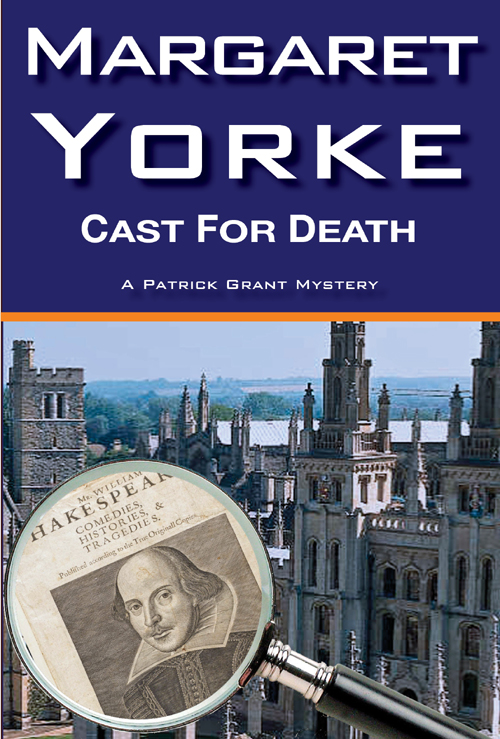

Cast For Death

Cast For Death

First published in 1976

© Margaret Yorke; House of Stratus 1976-2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The right of Margaret Yorke to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

This edition published in 2012 by House of Stratus, an imprint of

Stratus Books Ltd., Lisandra House, Fore Street, Looe,

Cornwall, PL13 1AD, UK.

Typeset by House of Stratus.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress.

| | EAN | | ISBN | | Edition | |

| | 0755130111 | | 9780755130115 | | Print | |

| | 0755134672 | | 9780755134670 | | Kindle | |

| | 0755134788 | | 9780755134786 | | Epub | |

This is a fictional work and all characters are drawn from the author’s imagination.

Any resemblance or similarities to persons either living or dead are entirely coincidental.

Born in Surrey, England, to John and Alison Larminie in 1924, Margaret Yorke (Margaret Beda Nicholson) grew up in Dublin before moving back to England in 1937, where the family settled in Hampshire, although she now lives in a small village in Buckinghamshire.

During World War II she saw service in the Women’s Royal Naval Service as a driver. In 1945, she married, but it was only to last some ten years, although there were two children; a son and daughter. Her childhood interest in literature was re-enforced by five years living close to Stratford-upon-Avon and she also worked variously as a bookseller and as a librarian in two Oxford Colleges, being the first woman ever to work in that of Christ Church.

She is widely travelled and has a particular interest in both Greece and Russia.

Margaret Yorke’s first novel was published in 1957, but it was not until 1970 that she turned her hand to crime writing. There followed a series of five novels featuring

Dr. Patrick Grant

, an Oxford don and amateur sleuth, who shares her own love of Shakespeare. More crime and mystery was to follow, and she has written some forty three books in all, but the Grant novels were limited to five as, in her own words, ‘authors using a series detective are trapped by their series. It stops some of them from expanding as writers’.

She is proud of the fact that many of her novels are essentially about ordinary people who find themselves in extraordinary situations which may threatening, or simply horrific. It is this facet of her writing that ensures a loyal following amongst readers who inevitably identify with some of the characters and recognise conflicts that may occur in everyday life. Indeed, she states that characters are far more important to her than intricate plots and that when writing ‘I don’t manipulate the characters, they manipulate me’.

Critics have noted that she has a ‘marvellous use of language’ and she has frequently been cited as an equal to P.D. James and Ruth Rendell. She is a past chairman of the Crime Writers’ Association and in 1999 was awarded the

Cartier Diamond Dagger

, having already been honoured with the

Martin Beck Award

from the Swedish Academy of Detection.

I should like to thank the Marquis of Tavistock for his help and advice, and for consenting to appear in these pages. Every other character, and all the events, are imaginary. My thanks are due, also, to Bill Allan for taking me behind the scenes at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, and to James Fehr for arranging a concert for me and answering questions about facilities at the Queen Elizabeth Hall.

M.Y.

Margaret Yorke began her writing career with what she later described as ‘family problem’ novels. After writing several in that genre she realised that she was constantly forcing herself to resist the temptation to stir up their quiet plots with some violent action. In 1970 she gave way and turned at last to crime fiction, beginning with a whodunnit because the pattern for them had been established by other successful women writers such as Dorothy L. Sayers and Agatha Christie. Margaret Yorke’s detective, Patrick Grant, was an Oxford don, and following a tradition set by Lord Peter Wimsey and Ngaio Marsh’s Rory Alleyn, he was handsome, a little absent minded, and had a habit of quoting Shakespeare.

Patrick Grant’s first appearance was in

Dead in the Morning

and his fifth, and last, came in

Cast For Death

which was published in 1976.

