Capone: The Life and World of Al Capone (56 page)

Read Capone: The Life and World of Al Capone Online

Authors: John Kobler

A good many Chicago gangsters, Capone among them, had been Jessel fans ever since 1926, when he plucked their heartstrings in that lachrymose drama of filial sacrifice, The Jazz Singer. In the last week of Hymie Weiss' life he accompanied his mother to the Harris Theater and by the third act was mingling his tears with hers. Capone, equally moved, sent Terry Druggan backstage to tell Jessel how much he wanted to shake his hand. "Call me Snorky," he said, when, after the performance a few nights later, curiosity brought the actor to the Metropole Hotel. Capone took him to supper at the Midnight Frolics. "Anything happens to you or any of your friends, you let me know," he said.

It was not an empty offer. With Bugs Moran's North Siders reduced by gunfire and jail sentences to a skeleton force and the Aiellos either dead or retired, no serious challenge to Capone's supremacy remained. Few gangsters now operated in Chicago without his knowledge, and fewer still without his approval. Thus, he was able to intervene when Jessel appealed to him in behalf of some colleague. Show folk were the natural prey of both extortioners who would threaten them with disfigurement unless they paid regular tribute, and of holdup men, who would lay in wait for them when they left the theater. Such victims, intended or actual, came to include Lou Holtz, Georgie Price, Rudy Vallee, Harry Richman-to name only a few.

Richman presented a particularly enticing target to predators, for he normally wore a small fortune in jewelry and carried at least one $1,000 bill with which it amused him to pay a restaurant or speakeasy tab and watch the waiter's eyebrows rise. During the Chicago run of George White's Scandals of 1927 he was waylaid between the Erlanger Theater and his hotel not once, but repeatedly. The next day he would buy a new jeweled cigarette case, rings, a watch, only to be robbed again. He finally went to see Capone, an admirer who had burst into his dressing room opening night, clapped him on the back, and cried: "Richman, you're the greatest!" Whispering some order to a henchman, Capone took the entertainer for a drive along the lakeshore. When they got back to the Lexington, a package lay on the mahogany office desk. It contained the missing jewelry and several thousand dollars. Capone also handed Richman a note, saying: "Put this in your pocket, and if you get into any trouble, use it." The note read: "To whom it may concern-Harry Richman is a very good friend of mine. Al Capone." Richman had occasion to use it a few nights later. The holdup men he showed it to apologized and withdrew.

While the impressionist Georgie Price was playing a Chicago vaudeville engagement, the jewelry and cash he left in his hotel room vanished. After Jessel spoke to Capone, that loot, too, was returned.

But the most dramatic recovery of stolen goods Capone ever brought about followed the appeal of a woman who had done him a small service, a Miss Mary Lindsay, the manager of a Washington, D.C., hotel. Driving through the Midwest on vacation, she had come upon a Chicago-bound train stalled just outside the city. Among the passengers pacing the track was Al Capone, whom she failed to recognize when he asked her for a lift. She drove him to the Lexington. Not until she glanced at the card he gave her, as he urged her to call on him for any help she might need while in Chicago, did she realize who the hitchhiker was. A few days later her purse, containing all her cash and traveler's checks, was snatched. She turned to Capone. That night, following his instructions, Miss Lindsay dined in a West Side cafe, taking the table facing the first of a line of stone columns. Midway through the meal, her purse suddenly appeared on the chair next to the column. Not a penny was missing.

On December 14, 1930, John Maritote, a twenty-three-year-old motion-picture operator and the younger brother of Frank Maritote, alias Diamond, whose wife was Rose Capone, married Mafalda Capone, age nineteen. It appears to have been a marriage of convenience for which neither bride nor groom could summon much enthusiasm. According to his friends, Maritote, who had hardly ever spoken to Mafalda, loved another girl, while Mafalda's heart was supposedly set on a boy she met in Miami. The internal politics of the Capone organization dictated the union. Frank Diamond, having risen to the top echelon, was demanding a bigger voice, especially when it came to the division of profits from bootlegging. By this second union between the two families Capone hoped to prevent dissension. He promised the couple $50,000 and a house as wedding presents.

Not since Angelo Genna was joined to Lucille Spingola had gangland witnessed such glittering nuptials. Three thousand guests, including Alderman William V. Pacelli, City Sealer Daniel Serritella, Jack McGurn, Frank Rio and the three Guzik brothers, packed St. Mary's Church in Cicero, and despite heavy snow and sleet, a thousand onlookers waited outside. Al Capone did not attend. With a vagrancy warrant issued by judge Lyle hanging over him, he had decided to return to Florida.

The matrons of honor, in pink duvetyn hats and pink chiffon gowns, were Mmes. Al and Ralph Capone. The bride, wearing a Lanvin model of ivory satin with a 25-foot train, walked down the aisle on the arm of brother Ralph. After the Reverend Crajkowski pronounced the couple man and wife, they adjourned with their families and guests to the Cotton Club, a Cicero nightclub that Ralph ran. The wedding cake, shaped like an ocean liner, measured 9 feet long, 4 feet high and 3 feet wide, and the prow bore the name in red icing of the newlyweds' honeymoon destination-Honolulu.

Only one slight contretemps had marred the proceedings. Detectives Mike Casey and Louis Capparelli from the state's attorney's office arrested five Caponeites claiming to be ushers. "Not ushers," said Casey, as they marched them off to the station house. "Shushers. They had guns in their pockets."

