Carry Me Home (100 page)

Authors: John M. Del Vecchio

Wherever, whenever his ears told him, Bobby would raise his head, gesture toward town, “Hear that bell?” he’d ask. “That’s St. Ignats. This town’s got to know who we are, who we were. Not who they thought we were, not who they think we were because they saw

Apocalypse Now

or

The Deer Hunter

or

Rambo

, or 1st Witness News.”

The expansion of unstuck vets, of the unstuck microcosmic community, grew into the larger community not simply as a business element like EES or Kinnard/Chassion or even the Mall, but as one-on-one volunteers helping the elderly, tutoring school children—especially “problem kids” of which and for which the vets both had a special understanding and an affinity, coaching in-town youth basketball, soccer and hockey, joining the PTA, the Rotary and Chamber of Commerce (after all, EES was now the sixth-largest company in town), helping the financially disabled—particularly with the reconstruction—plumbing and heating—of their homes, volunteering for church or temple functions which lead to assisting St. Ignatius with the sponsoring of the Huynh Thanh family, and finally to opening up High Meadow, the institute, the library, the mock trials.

Where we helped others, others helped us. Pop helped Linda and me buy a house in Old New Town. After ten years in the apartment in Creek’s Bend, Gina and Michelle finally had rooms of their own, Linda had her study, we all had a rec room, and there was a yard where we planted trees and expected to watch them grow for fifty years.

Call it reaching out. Sara, Linda and Emma expanded their women’s group, opening it to any abused woman. And as a Viet Nam vet group we began networking with other Viet Nam vet groups—first in Pennsylvania, then Texas, California, North Carolina, the entire country. We may have or may not have had the most comprehensive program but we were not a unique grouping. Viet Nam veteran groups were springing up all over America. By 1980 the movement was a snowball turned avalanche.

On July Fourth the bells of St. Ignatius rang while we marched as a unit in the town’s parade. We had a strack color guard unit but behind we were loose, having fun, tossing candy into the crowd, handing out American flag decals, letting the children come out and pet our mascots—Bobby’s Josh and the nucleus of my new agricultural venture, three Viet Namese potbellied pigs. (We’d dressed them in blue uniforms provoking hoggy snorts from the pigs and squeals of laughter from Jessie Taynor.)

On the 5th the bells rang again marking the arrival of the Huynh family and of Vu Van Hieu, a lone boat person, a CPA, a man who, after years of communist reeducation camps, repeated escape attempts, and a year in a Thai refugee camp, had finally reached the relocation center at Indian Town Gap only to lose his sponsor. Bobby hired him unseen.

This was a happy time—perhaps the happiest and most fulfilling in Bobby’s life. Frankie “The Kid” Denahee, our 128th vet, came, brought with him the sad news of Fuzzy and Wildman. Still T-n-T and The Kid were together. I had to step back in time with them, as Bobby taught, becoming a ladder, giving them the ability to move on without taking from them the ability to return. All year I had been chided about the tunnel, the bomb shelter. Frankie joined right in.

Lea Balliet, Linda’s youngest sister, came to visit, to sing and entertain. She was as pretty as Linda, maybe prettier. At twenty-two she drove the guys wild—so naive, so innocent, she’d been only eight or ten when most of us had been in Viet Nam. Marcus came, too. And Lem, the Tunesmyth. And Lee, Corky, Spider, Steve all the way from Idaho, Big Don, and Chuck in Jody’s Cadillac—entertainers all of them, bringing their guitars, their music, their bands—veterans, all of them.

Later Bobby would look back and tag the year between the first raid and the next onset The Help Years, and he would snarl that the destruction of The Help Years had begun the week of Monday, 7 July 1980, with the letter he received from the IRS, and with the revolt of the excluders, and with the blood.

T

HE WIND BLEW COLD.

The street was empty. He lifted the receiver, dialed the number. Snowflakes fluttered in the lee of the open booth. The sky was gray, not yet dark, late January, late afternoon.

“Internal Revenue Service. Criminal Investigations. Gilmore.”

“Yes.” He altered his voice. “I’m—I’m calling about one of your programs.”

“Uh-huh.”

“I’m calling about the program you’ve got for turning people in for tax evasion.”

“Yes.”

“You give rewards, right?”

“There’s a program ...”

“Percentage, right?”

“That can be arranged. Who am I speaking with?”

“No. I—I can’t tell you that. I’m talking the anonymous program. I know you do that.”

“In substantial cases ...”

“That’s what I’m talking here. Major fraud. Big time evasion. Maybe a hundred thousand. Maybe a million. None of the penny ante stuff.”

