Capone: The Life and World of Al Capone (22 page)

Read Capone: The Life and World of Al Capone Online

Authors: John Kobler

By nightfall the entire terrace was covered with brilliant blossoms.

Finally the lack of space made it necessary to festoon the trees and lamp posts in front of the house with wreaths, immortelles and hanging baskets.

In Cicero, as a mark of respect for the slain man, nearly every saloonkeeper kept his blinds drawn and his doors locked for two hours.

Riding behind the hearse with his family on the way to Mount Olivet Cemetery, his jowls dark with the ritual growth of stubble. Capone could take comfort from the knowledge that his brother had not died for nothing. The Klenha slate won the election by an enormous plurality.

At the inquest on Frank both Al and Charlie Fischetti declared that they could furnish no relevant information. A year earlier the state's attorney, inquiring into how gangsters obtained permits to carry guns, learned that the Capones got theirs from a Chicago justice of the peace, George Miller. The permits were revoked. Now, in the course of the inquest, it developed that Justice Emil Fisher of Cicero had reissued gun permits to the Capones for "self-protection."

Eddie Vogel kept his side of the bargain. On May 1, one month after the elections, Torrio and Capone launched, without interference, their first Cicero gambling house. the Hawthorne Smoke Shop, next to the Hawthorne Inn. Managed for them by Frankie Pope, it was primarily a floating handbook operating at different addresses under different names-the Subway, the Ship, the Radio. From time to time the police felt constrained for the sake of appearances to stage a raid. They always gave ample advance notice, whereupon the action would shift to one of the alternative addresses. At the original Hawthorne Smoke Shop an average of $50,000 a day was bet on horse races, and during the first years the house netted more than $400,000. The number of gambling establishments in Cicero grew to 161. With cappers drumming up trade at the entrance, with whiskey sold inside at 75 cents a shot, wine at 30 cents a glass and beer at 25 cents a stein, they ran full blast twenty-four hours a day every day. Many of them Torrio and Capone owned outright or controlled. In the latter case they kept a lieutenant on the premises both to protect the proprietor against interlopers and to collect their cut, which ranged from 25 percent to 50 percent of the gross. One of these independents, Lau- derback's, at Forty-eighth Avenue and Twelfth Street, catered to some of the country's wildest plungers, with as much as $100,000 riding on a single spin of the roulette wheel. The majority of the gambling dives, as well as of Cicero's 123 saloons, bought their beer, willingly or unwillingly, from the Torrio breweries.

The only influential Ciceronian who continued to defy Torrio and the O'Donnells was Eddie Tancl. He went on buying his beer whereever he wished. Early one Sunday morning, after an all-night spree, Myles O'Donnell and a drinking companion, Jim Doherty, staggered into Tancl's saloon and ordered breakfast. At a table across the room sat Tancl, his wife, his head bartender, Leo Klimas, and his star entertainer, Mayme McClain. Only one waiter, Martin Simet, was still on duty. The bill he brought O'Donnell and Doherty when they finished breakfast furnished the pretext they were looking for. They loudly complained that he had overcharged them.

Tancl came over to their table just as O'Donnell threw a punch at the waiter. The ex-prizefighter stepped between them. O'Donnell gave him a shove. At this the enmity that had been building up for months between the two men exploded. They both drew guns, fired simultaneously, and wounded each other in the chest. Doherty joined the combat, firing wildly. Simet and Klimas rushed him and tried to disarm him. A bullet from O'Donnell's gun sent Klimas crashing hack against the bar, dead.

O'Donnell and Tancl, still shooting at each other, fell, bleeding from several wounds, got up, resumed firing until their guns were empty. O'Donnell, pierced by four bullets, lurched out into the street, followed by Doherty. They ran off in opposite directions. Tancl, though mortally wounded, took another revolver from behind the bar and stumbled after O'Donnell, shooting as he went. His gun was empty when he overtook him two blocks from the saloon, and he hurled it at his head. The effort exhausted his last reserves of energy, and he fell to the street. So did O'Donnell. There they lay within reach of each other, but no longer able to move, the one dying, the other unconscious, when Simet arrived. "Get him," Tancl gasped. "He got me." They were his last words. Simet jumped up and down on the senseless O'Donnell, kicked him in the head, and left him for dead.

