Carrion Comfort (108 page)

Authors: Dan Simmons

Jackson leaned forward and said softly next to Natalie’s ear, “Do you really think they’re going to let us land?”

Natalie set her cheek against the window. “If the old woman does what she said she would. Maybe.”

Jackson snorted a laugh. “You think she will?”

“I don’t know,” said Natalie. “I just think it’s more important that we get Saul out. I think we did everything we could to show Melanie that it was in her self-interest to act.”

“Yeah, but she’s crazy,” said Jackson. “Crazy folks don’t always act in their own self-interest, kid.”

Natalie smiled. “I guess that explains why we’re here, huh?”

Jackson touched her shoulder. “Have you thought about what you’re going to do if Saul’s dead?” he asked softly.

Natalie’s head moved up and down an inch. “We get him out,” she said. “Then I go back and kill the thing in Charleston.”

Jackson sat back, curled up in the backseat, and was breathing loudly in his sleep a minute later. Natalie watched the ocean until her eyes hurt and then turned toward the pilot. Meeks was looking at her strangely. Confronted with her stare, he touched his baseball cap and turned his attention back to the glow of the instruments.

Wounded, bleeding, fighting just to stay standing and conscious, Saul was pleased to be precisely where he was. His gaze never left the Oberst for more than a few seconds. After almost forty years of searching, he— Saul Laski— was in the same room as Oberst Wilhelm von Borchert.

It was not the best of situations. Saul had gambled everything, even allowing Luhar to overpower him when he

could

have gotten to his weapons in time, on the slim hope of being brought into the Oberst’s presence. It was the scenario he had shared with Natalie months earlier as they sat drinking coffee in the orange-scented Israeli dusk, but these were not optimum conditions. He would have a chance of confronting the Nazi murderer only if Willi were the one to use his psychic abilities on Saul. Now all of the mutant throwbacks were there— Barent, Sutter, the one named Kepler, even Harod and Melanie Fuller’s surrogate— and Saul was terrified that one of

them

would attempt to seize his mind, squandering the single, slim chance he might have to surprise the Oberst. Then there was the fact that in his scenario to Natalie, Saul had always painted the picture of a one-to-one confrontation with the old man, with Saul being the physically stronger of the two. Now Saul was using most of his strength of will and body just to remain standing, his left hand hung bleeding and useless, and there was a bullet lodged somewhere near his collarbone, while the Oberst sat looking fit and rested, thirty pounds heavier in muscle than Saul and surrounded by at least two superbly conditioned cat’s-paws with at least half a dozen other people nearby whom he could use at will. Nor did Saul believe that Barent’s security people would allow him to take more than three unauthorized strides before they gunned him down in cold blood.

But Saul was happy. There was no place else in the world he would rather be.

He shook his head to focus his attention on what was happening. Barent and the Oberst were seated while Barent set the human chess pieces in place. For the second time in that endless day, Saul had a waking hallucination as the Grand Hall shimmered like a reflection on a wind-rippled pond and suddenly he saw the wood and stones of a Polish keep, with gray-garbed

Sonderkommandos

taking their plea sure under centuries-old tapestries while the aging

Alte

sat huddled in his general’s uniform like some wizened mummy wrapped in baggy rags. Torches sent shadows dancing across stone and tile and the shaven skulls of the thirty-two Jewish prisoners standing at tired attention between the two German officers. The young Oberst brushed his blond hair off his forehead, propped his elbow on his knee, and smiled at Saul.

The Oberst smiled at Saul. “

Willkommen, Jude

,” he said. “Come, come,” Barent was saying, “we shall all play. Joseph, you come here to king’s bishop three.”

Kepler stepped back with an expression of horror on his face. “You have to be fucking kidding,” he said. He backed into the bar table hard enough to topple several bottles.

“Oh, no,” said Barent, “I am not kidding. Hurry, please, Joseph. Herr Borden and I wish to settle this before it gets too late.”

