Cascadia's Fault (26 page)

Authors: Jerry Thompson

Because the Okushiri waves struck in darkness there were few eyewitnesses as the tsunami approached. This animation was apparently the only way to know how the shape of the local sea floor had affected the incoming water. Case histories elsewhere explained and verified what the computer was showing.

“There are eyewitness accounts from the Chile event that sounded really weird,” Titov offered. “They were saying the second wave was sitting outsideâoffshoreâwaiting and gaining force . . . And that's what it was,” he pointed again at the screen. “That was this hydraulic troughânot propagating any more, just sitting there . . . The second wave competing with the retreat from the first wave, creating a standing wave pattern.”

The point of showing us the playback of the Okushiri tsunami was to illustrate how far wave modeling had come by 1993. “This was in fact the first wave that we've tested our model against in terms of real event simulations,” said Titov. “It was the most studied and the largest event before Sumatra, really.” The model was still a prototype, however, and much work remained to be done. New research programs were launched to figure out how to simulate the small-scale details of coastal terrain and more complex problems such as the way waves break, how

they transport sediment and debris, and how a wall of moving water interacts with solid objects on land.

they transport sediment and debris, and how a wall of moving water interacts with solid objects on land.

The lessons of Okushiri were encouraging for Vasily Titov and his colleagues. “You really wonder what's behind it,” he mused, “what kind of wonders mathematics can do. Writing equations, putting it in the computer, plotting it. And then you see the wave evolving just like you saw on TV . . . Things that I saw when I did the animation of the tsunami in Japanâwe would never see it just looking at the formulas . . . It's really the power of mathematics working for you.”

As the research began to accelerate, so did the ramifications of ignoring or neglecting Cascadia as a major public-safety issue. Within months of the Okushiri disaster in Japan, another scare in the Pacific Northwest and sobering new science from Canada would force politicians to take the initial concrete steps toward a viable coastal warning system. Festering debates and old controversies would be put to rest as the scale and potential of Cascadia's fault became glaringly undeniable.

Â

In San Francisco, on Market Street near the Ferry building, the ground beneath the street collapsed. This photo was taken on April 20, 1906, two days after the quake. (

U. S. Geological Survey

)

U. S. Geological Survey

)

Â

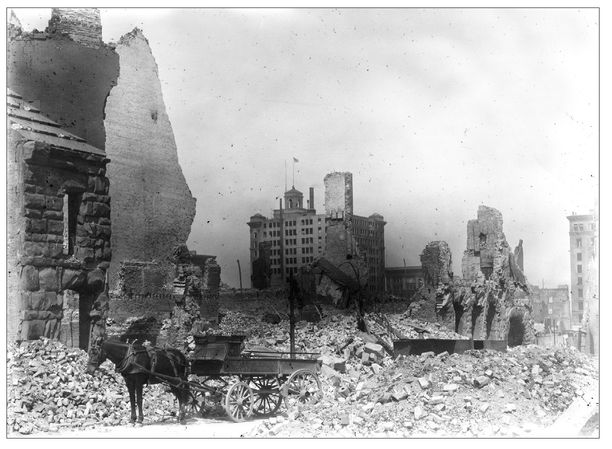

A scene of near-total destruction in downtown San Francisco on May 7, 1906. The outer framework of the California Hotel (center) survived the quake, while all around it was rubble and ruin. (

U.S. Geological Survey

)

U.S. Geological Survey

)

Â

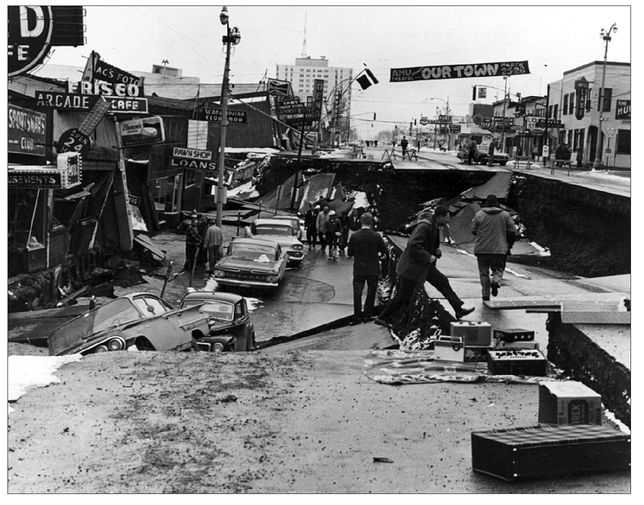

A scene from the Alaska earthquake of March 27, 1964. Fourth Avenue in Anchorage collapsed when the ground subsided eleven feet (3.3 m) vertically and lurched fourteen feet (4.3 m) horizontally at the same time.