It is a book with a tightly dovetailed, complicated plot and a cast of interesting people. Although this is not a back-stage novel about the theatre, performances of Shakespeare’s plays in London and Stratford-upon-Avon are an important strand in the story. For Margaret Yorke herself admits ‘I’m nutty about Shakespeare and mad about Macbeth.’

The action includes a performance of

Othello,

with whose theme the novel’s reader is bound to draw parallels. ‘Slowly the lights dimmed. Liz and Patrick forgot about . . . everything as Roderigo and Iago entered, and before them began the build-up of circumstantial evidence that would end, some three hours later, in tragedy.’

Cast for Death

was not intended to be a tragedy but, like other classical detective stories, was written to provide its readers with an intellectual entertainment. As such, it is absorbing and highly enjoyable. But much as she revelled in devising puzzles for Patrick Grant to solve, Margaret Yorke has always been more interested in people than plots. Once established as a crime writer she found herself turning to novels of psychological suspense. The first of them was about a retired army officer who got involved in the death of a girl from his village quite by chance. His life was ruined by the neighbours’ gossip and eventually he blew his brains out. Margaret Yorke explained how the idea for

No Medals for The Major

came to her. It was ‘when I was thinking about how different we often feel inside from the face we present to the world, and how an action, slight in itself, can have profound effects on other people whom we may never meet.’

Twenty years on from the publication of

Cast for Death,

Margaret Yorke has become widely popular and well known as the author of subtle novels about people who are the victims of events. Many of them include young people who have drifted into delinquency and crime. She does not restrict herself to writing about any particular class, but portrays a cross section of the population, always demonstrating the psychological insight which was already such a strong feature in

Cast For Death.

Nearly all her books are set in an English village or small town, in whose existence we entirely believe because the author is writing about a world she knows intimately herself. Living in a cottage in a village street, Margaret Yorke is well aware it is not the artificial and idealised environment of pre-war crime novels. And she is careful to write about what she knows or to do research when she needs to; she even makes a point of regular updates on police procedure from her neighbourhood police officers.

Patrick Grant’s life as a don was familiar to his creator too, for she has worked as a librarian at an Oxford college; the places where his adventures were set, such as Greece, she knew from foreign holidays.

There is, in fact, an authority in crime novels by Margaret Yorke which allows their readers to believe in the ordinary people who have been impelled into action because their ordinary lives have accidentally caught them up in extraordinary events. The underlying theme of all Margaret Yorke’s work is expressed in a quotation of a saying by the eighteenth century statesman Edmund Burke at the end of

Cast For Death.

‘All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.’

JESSICA MANN

1

The body lay just beneath the surface of the river, the hair streaming in the tide, legs splayed with the movement of the water, arms spread, the face downwards. Above, unaware of what floated so obscenely close to them, people surged along the terraces outside the concert halls, and theatregoers crossed to the parking lots beside the Festival Hall, their voices and the sound of car engines noisy in the air.

Against the clear night sky, London’s great buildings stood out, etched in brilliant detail. Dr Patrick Grant, Fellow of St Mark’s College, Oxford, leaned against the parapet overlooking the Thames and approved of what he saw. The river flowed darkly past, a jet mirror studded with the silver reflections of the lights on each bank; he stared across the water, and turned over in his mind the problem of where to eat. The evening had not gone as planned; he had intended to spend it with Liz Morris, whom he had known since his own undergraduate days, but when he reached the Fantasy Theatre where they were to have seen

Macbeth

together, he found not Liz, but a message to say she could not come. No reason was given. It was too late to find another companion, so he had turned in the second ticket; it had been sold to a large man in a corduroy jacket who had flowed across the seat-arm between them and had eaten toffees throughout the performance.

And Sam Irwin had been out of the play. It was to see him, as well as the much-lauded Macbeth of Joss Ruxton, that Patrick had come up to London. He had enjoyed the play, whenever his restless neighbour stopped fidgeting, for the verse was well spoken and the director had allowed the words and the action to exert their own power over the audience without extravagant distractions of his own. But a programme note said that Sam Irwin was indisposed, and Macduff was played by someone unknown. The play was at the end of its run in a season which was to conclude with

Henry VIII,

so there would be no other chance to see Sam in the part.

Patrick had planned to invite the actor, whom he and Liz had first met in Austria four years before, to eat with them afterwards; now, it seemed pointless to go alone to an expensive restaurant, though he must have some sort of meal before returning to Oxford.

At this point in his reflections he saw it: something white in the river not far away. Patrick’s attention concentrated on the spot where the object had broken the surface of the water a short distance upstream. There it was again, and now he identified it: it was a hand, white and ghostly, the fingers gently curled as the water parted over it and left it exposed. He stared in horror: this was no mystic, legendary arm offering a sword: this was grim death.