Jim Doherty, who had also been gravely wounded, dragged himself to a hospital. There the police brought the mangled O'Donnell, and after weeks of treatment both men recovered. Assistant State's Attorney William McSwiggin prosecuted them without success.

Such savagery earned Cicero a unique reputation. Mayor Klenha, injured in his civic pride, claimed it was grossly exaggerated. Cicero, he insisted, was no worse than Chicago; who could tell when one left Chicago and entered Cicero? A Chicago wag observed: "If you smell gunpowder, you're in Cicero."

"I don't know why they call me a hoodlum," Guzik once complained. "I never carried a gun in my life." He never did, or indulged in any violent deeds or language. His forte was accountancy, which he applied with brilliant results first to the brothel, then to the bootlegging business. As business manager of the Torrio-Capone syndicate and its No. 3 member, he reorganized it along the lines of a holding company. When Mayor Dever's police closed the Four Deuces, new headquarters were quietly set up two blocks away at 2146 South Michigan Avenue, a doctor's shingle-"A. Brown, MD" -nailed to the door and the front office furnished to resemble a doctor's waiting room. On shelves in the adjoining room stood row upon row of sample liquor bottles. Retailers prepared to place a large order could take a sample and have it analyzed by a chemist. In this way the syndicate built up a reputation as purveyors of quality merchandise.

The rest of Dr. A. Brown's office accommodated Guzik, his clerical staff and records of all the syndicate's transactions in six different areas. One group of ledgers listed wealthy individuals, hundreds of them, as well as the hotels and restaurants buying wholesale quantities of the syndicate's liquor; a second group of ledgers gave all the speakeasies in Chicago and vicinity that it supplied; a third, the channels through which it obtained liquor smuggled into the country by truck from Canada and by boat from the Caribbean; a fourth, the corporate structure of the breweries it owned or controlled; a fifth, the assets and income of its bordellos; a sixth, the police and Prohibition agents receiving regular payoffs.

The syndicate faced catastrophe in the spring of 1924, when, during a raid on 2146 South Michigan ordered by Dever and led by Detective Sergeant Edward Birmingham, these ledgers were seized. Guzik dangled $5,000 in cash under Birmingham's nose as the price of his silence. The detective reported the offer to his superiors. "We've got the goods now," Mayor Dever announced. But the rejoicing proved premature. Before either the state's attorney or any federal agency could inspect the incriminating ledgers, a municipal judge, Howard Hayes, impounded them and restored them to Torrio. Not a scrap of evidence remained on which to base a case.

On the evening of May 8, 1924, during a barroom argument, a free-lance hijacker named Joe Howard slapped and kicked Jake Guzik. Incapable of physical retaliation, the globular little man waddled off, wailing, to Capone. The outrage to his friend gave Capone additional cause to hunt down Howard, for the hijacker had also been overheard to boast how easy it was to waylay beer runners, including Torrio's. Capone found him half a block from the Four Deuces in Heinie Jacobs' saloon on South Wabash Avenue, chatting with the owner. At the bar two regular customers, George Bilton, a garage mechanic, and David Runelsbeck, a carpenter, were guzzling beer. As Capone swung through the doors, Howard turned with outstretched hand and called to him, "Hello, Al." Capone grabbed him by the shoulders, shook him, and asked him why he had struck Guzik. "Go back to your girls, you dago pimp!" said Howard. Capone emptied a six-shooter into his head.

After questioning Jacobs, Bilton and Runelsbeck, whose accounts of the slaying substantially agreed, Chief of Detectives Michael Hughes told reporters: "I am certain it was Capone," and he issued a general order for his arrest. The next day readers of the Chicago Tribune beheld for the first time a photograph of the face that would become as familiar to them as that of Calvin Coolidge, Mussolini or a Hollywood star. The newspaper, however, still hadn't got the name quite right. "Tony (Scarface) Capone," ran the caption, "also known as Al Brown, who killed Joe Howard. . . .

