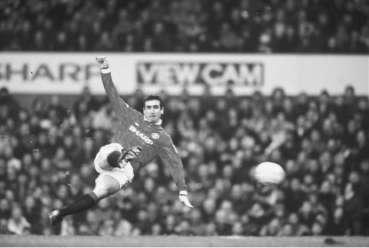

Cantona (58 page)

Authors: Philippe Auclair

‘Months passed by. We didn’t talk about it. Then [French television network] TF1 sends me to Manchester United–Dortmund, and asked me to organize an interview with Cantona, who hadn’t talked to French television for a year. Éric said: “Guy Roux – yes. With a cameraman and no one else.” We locked ourselves in and did the interview. Then I told him the story . . . and he says: “Of course, that’s it! I hadn’t understood at the time! My lawyers were rubbish!”

‘Was it so? No one will ever know, until the archives are open to the public.’

THE AFTERMATH AND THE RETURN OF THE KING: APRIL–DECEMBER 1995

‘My lawyer and the officials wanted me to speak. So I just said that. It was nothing, it did not mean anything. I could have said, “The curtains are pink but I love them.”’

Soberly dressed in white shirt, black V-necked jumper, grey flannel jacket and matching two-tone silk tie, Éric Cantona sat down to confront the throng of journalists who had assembled at the courthouse. The incessant clicking of the cameras and the fizz of the flashing lights made a noise like thousands of raindrops clattering on a tin roof Éric delivered a single sentence of twenty words in precisely fourteen seconds, fated to become one of the most celebrated quotes in the history of football.

When the seagulls [

a sip of water

] follow a trawler [

the ‘a’ almost inaudible, leaning back, smiling, pausing again

], it’s because they think [

another pause

] sardines [

and another

] will be thrown into the [

slight hesitation

] sea [

a smile and a quick nod

]. Thank you, very much.

Incredulous guffaws accompanied Cantona as he made his way out of the heaving room. The bemusement of the journalists was understandable: they had been expecting a press conference, possibly more words of repentance, instead of which ‘Le nutter’ had just cocked a snook at his tormentors, pirouetted on his heels and left them with gaping mouths. Much was made of the ‘sybilline’ nature of the pronouncement, when, in truth, everyone understood Cantona’s meaning; but no one could bring themselves to accept that he had had the cheek to steal the show in such a light-hearted – and memorable – manner. The ‘seagulls’ (the press, of course) could have been other animals – vultures, for example. Incredibly, the carcass had spoken. It hadn’t been thrown overboard after all, and wouldn’t give the scavengers as much as a bone to chew on. The disingenuousness of some commentators, who claimed these words were those of a certifiable lunatic, did not fool the general public. All of England – then, within hours, most of the watching world – fell about laughing. Éric’s teammates joined in the merriment. Steve Bruce and Gary Pallister would rib Cantona for months to come in the dressing-room – sardines-this and sardines-that – to Éric’s undisguised delight. He had never told a better joke. He had diverted the media’s attention from the consequences of his faux pas, and given them another basis on which to build the legend ever higher. He would never speak to a journalist again while at United, unless he had been dispatched by his club to provide material for an official book or video, one of several steps he took to wipe the slate clean and draw a new picture of himself.

48

It took time to take shape, naturally, and it wasn’t until much later in the season to come that it became clear that Cantona, against all odds and all predictions, had succeeded in doing so.

Films of Cantona shot during his ban show him on his own, running around a training pitch or lifting weights in United’s gymnasium. In fact, he trained with his teammates throughout his enforced absence, apparently taking ‘it all in his stride’, according to Ryan Giggs. Most observers were convinced that it would only be a matter of weeks before a foreign club, probably Italian, and more precisely Inter Milan, would rescue Cantona from his English predicament, but Alex Ferguson thought otherwise. ‘We know it will be difficult for [him] to return to normal football in this country,’ he said as early as 4 April, ‘but we think it is possible. I’ve said all along we want him to stay, and together we can work it out.’