(

U.S. Geological Survey

)

U.S. Geological Survey

)

Â

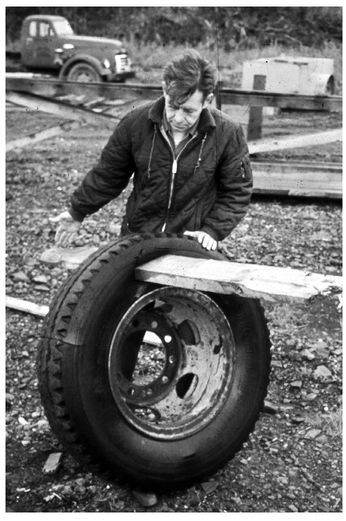

A man examines a ten-ply tire through which a plank of wood has been driven by a waveâan indication of the violent force of the tsunami surge that struck Whittier, Alaska, on March 27, 1964. (

U.S. Geological Survey

)

U.S. Geological Survey

)

Â

This photograph, taken in Port Alberni, British Columbia, on March 28, 1964, shows the aftermath of the Alaska earthquake and tsunami. Two of six waves that travelled more than 1,800 miles (3,000 km) from the Gulf of Alaska roared up the Alberni Inlet, flipping cars, smashing fifty-eight homes, and damaging 375 others. (

Alberni Valley Museum Photograph Collection, PN13805/Charles Tebby

)

Alberni Valley Museum Photograph Collection, PN13805/Charles Tebby

)

Â

The Alaska tsunami of 1964 also hit Crescent City, California, where more than a dozen people died when they ventured back into the danger zone after the first wave, thinking the worst was over. Four of the six huge waves generated in Alaska struck the California coast with deadly effect. (

Del Norte County Historical Society

)

Del Norte County Historical Society

)

Â

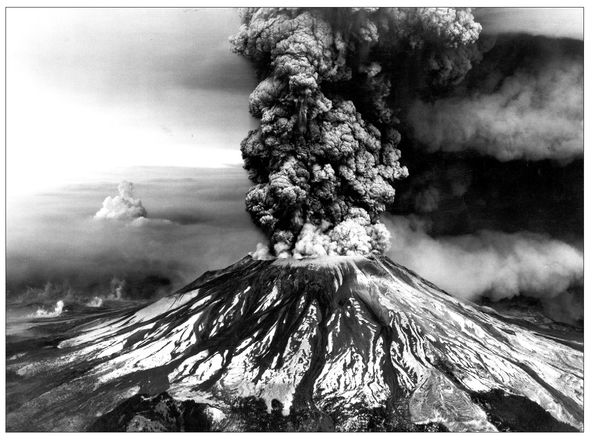

An aerial view of the eruption of Mount St. Helens, Washington, near the Oregon border, on May 18, 1980. This photo shows physical evidence of a tectonic plate being shoved beneath North America along the Cascadia Subduction Zone. (

U.S. Geological Survey

)

U.S. Geological Survey

)

Â

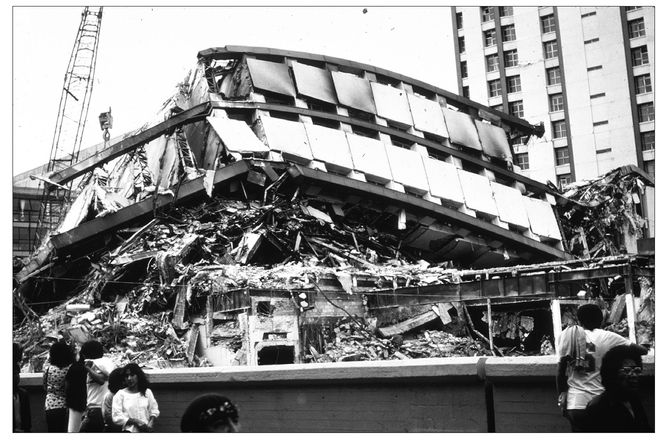

Earthquake energy traveled long distance from the West Coast to Mexico City on September 19, 1985, with devastating effects on high-rise buildings, which vibrated in harmonic resonance with the low-frequency shockwaves. (

U.S. Geological Survey

)

U.S. Geological Survey

)

Â

Paleoseismologist Brian Atwater discovered this ghost forest on the Copalis River in Washington State in March 1986. The trees and other freshwater plants were killed by salt water when coastal lowlands dropped below high-tide level, probably during Cascadia's last megathrust earthquake on January 26, 1700. (

U.S. Geological Survey/Brian Atwater

)

U.S. Geological Survey/Brian Atwater

)

Â

The Loma Prieta (or World Series) earthquake of October 17, 1989, caused deadly destruction in the San Francisco Bay Area. This photograph shows the support columns that failed, causing the collapse of the Cypress Viaduct (Interstate 880) in Oakland. (

U.S. Geological Survey

)

U.S. Geological Survey

)

Other books

Clouds In My Coffee by Andrea Smith

My Hope Next Door by Tammy L. Gray

Stray Cat Strut by Shelley Munro

Pop Tarts: Omnibus Edition by Brian Lovestar

Ollie, Ollie Hex 'n Free by Liz Schulte

Everything Beautiful Began After by Simon Van Booy

A Series of Murders by Simon Brett

Nosferatu the Vampyre by Paul Monette

Damned If You Do by Marie Sexton

Outsider by W. Freedreamer Tinkanesh