During the hours between the murder and the inquest two of the main witnesses underwent a change of memory. Heinie Jacobs now testified that he never saw the shooting, having gone into the back room to take a phone call when it occurred, and Runelsbeck claimed he would not be able to identify the killer. Bilton was missing.

The police held Jacobs and Runelsbeck as accessories after the fact and the inquest was adjourned for two weeks. With Capone still lying low, it was adjourned again. Then, on June 11, he sauntered into a Chicago police station, saying he understood he was wanted and wondered why. They took him to the Criminal Courts Building, where he was told why by the eager young assistant state's attorney, William H. McSwiggin, sometimes referred to, because of the numerous capital sentences he had obtained, as "the Hanging Prosecutor." For hours McSwiggin questioned Capone, who said he knew no gangsters and had never even heard of such people as Torrio, Guzik or Howard. He was, he insisted, a reputable businessman, a dealer in antiques.

The third and final session of the inquest took place on July 22. Jacobs and Runelsbeck, visibly terrified, added nothing to their pre vious testimony. The jurors' verdict: Joe Howard was killed by "one or more unknown, white male persons."

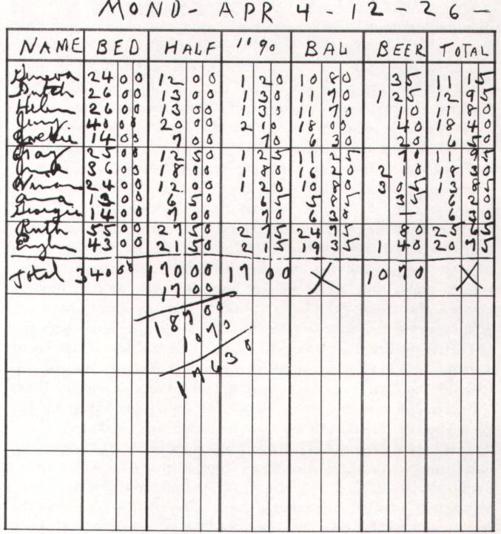

Torrio and Capone, faithful to their preelection promises, brought no more prostitutes to Cicero, but in the contiguous communities of Stickney, Berwyn, Oak Park and Forest View they instituted several brothels which, together with those they had established earlier, brought the total to twenty-two and the combined annual gross eventually to $10,000,000. The economics of these brothels were later revealed by records confiscated during a raid on the Harlem Inn in Stickney. They included day-by-day entries for each girl during a period of three weeks. The page reproduced on the next page covers twelve of the girls who were working on April 21, 1926.

When the customer had indicated his choice, a downstairs madam handed him a towel. The girl got another towel from an upstairs madam, who also assigned her a bedroom. The customer was charged $2 for every five minutes, or any fraction thereof, he spent with the girl. After the first five minutes the upstairs madam would knock and demand additional payment. If the customer was too absorbed to respond, she would sometimes walk in and thump him on the back.

Capone-led mobsters so thoroughly infiltrated one village on the Cicero border that it became known as Caponeville. Forest View was originally a farming community with a population of about 300. The idea of incorporating it as a village occurred to a Chicago attorney, Joseph W. Nosek, after he had spent several pleasant days there conferring with a farmer client over an impending lawsuit. A World War veteran and an official of the American Legion, Nosek described the bucolic charms of the place to a number of his fellow Legionnaires with a fervor that made them want to live there, and they agreed to support his project. Papers of incorporation were issued in 1924. A preamble to the village constitution dedicated Forest View "to the memory of our soldier dead so as to perpetuate their deeds of heroism and sacrifice." At the first village meeting Nosek was elected police magistrate and his brother John, president of the village board. For chief of police they chose one William "Porky" Dillon, who claimed to be an ex-serviceman. From the Cook County board the enthusiastic new villagers obtained enough free materials to pave their streets.

Soon after, Chief Dillon informed Magistrate Nosek that Al and Ralph Capone wanted to build a hotel and social club in Forest View. "I saw no harm," Nosek recalled later, "because I didn't know just who the Capones were. It looked like a good chance to improve our village."