The

Daily Mirror

disagreed. On 12 April, on the day a Crystal Palace fan called Paul Nixon was killed in a scuffle before their FA Cup semi-final replay against United (in which Roy Keane was sent off and ‘appalling’ Cantona songs rang around Selhurst Park), the tabloid announced that Éric’s transfer to Internazionale was now a certainty. Cantona had instructed his adviser Jean-Jacques Bertrand to open negotiations. The Italians would increase the player’s salary five-fold, to £25,000 a week, while offering his present club £4.5m. Bertrand immediately denied that a deal had been struck, but admitted that there had been some contact, which was the truth; as we know, Moratti had approached the United board long before Éric’s troubles, and was unlikely to let go now that his target seemed to have forsaken a future in English football. In Manchester, meanwhile, supporters could hardly be reassured by club statements such as: ‘We’ve always said that we wanted Éric to stay, but we want players who want to stay with us’ – which was as good as saying that the door leading Cantona out of Old Trafford had been left ajar, if not quite opened for him. Martin Edwards professed more optimism himself – United were conducting their own negotiations with Bertrand – but only up to a point. ‘A lot depends on what Éric wants to do,’ he said. ‘If he wants to play for United he is certainly going to receive a very good offer from us, but if he feels he has had enough of England or that he is in an impossible position because of the problems he has had, then that is a different matter.’

Doubts would linger for months to come. One close confidant of Cantona’s told me that the player had indeed been ‘that close’ to moving to Italy at the time. The urge to leave England and the lure of phenomenal wages were not the only factors preying on Éric’s mind. He felt that Manchester United should have made far more effort to bring in the top-class players required to achieve the club’s oft-stated ambition to rejoin Europe’s footballing elite. The names of Gabriel Batistuta, Marcelo Salas and even Zinédine Zidane had been mentioned. None of them came to Old Trafford, of course, and a number of Cantona’s friends believed they had been bandied only to pacify the one genuine star the club possessed: Éric himself. In an interview Marc Beaugé and I conducted in March 2009, Alex Ferguson admitted that – with the benefit of hindsight – he regretted not having been more forceful in his efforts to strengthen his squad at that time. And when I asked him if he thought it could have been a factor in Éric’s decision to call it quits a year hence, his answer was a plain ‘yes’. Cantona wished to prove himself on the European stage, which he wasn’t sure that United could help him do any more. Looking back, however, had he not been in a similar situation when he had found himself frozen out of the Marseille team four years previously? He could have chosen to walk out, but bided his time. Leaving would have been quitting, admitting defeat. He would not give his enemies the satisfaction of knowing that they had succeeded in hounding him out of England after they had made it impossible for him to live and play in France. And the children of Manchester played their part too.

The first of Éric’s 120 hours of community service was spent signing autographs at The Cliff, surrounded by the now familiar gaggle of cameramen, security personnel and hardcore fans, who were augmented that day – 18 April – by Liz Calderbank, a supervisor of the Manchester Probation Service, whose presence was the only reminder that Cantona was expiating a crime. It was he who had suggested that his time would be best employed coaching children from the Manchester area, and this he did over a period of three months, to the delight of some 700 boys and girls, the first of whom were a dozen players from Ellsmere Park Junior FC, aged 9–12. That club had no strip and no pitch to train and play on; in fact, it had barely come into existence, having been involved in a mere three games before Cantona took them under his wing for a two-hour session.

Few of the boys had managed to get a minute’s sleep the night before and couldn’t contain their excitement when the moment finally came to meet their idol in the club’s gymnasium. Paul Thompson, aged twelve, enthused: ‘We just ran up to him cheering. He was totally brilliant. I thought he would be a bit harsh, but he was great. I talked to him in French, and he told me not to get rough because I would be sent off.’ Journalists then moved on to Aiden Sharp, 11, and wrote in their notebooks: ‘He worked really hard and made us work the whole time. Éric was a very nice man, very patient and gentle. I’ve learnt tons from him today.’

The Times

had sent Rob Hughes to Salford, who heard another of the beaming children tell him: ‘He were [

sic

] terrific, showed me I could score. He told me to concentrate on one corner of the net, to aim for that, and now I score every time.’

