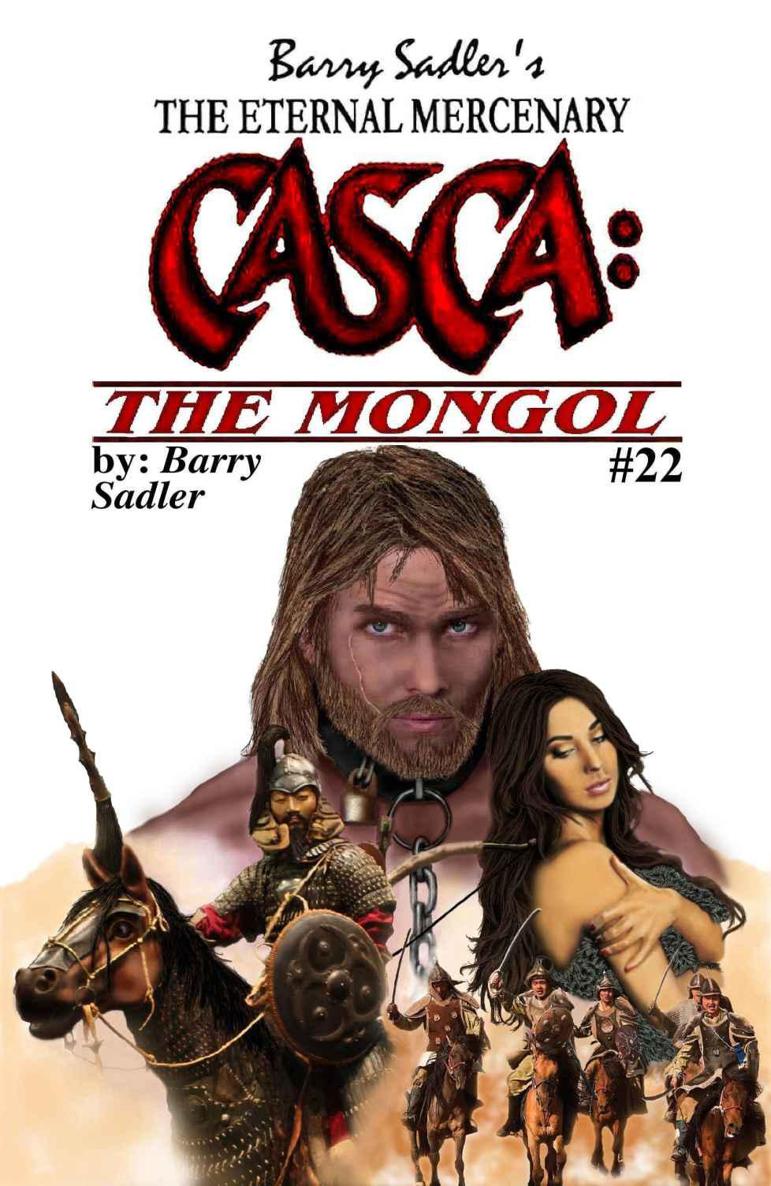

Casca 22: The Mongol

Read Casca 22: The Mongol Online

Authors: Barry Sadler

This is a book of fiction. All the names, characters and events portrayed in this book are Fictional and any resemblance to real people and incidents are purely coincidental.

CASCA: #22 The Mongol

Casca Ebooks are published by arrangement with the copyright holder

Copyright © 1990 by Barry Sadler

Cover: Greg Brantley

All Rights Reserved

Casca eBooks are for personal use of the original buyer only. All Casca eBooks are exclusive property of the publisher and/or the authors and are protected by copyright and other intellectual property laws. You may not modify, transmit, publish, participate in the transfer or sale of, reproduce, create derivative works from, distribute, perform, display, or in any way exploit, any of the content of our eBooks, in whole or in part. eBooks are NOT returnable.

The first rank of Temujin's warriors stepped to the rear three paces. Each man had been standing in front of one of the hundreds of sharpened stakes that Casca had prepared for them. Their bodies concealed them from the view of the Kereit and Ong Khan.

The Kereit were too close to stop their charge, and the second wave behind them was at a full gallop. They had to go on to where those terrible pointed stakes the thicknesses of a man's arms were waiting to disembowel their horses.

The first wave rushed onto the stakes. The horses screamed and tried to shy away but couldn't. They were packed too close. The stakes reached deep into chests and shoulders of the horses, driving the animals insane with pain. Three hundred went down in the first rush, littering earth with kicking, jerking, bleeding bodies.

From high on the Altai came the desert winds that drove the whirling, flesh-devouring sands of the desert demon before them, shrieking as they raced across the barren steppes and into the wastes of Arabistan.