“Go to

hell

!” screamed Kepler. He clenched his fists as cords stood out in his neck. “I’m not going to be used like some fucking surrogate while you . . .” Kepler’s voice cut off as if a needle had been pulled from a faulty record. The man’s mouth worked a second, but not the faintest hint of sound emerged. Kepler’s face grew red, then purple, and then darkened toward black in the seconds before he pitched forward onto the tiles. Kepler’s arms seemed to be jerked behind him by brutal, invisible hands, his ankles bound by invisible cords, as he propelled himself forward by a spastic, humping, flopping action— a disturbed child’s idea of a worm’s locomotion— his chest and chin slamming onto the tile with each absurd spasm. In this way, Joseph Kepler inched his way on his face and belly and thighs across twenty-five feet of open floor, leaving streaks of blood from his torn chin on the white tiles, until he arrived at the king-bishop-three square. When Barent relaxed his control, Kepler’s muscles visibly twitched and spasmed in relief, and there was a soft sound as urine soaked the man’s pant leg and flowed onto the dark tile.

“Stand up, please, Joseph,” Barent said softly. “We want to start the game.”

Kepler pushed himself to his knees, stared in shock at the billionaire for a moment, and silently stood on shaky legs. Blood and urine stained the front of his expensive Italian slacks.

“Are you going to Use all of us like that, Brother Christian?” asked Jimmy Wayne Sutter. The evangelist was standing at the edge of the improvised chessboard, the light from the overhead spots gleaming on his thick, white hair.

Barent smiled. “I see no reason to Use anyone, James,” he said. “Provided they do not become an obstacle to the completion of this game. Do you, Herr Borden?”

“No,” said Willi. “Come here, Sutter. As my bishop, you are the only surviving piece other than kings and pawns. Come, take your place here next to the queen’s empty square.”

Sutter raised his head. Sweat had soaked through his silk sports coat. “Do I have a choice?” he whispered. His theater-trained voice was raw and ragged.

“

Nein,

” said Willi. “You must play. Come.”

Sutter turned his face toward Barent. “I mean a choice in which side I serve,” he said.

Barent raised an eyebrow. “You have served Herr Borden well and long,” he said. “Would you change sides now, James?”

“ ‘I find no plea sure in the death of the wicked,’ ” said Sutter. “ ‘Believe in the Lord Jesus Christ and ye shall be saved.’ John 3:16, 17.”

Barent chuckled and rubbed his chin. “Herr Borden, it seems that your bishop wishes to defect. Do you have any objections to his ending the game on the black side?”

The Oberst’s face bore the petulant expression of a child. “Take him and be damned,” he said. “I don’t need the fat faggot.”

“Come,” Barent said to the sweating evangelist, “you shall be at the king’s left hand, James.” He pointed to a white tile one space advanced from where the black king’s pawn would have begun the game.

Sutter took his place on the board next to Kepler.

Saul allowed himself a glimmer of hope at the thought that the game might proceed without the mind vampires using their power on their pawns. Anything to defer the moment when the Oberst would touch his mind.

Leaning forward in his massive chair, the Oberst laughed softly. “If I am to be denied my fundamentalist ally,” he said, “then it amuses me to promote my old pawn to the rank of bishop.

Bauer, verstehts Du

? Come, Jew, and accept your miter and crook.”

Quickly, before he could be prompted, Saul moved across the lighted expanse of tile to the black square in the first rank. He was less than eight feet from the Oberst, but Luhar and Reynolds stood between them while a score of Barent’s security people scrutinized every step he took. Saul was in great pain from his wound now— his left leg was stiff and aching, his shoulder a mass of flame— but he tried to show none of this as he strode forward.

“Like old times, eh, pawn?” the Oberst said in German. “Excuse me,” he added. “I mean, Herr

Bishop.

” The Oberst grinned. “Quickly, now, I have three pawns remaining. Jensen, to K1,

bitte.

Tony, to QR3. Tom will serve as pawn in QN5.”

Saul watched as Luhar and Reynolds took their places. Harod stood where he was. “I don’t know where the fuck QR3 is,” he said.

The Oberst beckoned impatiently. “The second square in front of my queen rook’s tile,” he snapped.