From Florida Capone submitted, through George Barker of the Teamsters' Union, a proposal to Chief Justice McGoorty, which the latter described, with signal restraint, as "cool effrontery." He offered to surrender on the vagrancy warrant, quit labor racketeering, leave Chicago, and operate his other enterprises by remote control. His conditions: dismissal of the vagrancy charge the moment he surrendered; no interference with his liquor business.

What the chief justice said to Barker is not recorded, but he told the grand jury: "[Capone's] most formidable competitors have been ruthlessly exterminated and his only apparent obstacle towards undisputed sway is the law. Such a trade is unthinkable. The time has come when the public must choose between the rule of the gangster and the rule of law."

THE office space allocated to Wilson in the old Federal Building was a windowless cubicle so cramped that he could hardly stir without brushing against the filing cabinet or another agent. For weeks, during the summer of 1930, he had closeted himself there, combing through mountains of papers seized by the police in raids on various Capone establishments as far back as 1924, through bank records, through the memoranda of his assistant agents, in quest of evidence linking Capone to the source of his profits. Wilson, Tessem and Hodgins between them had examined close to 1,700,000 separate items.

It was past midnight. Exhausted, discouraged, his vision blurred, he began gathering up the material strewn over the desk, chairs and floor to return it to the filing cabinet. Bending over to retrieve a bundle of checks, he bumped into the cabinet, and the drawer flew shut, locking automatically. He couldn't find the key. In the corridor stood a row of dusty old filing cabinets and seeing an open drawer, he decided to store the material there temporarily. The drawer was partly filled by a large package tied up in brown paper, one of many turned over to him by the state's attorney, which he had somehow overlooked. He broke the string. Out tumbled three black ledgers with red corners. They were dated 1924-26. Leafing through them, he stopped, electrified, at a page in the second ledger. The columns were headed BIRD CAGE, 21, CRAPS, FARO, ROULETTE, HORSE BETS.

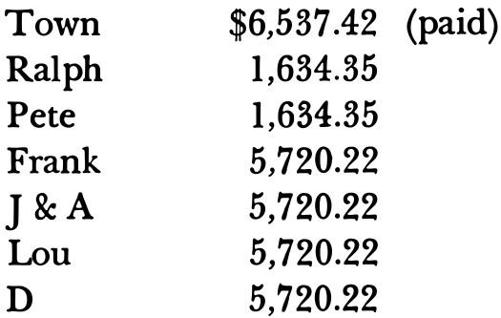

He was no longer exhausted. He carried the ledgers to his desk and began analyzing them entry by entry. They showed net profits totaling, in an eighteen-month period, more than $500,000. Every few pages a balance had been taken and divided among "A" (for Al, Wilson surmised), "R" (Ralph Capone), "J" (Jake Guzik), etc. A balance of $36,687 on December 2, 1924, had been divided as follows:

Wilson took "Town" to mean Cicero officials; "Pete," probably Pete Penovich, the first Smoke Shop manager; "Frank," Frankie Pope; "J & A," Jake and Al; "Lou," perhaps Louis La Cava; "D"? A notation at the foot of the page read: "Frank paid $17,500 for Al."

From the state's attorney's office, to which Wilson hastened in the morning, he learned that the ledgers were among those seized during the Smoke Shop raid after the McSwiggin murder in 1926. They were written in three different hands. Wilson and his teammates undertook the enormous task of comparing them with every specimen of gangsters' handwriting--they could collect from such sources as the motor vehicle bureau and other licensing agencies, banks, bail bondsmen, the criminal courts. Eventually a bank deposit slip turned up with a signature that matched the writing in numerous ledger entries between 1924 and 1926. It belonged to Leslie Adelbert Shumway, familiarly called Lou, who had preceded Fred Ries as cashier at the Ship.

While Wilson was trying to track down Shumway, a tipster repeated to him the comment of a Capone lieutenant: "The big fellow's eating aspirin like it was peanuts so's he can get some sleep."

Mattingly and Wilson conferred several more times. The lawyer conceded that his client's enterprises had produced income, though a relatively modest one. Wilson asked him to specify just how much in writing. To his amazement and joy, Mattingly submitted this statement "Re Alphonse Capone":

Taxpayer became active as a principal with three associates at about the end of the year 1925. Because of the fact he had no capital to invest in their various undertakings, his participation during the entire year 1926 and the greater part of 1927 was limited. During the years 1928 and 1929, the profits of the organization of which he was a member were divided as follows: one-third to a group of regular employes and one-sixth to the taxpayer and three associates... .

I am of the opinion that his taxable income for the years 1926 and 1927 might be fairly fixed at not to exceed $26,000 and $40,000, respectively, and for the years 1928 and 1929, not to exceed $100,000 per year.

As Wilson knew, Capone spent more than $100,000 a year on high living alone. But however remote from the truth, here was a written admission of tax delinquency. Mattingly made it "without prejudice to the rights of the above named taxpayer in any proceedings that might be instituted against him. The facts stated are upon information and belief only." He miscalculated. No such stipulation was legally binding, and Wilson gleefully added the statement to Case Jacket SI-7085-F.

Harking back to the investigation many years later, Wilson revealed the identity of a man he considered to have been his single most valuable secret ally. This was the St. Louis lawyer and dog track operator Edward O'Hare. Their mutual friend, John Rogers of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, brought them together at lunch in the Missouri Athletic Club. "He wanted to look you over," he told Wilson afterward. "He's satisfied," and he explained that O'Hare had decided to inform against Capone. His motive was paternal. With his son's heart set on Annapolis he hoped to smooth the way for him by helping the government topple Capone. Did he understand the risk? Wilson asked. If O'Hare had ten lives, Rogers replied, he would gladly risk them all for the boy.