Zhoutai, hetman of the small band of nomadic Tatars who had taken shelter from the winds in a gorge protected on the north and south by a small range of mountains, wiped grit from his eyes with his smallest fingers, then replaced the rag covering back over his mouth and nose to keep from suffocating as the grains of sand tried to plug every pore and orifice of his less than sanitary body.

He had been through foul winds before – every year of his life. He could tell from the manner in which the winds screamed how long it would take before they would at last fade back to whatever hell they had come from.

This one still had one full night left in which to torture the earth and all it came in contact with. Then it, too, would fade, leaving the deserts and mountains strangely still and silent.

The silence, he knew, would not last long. Within a few days there would be a great gathering of voices as the tribes and clans of the end of the earth – the high steppes and deserts from Mongolia to the lands of the Rus – met on common ground. A common ground where tradition was the only law. One which would, for the time of the gathering, normally prevent those tribes and individuals with long-standing blood feuds or perhaps only a momentary fit of bad temper from killing each other. The traditions that would make them refrain from their normal bloody habits of cheerfully slaughtering each other for long enough to make wagers, race their horses and camels, and to trade for the things the others had not.

Manners would be at their best, each man careful not to offend or draw steel against another. For to do so would be the same as to commit suicide. As all the other tribes would immediately attack and kill the offending person in the most unpleasant manner available to them, and if the offending person's tribe attempted to come to his aid, then they, too, would be set upon and driven from the gathering forever. This custom insured good behavior for the four days of peace that came to the steppes once each year.

During this season's wagering, Zhoutai planned on making up for his losses of the past year when his favored horse had broken a leg during the bazhouki. Now he had a new animal – not a horse that is true, but he would pit it against the best of those ugly ones called Mongol. The animals the yellow people behind the Great Wall called the Hsuing Nu or Hsien Pei.

Turning his back to face away from the wind, he let it shove him forward half hunched over; his body was strange to Western eyes. His back was almost a hump, thick neck and shoulders resting on its oversize trunk. The legs were smaller and weaker than those of Western men. The bones had long since bowed out from the years of living in the saddle. The Tatar, as the Huns and Mongols, were men who lived in the saddle. Horsemen.

The earth was not their friend. If they could, they would have bred their sons while in the saddle and then had them suckled on mares’ milk and horse blood till they, too, could ride the winds.

Bending over, he opened the flap to the black felt tent, crawled inside the yurt, and sealed the skin doorway behind him. Zhoutai's eyes were little more than black slits set in deep folds of leathery skin, nearly sealed shut from the years spent staring across the open spaces and squinting to keep the eternal grains of sand from blinding him.

He focused on the beast where it was safely chained to a stout post driven deep into the earth. He made certain to keep it chained out of harm's way, so no harm would come to him. Already two of his men had been attacked when they had ventured too close to it. Both were strong fighting men with several kills to their credit and glory, but they, too, now made certain of each of the thick links of iron chain that secured the animal. One, Horjad, had his left arm nearly torn off at the socket, which meant that he was now almost useless and would live his days out as carrion dog fit only for the scraps of life tossed to him by an indifferent master. The other, Boddasi, was more fortunate. He had lost only his right ear and the thumb of the right hand where the beast had chewed it off before Zhoutai could whip the creature off him.

Zhoutai's two women huddled in their corner of the yurt, not looking at their master lest he wish something of them; the things he wished for usually caused pain to others. Their faces and eyes remained still as they worked lumps of rancid fat into their hair, working the greasy strands into thick braids which they then wrapped around their flattened foreheads.

Zhoutai removed his goatskin jacket, the one with the hair turned to the outside, scratched absently at an itinerant louse chewing away at his crotch, and lay down on a cushion of horsehair to eat: cold mutton and a piece of horseflesh from one of his animals, which had just rolled over on its side and died the day before, tongue hanging out of slavering jaws. The cause of death was unknown. The meat tasted as it should, even served more raw than cooked. This was washed down with kumass, the acrid brew of fermented mares’ milk.

Eyeing his beast, he thought the creature looked a bit under the weather. He needed for it to keep its strength up for the coming contests. Not out of charity – for there was none in his soul, if he had one – Zhoutai tossed the beast part of the lamb haunch he had been gnawing on.

Never did he smile at or acknowledge it. However many beatings he gave his animal, he was – as with his prize horses and stock – careful not to cripple it. After all, he had a solid investment in the animal, having paid hard shekels of Persian silver for it in the bazaar of Samarkand, where it had killed three opponents one after the other, and the last was killed as easily as the first.

Now the ugly creature would fight for him until it was either killed, or perhaps if offered enough, he would sell it. Take the money and leave these two worn-out things he had for women and go past the wall of Chin where the women were soft and the wine did not sour on the stomach.

