the field of play. Flags were flying at half-mast, and one seat was empty in the directors’ box – that of Sir Matt Busby, whose long struggle with cancer had ended two days previously. The architect of United’s extraordinary ascent in the 1950s and 1960s would always end his pre-match team talks with one of two valedictions – ‘And now, enjoy yourselves’, or ‘Have fun!’ That day, Cantona played as if it had been Busby, not Ferguson, who had sent him on. At one point, he cushioned Ryan Giggs’s dipping cross on his chest and, in one movement, swivelled to send a half-volley crashing on to the post. The opposition’s manager, Mike Walker, was mesmerized by United’s performance. ‘There is an aura about [them],’ he said. ‘They are streets ahead of the rest and their players know it. There is a swaggering arrogance about them, and this is not a criticism. [ . . .] You have no idea where their next move is coming from. You plug one hole and another one opens up. You fill that, another player comes at you.’ Walker had no hesitation in singling out Cantona as the choreographer of United’s ballet: ‘He brought it all together last season. His presence has allowed the others to play better. You can see that.’ So could Portsmouth, beaten 1–0 in the replay of their League Cup quarter-final, Éric’s glancing header setting up Brian McClair for the winner. So could Norwich, dumped out of the FA Cup on 30 January, Keane and Cantona providing the goals in a 2–0 victory – not that the goals provided the talking point in the evening’s highlights programme on television.