“Schnell.”

Harod blinked and lurched toward the black square on the left side of the board.

“Fill your last three pawn spaces,” the Oberst said to Barent.

The billionaire nodded. “Mr. Swanson, if you don’t mind. Next to Mr. Kepler, please.” The mustached security man looked around, set down his automatic weapon, and walked to the black square to the left and rear of Kepler. Saul realized that he was a king knight’s pawn who had not yet moved from his original square.

“Ms. Fuller,” said Barent, “if you would allow your delightful surrogate to proceed to the queen rook’s pawn original position. Yes, that is correct.” The woman who had once been Constance Sewell stepped gingerly forward on bare feet to stand four squares in front of Harod. “Ms. Chen,” continued Barent, “next to Miz Sewell, please.”

“No!” cried Harod as Maria Chen stepped forward. “She doesn’t play!”

“

Ja

she does,” said the Oberst. “She brings a certain beauty to the game,

nicht wahr

?”

“No!” Harod screamed again and pivoted toward the Oberst. “She’s not part of this.”

Willi smiled and inclined his head toward Barent. “How touching. I suggest that we allow Tony to trade places with his secretary if her pawn position becomes . . . ah . . . threatened. Is that agreeable to you, Herr Barent?”

“Yes, yes, yes,” said Barent. “They can exchange places when and if Harod wishes, as long as it does not disrupt the flow of the game. Let’s get on with it. We still need to set our kings in place.” Barent looked at the remaining clusters of aides and security people.

“

Nein

,” called the Oberst, standing and walking onto the board. “

We

are the kings, Herr Barent.”

“What are you talking about, Willi?” the billionaire asked tiredly.

The Oberst opened his hands and smiled. “It is an important game,” he said. “We must show our friends and colleagues that we support their efforts.” He took his place two squares to the right of Jensen Luhar. “Besides, Herr Barent,” he added, “the king cannot be captured.”

Barent shook his head but stood and walked to the Q3 position next to the Reverend Jimmy Wayne Sutter.

Sutter turned vacant eyes toward Barent and said loudly, “ ‘And God said unto Noah, The end of all flesh is come before me; for the earth is filled with violence through them; and, behold, I will destroy them with the earth . . .’ ”

“Oh, shut the fuck up, you old queer,” called Tony Harod. “Silence!” bellowed Barent.

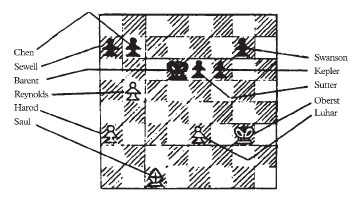

In the brief absence of noise that followed, Saul tried to visualize the board as it stood at the end of Move 35:

The direction of the end game was too complicated to predict with Saul’s modest chess ability— he knew that he was about to witness a contest between masters— but he could sense that Barent had gained a strong advantage in recent moves and seemed confident of a win. Saul failed to see how the Oberst’s white could achieve much more than a draw with even the best of play, but he had heard the Oberst say that a draw would constitute a victory for Barent.

One thing Saul did know: as the sole surviving important piece in a field of three pawns, the bishop would be used extensively, even if at great risk. Saul closed his eyes and attempted to withstand the sudden, resurgent waves of pain and weakness.

“All right, Herr Borden,” Barent said to the Oberst. “It is your move.”

Melanie

W

illi and I consummated our love that mad evening. After all those years.

It was through our catspaws, of course, prior to our arrival at the Manse. Had he suggested such a thing, or even hinted at it before acting, I would have slapped his face, but his agent in the form of the giant Negro offered no preliminaries. Jensen Luhar grasped Miss Sewell by the shoulders, pushed her forward to the soft grass in the darkness under the oaks, and brutally had his way with her. With us. With me.