His stomach, beneath his wrappings of hide and filth-soaked cloth of undetermined origin, gurgled in protest at the reception of Zhoutai's normal diet of soured mares’ milk and coarse meat. Rising, he moved grunting to the side of the tent nearest the women, where he pulled down his breeches and urinated with a strong yellow stream on the sand by their sleeping robes.

The beast chewed at the sinewy bone, tearing at the ligaments with strong yellow teeth, grunting in pleasure when it managed to separate a small piece of real flesh from the bone. It kept its eyes away from Zhoutai, afraid that he would lose his temper again and gain no more for his efforts than another lashing of the animal's already deeply scarred and mutilated hide.

Manacles and leg irons firmly attached to a stake the thickness of a large man's upper arms were driven deep into the hard-packed earth. To this the other end of his chains were firmly attached. The key to the locks he kept in a small bag of human skin hung on a leather thong around his neck.

Zhoutai knew without a doubt that if ever the stake or the chains came loose, the beast would be at him instantly, ripping his arms from his sockets or tearing out his throat with those strong yellow teeth that now worried at the bony shank with such determination.

He didn't look at Zhoutai, but he thought of the feel of the grime-encrusted neck between his fingers. The sweet sound of vertebrae being crushed as he applied all the force of his strong, knot-muscled body to the task. The pleasant task of manually tearing Zhoutai's head from its shoulders, thereby casting him out to whatever hell was best suited to accepting those of his ilk.

Casca had been a slave many times before and had fought for the pleasure of others more than once in the past. He had even performed in the great arenas of Rome. There he had killed before the eyes of the Imperial Caesar and won the rudis, the wooden sword of freedom, and been set free. Though not for long, before his mouth put him back into chains, this time on the oars of a galley plying the waters of the Mediterranean and the Aegean.

Slave he had been time and again, but the feel of chains upon his body was not that which he could easily accept. They ate at him as acid to his soul, wearing at him more each day. That acid of hate also tried day by day to dissolve whatever vestiges of humanity remained within him.

The bone was picked clean, as clean as the sands of the desert winds could have done. Before putting it aside, he cracked the bone between his teeth, sucking out the sweet marrow. Zhoutai winced at the sound and subconsciously moved his body a bit farther away from the beast, closer to the side of his tent. Putting the sucked-out bone aside, he also put away for the moment his thoughts. In spite of his hate, he knew he needed to rest. He would fight again soon.

Squirming his body around to where his chains caused him the least amount of discomfort, he closed his eyes, letting his black thoughts be drowned out by the screaming of the wind outside the yurt.

Before sleep claimed him, he reminded himself that he had time on his side, and time was the master of all. With it he had been slave and king and once even a god. Whatever he had to endure, he would. For he knew he could endure. That was his great secret. All others would come and go in one life span, but he would tarry.

Zhoutai had never spoken to his slave about his past life or where he had come from. One did not speak to property or animals. One worked them until they wore out or died. As with all his beasts, his concern for them was only with the immediate needs that would preserve their value to him.

The past of a slave – especially one such as this, who was obviously less than a real man, with his pale eyes and scarred flesh – meant nothing to him. His only value was in whether he could bring his master a profit. Which was as it should be, and natural with all beasts of burden.

Zhoutai had long ago lost any dreams he had held as a youth. They had faded with the realities of time and he was consumed by the hardness of life on the steppes, where tolerance, compassion, and any sign of weakness was an invitation for others to come and take from you that which you owned, and as often as not, that included your life.

The steppes, the mountains, and the deserts were all unforgiving, merciless. They did not think or feel. They were only what they were, and that was natural. All other notions were artificial and would destroy you if you listened to them. Perhaps in other lands they could afford this luxury of sentiment, but not here. Here, there was only power in all its ten thousand degrees and variations. The power of nature and the power of man over his own kind.

Zhoutai was not the only one who thought this way. The Hsuing Nu, Hsien Pei, White Huns, Tatars, Turkomen, and Uighar all knew this was the way of their lives. Their only way.

It once had led one of them to greatness over the softer lands of the West and the rich lands of Persia. One of them had taken the sword and gone to the gates of Rome itself. The Lord Attila.

Once, as a child, Zhoutai had a fleeting dream he now no longer recalled. A dream of being the next Attila. Of uniting all the tribes of the East under his standard, and driving to the West, even over the Great Wall, into the soft belly of Chin.

But the dream had died stillborn, and no one else had come forth to bind the thousand tribes together. No one strong enough or wise enough to deal with the blood feuds and hatred between them. No one who could force them to one will and lead them to glory and power over their enemies. Never would there be another one who could walk in the shadow of the Lord Attila – never.

The dream had died within Zhoutai, and he was what he was. Alone, bitter and cruel as his life had made him.