“Can you hold, please?”

“What? No!”

“Excuse me?”

“I’m calling from a pay phone. Don’t try to identify me.”

“No.” In the agent’s voice there was irritation, boredom, apathy. “I’m just getting a file to issue you a number. When you call, identify yourself by the number.”

“How do I get paid?”

“To bearer. Sent to a post office box.”

“Yeah. Yes. That’s what I want.”

“Can you give me some information?”

“First give me a number.”

“Okay. Your number is

R

as in Romeo,

T

as in Tango,

L

as in Lima, six, seven, six, four. Do you want to repeat it back to me?”

“R. T. L. Six. Seven. Six. Four.”

“Now, tell me who we’re talking about.”

“First tell me who you are.”

“I’m Special Agent Stan Gilmore.”

“Mr. Gilmore?”

“Um-hmm.”

“Keep this file open. This is going to be big. I’ll call again.”

Monday, 7 July 1980—

Round and round the mulberry bush

The monkey chased the weasel,

The monkey thought it was a-all in fun,

POP! goes the weasel.

The song was in his head, swirling, mixed with other immediate demands and concerns, new and old, swirling like flakes in a winter storm, Peppin, Zarichniak and Denahee, all, all morning, pulling at him, joy-terror-fear-questioning.

It was Noah’s first day of summer camp, first time on a bus, alone, going off without Sara or Bobby, without Linda or one of the vets. It had taken three months for his night terrors to abate, six for the acting out to subside, nine for him to again appear the confident little boy he’d been before the raid. Bobby thought of him at breakfast. Sara and Am had been upstairs. “What did the monkey say?” Noah had asked.

“I don’t think the monkey said anything,” Bobby’d answered. “Only the weasel. He goes—” Bobby put his right index finger into his mouth, blew up his cheeks, “Pop!” Bobby smiled.

“But Papa, why didn’t the monkey say anything?”

“I don’t know, Noah,” Bobby said. “That’s not part of the song. Just, ‘the monkey thought it was aaa-lll in fun. Pop! goes the weasel.’”

“What did the weasel think?”

“He was being chased by the monkey.”

“But,” Noah persisted, “what did he think?”

“I think he thought it was fun too. Don’t you think it’s a fun song?”

Noah hadn’t answered. Paulie, too, had been quiet, but he was always quiet unless he had something to say. Bobby wasn’t worried about him. Somehow, perhaps because of age or because he’d screamed through most of it and thusly had not seen much, the raid had seemingly not traumatized him.

“Noah?” Bobby said.

“I don’t know,” the boy answered quietly. “I just wanted to know what the weasel thought. That’s all.”

“Hmm.” Bobby had been about to continue when Sara came down with Am dressed in a yellow sunsuit and a big yellow sunbonnet.

“He’s going to miss the bus,” Sara had said to him. Then to Noah, “You don’t want to miss the bus on the first day, do you?”

The bus had come. Sara and Bobby, Paul, Am and Josh had all accompanied Noah on the long walk down the drive. Then quickly Noah, never before having even been in a school bus, scrambled up the stairs as if he’d commuted that way for years. In seconds the bus had gone. Then Paulie had burst into tears because he couldn’t go too.

Bobby was not focused on the here and now. He was checking in Frankie “The Kid” Denahee, the 128th vet, the ex-roofrat, ex-gunbunny. Vu Van Hieu was at a small desk in one corner, bent over the master ledger, entering figures in his impeccable hand. It had taken him one day to learn Bobby’s system. Carl Mariano was at a second desk that had displaced Van Deusen’s drawing table. A third desk was empty. Bobby looked at Denahee, continued talking, not listening to his own words but blabbing on automatic. “We’re brought up with the dual concept sane-insane. But, like in so many seeming logical tautologies it narrows the field and restricts our view of reality. So here we add

a-sane

, meaning without sanity, or beyond the bounds of reason, but not meaning weird or deranged or crazy. Asane, like baseball, the color green, dreams, intrusive day thoughts. Your reaction, your feelings, like most of us here, are normal and extraordinary. The circumstances, the events you’re reacting to were extraordinary....”