Even while the Negro’s heavy weight still lay atop Miss Sewell, I could not help but recall those whispered conversations between Nina and me during our teenage slumber parties, when the worldly-wise Nina would tell me breathless and obviously overheard stories about the supposed exaggerated anatomy and prowess of colored men. Seduced by Willi, still pinned facedown to the cold ground by Jensen Luhar’s weight, I returned my awareness from Miss Sewell to Justin before remembering, in my dazed state, that Nina’s colored girl had said that she was not from Nina at all. It was good that I knew the girl had been lying. I wanted to tell Nina that she had been right . . .

I do not relate this casually. Except for my unexpected and dreamlike interludes via Miss Sewell in the Philadelphia hospital, this was my first such experience with the physical side of courtship. However, I would hardly call the rough exuberance of Willi’s man an extension of courtship. It was more like the frenzied spasms of my aunt’s male Siamese when it seized a hapless female who was in heat through no fault of her own. And I confess that Miss Sewell seemed to be in constant heat since she responded to the Negro’s rough and almost non ex is tent overtures with an instant lubricity that no young lady of my generation would have allowed.

At any rate, any reflection or response to this experience was further cut short by Willi’s man suddenly pushing himself upright, his head swiveling in the night, his broad nostrils flaring. “My pawn approaches,” he whispered in German, He pressed my face back to the ground. “Do not move.” And with that, Willi’s surrogate had scrambled into the lower branches of the oak tree like some great, black ape.

The absurd confrontation that followed was of little importance, resulting in Willi’s man carrying Nina’s supposed surrogate, the one called Saul, back to the Manse with us. There was one magical moment when, seconds after Nina’s poor wretch was subdued and before the security people surrounded us, all of the external spotlights and floodlights and softly glowing electric lanterns in the trees were switched on and it was as if he had entered a fairy kingdom or were approaching Disneyland via some secret, enchanted entrance.

The departure of Nina’s Negress from my home in Charleston and the nonsense that followed distracted me for a few minutes, but by the time Culley had carried in Howard’s unconscious form and the body of the colored interloper, I was ready to return my full attention to my meeting with C. Arnold Barent.

Mr. Barent was every inch a gentleman and greeted Miss Sewell with the deference she deserved as my representative. I sensed immediately that he saw through my catspaw’s sallow veil to the face of mature beauty beneath. As I lay on my bed in Charleston, bathed in the green glare of Dr. Hartman’s machines, I knew that the feminine glow that I was feeling somehow had been accurately transmitted through the rough dross of Miss Sewell to the refined sensibilities of C. Arnold Barent.

He invited me to play chess and I accepted. I confess that until that moment, I had never held the slightest interest in the game. I had always found chess to be pretentious and boring to watch— my Charles and Roger Harrison used to play regularly— and I had never bothered to learn the names of the pieces or how they moved. More to my liking had been the spirited games of checkers contested between Mammy Booth and myself during the rainy days of my childhood.

Some time passed between the beginning of their silly game and the point of my disillusionment with Mr. C. Arnold Barent. Much of the time my attention was divided as I sent Culley and the others upstairs to make preparations for the possible return of Nina’s Negress. Despite the inconvenience, it seemed the appropriate time for me to set into motion the plan I had conceived some weeks earlier. During the same period, I continued to maintain contact with the one I had watched for so many weeks during Justin’s outings along the river with Nina’s girl. At this point I had abandoned plans to use him as directed, but maintaining the charade of consciousness with him had become an ongoing challenge because of the visibility of his position and the complexities of the technical vocabulary at his command.

Later, I would be more than a little pleased that I had taken the effort to maintain this contact, but at the time it was merely another annoyance.

In the meantime, the silly chess game between Willi and his host progressed like some surreal scene expurgated from the original

Alice in Wonderland.

Willi shuffled back and forth like a well-dressed Mad Hatter as I allowed Miss Sewell to stand and be moved occasionally— always trusting in Mr. Barent’s promise that she would not be placed in harm’s way— while the other pitiful pawns and players marched to and fro, captured others, were captured in return, died their unimportant little deaths, and were removed from the board.

Until the instant Mr. Barent disappointed me, I paid little attention and had little involvement in their boys’ game. Nina and I had our own contest to complete. I knew that her Negress would be back before sunrise. As tired as I was, I hurried to make things ready for her return.