Éric adored children, in whom he saw a reflection of his former and truer self, before he had been emotionally maimed by the corrupting power of professional football. He had said so himself on many occasions – he couldn’t be granted the privilege of being a child again, but playing brought him as close as could be to this unattainable aim. There, at The Cliff, the uncontrollable pupil, Guy Roux’s ‘

caractériel

’, turned into a patient guide for starstruck youngsters who could barely speak through the tears when the time came to leave their ‘King’ for good. ‘It was the best day of my life,’ one of them said, shaking with a mixture of grief and elation, wishing that tomorrow, and the day after that, and every other day, he could jump from his team’s minibus to meet his hero, distraught by the realization that this would never happen again. The haunting image of that boy’s face has never left me, and I don’t think it has left Cantona’s mind either. He truly loved every single one of these kids, and wasn’t playing to the audience when he said, later in the year: ‘It wasn’t a punishment. It was like a gift,’ adding after a half-thoughtful, half-mischievous pause a ‘thank you’ that, I believe, was partly but not entirely ironic, as it was certainly meant for the children he spent the end of the spring with as much as for the court that had ‘punished’ him. To one of them, ten-year-old Michael Sargent, he had confided that he ‘would really like to stay [at United]’. He owed them a debt, one that was light to carry, and that he was happy to honour. These children had ‘helped [him] a lot’, he said. Judging by the transformation of his character over the coming year, they clearly had. He had told a boy called Simon Croft: ‘If you’re going to get a yellow card, walk away and don’t argue with the referee,’ words that others like Célestin Oliver and Sébastien Mercier had drummed into him when he was a

minot

himself. At long last, he was about to take on board the advice he had been given, and I’m not so sure it would have been the case if he hadn’t had to pass it on to others.

Éric wouldn’t return to competitive football until 30 September 1995 at the earliest. Ahead of him lay five months of inactivity, boredom, rumours, and the odd trumpet lesson with John MacMurray, the Canadian principal of the Hallé Orchestra. He found he had limited gifts for this instrument, and soon moved on. Support came from unlikely sources, like the bass player of The Stranglers, his compatriot Jean-Jacques Burnel, who toyed with the idea of including a tribute to Éric in the band’s forthcoming twentieth anniversary tour. ‘[Cantona] has done more for Anglo-French relations than anyone since Brigitte Bardot,’ the punk musician said. ‘You English should be grateful for him.’ It’s true that Burnel had his own reasons for empathizing with Cantona: he had once attacked a spectator at a Stranglers gig: ‘He insulted my mother, so I put down my guitar, leapt off the stage and landed him in hospital.’ Incidentally, Burnel taught karate when he wasn’t playing with The Stranglers. Meanwhile, in France, the editor of

Paris-Match

magazine, Patrick Mahé, was putting the finishing touches to his book

Cantona au Bûcher

(‘Cantona at the Stake’), oddly described in its blurb as ‘an impassioned plea for the celebrated footballer against the anti-French hysteria of the Anglo-Londoners’. Make of that what you will.

As for football, by the end of April, a verbal agreement had been reached to extend Éric’s contract at Old Trafford – or so it seemed, as his agent Jean-Jacques Amorfini was still waiting for a written proposal. Éric, whose present deal was due to expire a year hence, would commit himself to Manchester United until the end of the 1997–98 season. Despite Amorfini’s warning that things ‘could take longer’, the papers which had predicted Cantona’s exit swiftly announced that a resolution could be achieved ‘within a few days’, and they were right. Éric put his signature to a new, improved three-year agreement (which would bring him £750,000 a year, and not £1m, as most contemporary sources had it) on the very day English football’s only other true foreign star of the time, Jürgen Klinsmann, headed back to his native Germany: 27 April. It was Éric’s first appearance in front of the media since his ‘sardines’ quip. He looked heavier, which wasn’t much of a surprise, as his weight tended to fluctuate wildly when he wasn’t playing regularly. There was even the hint of a double chin on the face that emerged from a candy-striped pink jacket Jeeves would have instantly removed from Bertie Wooster’s wardrobe. ‘I can forget everything,’ he told the press, ‘and we can win everything. We are bigger than the people who have sometimes been so hard and so wrong’ – among whom he obviously didn’t include himself.