Bobby bent over the organization chart of High Meadow. There were now sixty-eight vets in residence—one of Asian heritage, one indigenous American, six Hispanics, ten of African ancestry, and fifty genetically European or Middle Eastern. The main office or headquarters consisted of Bobby, Tony, Carl, Don Wagner and now Vu Van Hieu. Tony also headed the column titled The Farm. Beneath him, with specific titles, were Thorpe, Treetop, Renneau, Cannello, and Rifkin, then eleven others. Van Deusen (design), Gallagher (construction/installations), Bechtel (assembly), and Mohammed (sales) headed the thirty-seven-man EES unit. Sherrick and Hacken plus five more ran The Institute; and in a new structure, Family Services, two vets assisted Sara, Emma, and occasionally Linda.

“Um ... Where was I? Oh ... ah, for now I’m going to list you under Tony’s command, okay?”

“Sure.”

“Did I mention to you about the grand jury indictments?”

“I didn’t really get that.”

“They’re deciding who to indict. Last year’s trial was of the five administrations starting with Eisenhower. The guys have been working on this year’s candidates for some time. Maybe Ngo Dinh Diem, Ho Chi Minh, Sihanouk, or Jane Fonda. They get pretty lively....”

Again his mind shifted to automatic, the conversation running now here, now there, routine chatter. “Your first ten dollars each week automatically goes into your education fund. After you’re settled you’ll start classes....” Bobby’s eyes shifted just an inch, just enough to look away from Frank Denahee to a stack of mail. A second stack held letters from veterans who wanted to come to High Meadow—or from relatives who wanted to send them. Where to put them? How to support them, have them support themselves? The place was bursting at the seams. The drive was lined with private cars, trucks—many old, rusted, mechanically defunct, making the farm look more like Johnnie Jackson’s Auto Salvage than the pristine mountain meadow farm he’d known as a boy.

“You were talking about classes that are available downtown ...”

“Oh yeah. There’s things we can do up here but there are things we can’t. Couple of guys who were medics are taking nursing courses—”

“Ha!” Denahee snickered. “To change bedpans!”

Bobby’s face turned to stone. For a second he repressed an agitation that wanted to blow, then he released. “Don’t be an idiot! Don’t act like some stupid, spoiled school brat. If you’re interested, we’ll get up into a good course. Aim for RN. Specialize in emergency room care. Or ICU. Shit. I don’t care what you study. Everyone here studies. Quality counts. You come to me, you come voluntarily. We’ll take you in but you’ve got to follow the rules, you’ve got to strive. Look where you’re at! No money. Never learned how to handle it. You told me that yourself. Trouble keeping a relationship. Right? We’re going to confront that. It doesn’t do any good teaching a guy a skill and having him get a job if all he’s going to do is blow his pay. Fact is, you don’t know how to live in this society.”

Vu and Mariano popped their heads up from their work. Carl had never heard Bobby take this tone, this early. Bobby snapped. “You’re number one twenty-eight. Not one guy who’s stayed through a year has fucked up again on the outside. This is basic, modern life skills. You listen in class. You take notes. Part of our in-processing is reading evaluation. If you score low, it’s mandatory you take Sara’s reading class. Mandatory. The circuit includes nutrition. If you put enough shit into your mouth, sooner or later all you can talk or think is shit. Your outcome depends on your attitude ... but I guarantee ... if you put in the effort, it’ll turn your life around.” Bobby puffed, exhausted. He dismissed Denahee, sat slumped, slouched, in his chair, angry beyond reason.

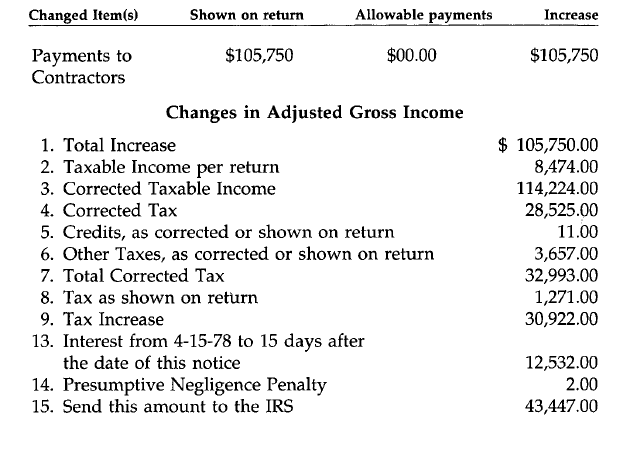

All day waves of agitation rolled over him, receded. His thoughts jumped from project to project, then back to the song, the conversation with Noah, the boy getting on the bus. What effect will it have on him? he thought as he sorted the mail, passed invoices and checks to Hieu, inquiries to Carl. He hefted a letter from the Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, split the envelope with a North Viet Namese Army bayonet a new vet, Michael Yasinsky, had given him. The letter’s type was small, closely packed.