Catastrophe: An Investigation Into the Origins of the Modern World (30 page)

Read Catastrophe: An Investigation Into the Origins of the Modern World Online

Authors: David Keys

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #Geology, #Geopolitics, #European History, #Science, #World History, #Retail, #Amazon.com, #History

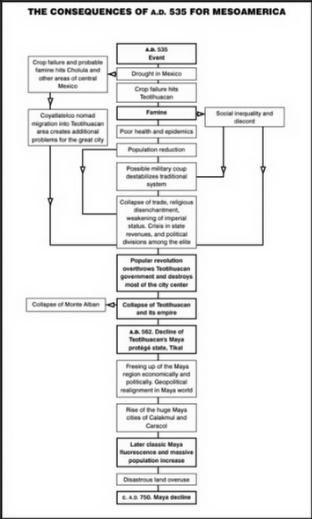

The religious dimension in the gathering catastrophe was almost certainly of prime importance. As already outlined, the major deities—Tlaloc, the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl, and the Mother of Stone—were all associated, to one extent or another, with rain. So when the rains failed and continued to fail dramatically, probably for several decades with little respite, there was almost inevitably a crisis in religious confidence. It is very likely that the water mountain representing the Mother of Stone herself would have dried up and stopped gurgling.

Rain underpinned not only the city’s agricultural and religious systems but also, indirectly, the system of political control itself. Government was seen as having divine origins. The rulers of Teotihuacan certainly governed with divine sanction and possibly even as representatives of the gods—perhaps even as deities, or incarnations of deities, themselves. Certainly Quetzalcoatl was a god associated with the institution of rulership, and the cream of the city’s elite are thought to have actually lived within the complex of palaces and other structures built around the great Temple of Quetzalcoatl.

Teotihuacan, as the religious heart of the Mesoamerican cosmos, was almost certainly a sort of theocratic state in which religion, nurtured by the life-giving divine gift of rain, played an overwhelmingly important role. And so it is easy to see how persistent drought led—through agricultural failure, famine, and disease—to religious and therefore political disillusionment.

A

s disaster unfolded in the metropolis, the empire began to unravel—the weakened center was disintegrating, and the mainstay (and raison d’être) of empire, trade, was also disintegrating. Evidence from another major central Mexican site, Cholula, suggests that it (and presumably many other centers) were equally badly hit by the drought. Famine-induced population reductions and increased poverty throughout much of Mexico would have drastically reduced trade levels. What commerce was left would no doubt have been further restricted by increased social disorder, population movement, and banditry.

The obsidian industry—and probably several others—were under some form of Teotihuacano state control, and the reduction in trade must have robbed the government of revenues and power. Archaeological evidence from all over Mesoamerica shows Teotihuacano trade and influence shrinking in the latter half of the sixth century.

The end of the Mesoamerican Jerusalem and its empire was now fast approaching. Only one final and violent act remained to be played out—for all the archaeological evidence indicates that the lights finally went out in Teotihuacan in a veritable orgy of flames and bloody murder.

The selective way in which the destruction was carried out and the obviously emotional zeal with which individual members of the elite were slaughtered strongly suggests that the forces that ended Teotihuacano civilization were internal, not external.

During what appears to have been an extraordinarily violent popular insurrection nearly every major building in the city associated with the ruling elite was ransacked, torn apart, and put to the torch.

13

In the city center, archaeological excavations have yielded evidence that between 147 and 178 palaces and temples were burned to the ground in an orgy of systematic, hate-filled destruction, quite possibly of an intensity without parallel in human history. In the rest of the metropolis between 50 and 60 percent of the temples were torched. Religious buildings (and the palaces in the city center) were the main targets. Relatively few apartment compounds were attacked, and those that were probably belonged to extended families that were somehow associated with the government or with the failed religious system.

Thousands of angry citizens must have surged into the city center and broken into the main palace complex, where they would have come face-to-face with those members of Teotihuacan’s elite who had not already fled—and who now stood no chance at all. Still wearing their jade, obsidian, and onyx mosaic crowns bedecked with iridescent blue and green feathers, many were cut down with the utmost barbarity. Archaeological detective work has revealed how one nobleman or priest was seized in the west room of the Ciudadela Palace’s northwest apartment and dragged some distance into the complex’s central patio, where most of his body was left. His skull had been shattered and his body hacked to pieces, bits being scattered on the ground all the way from the west room to the patio. The archaeological investigation revealed that he was a very high-status individual. Pieces of a jade mosaic (probably from a headdress) and jade, onyx, and shell beads (probably from a necklace) were found around his shattered corpse.

14

Another similarly dismembered victim was found nearby, and a third was in the south palace. The small number of skeletons discovered so far suggests either that much of the elite had succeeded in escaping in the days immediately before the insurrection, or that they had been seized by rebels and murdered elsewhere.

After hunting down and killing the last remaining members of the ruling elite, the mob set about the systematic destruction of the politico-religious heart of the city. The presumably wooden (and perhaps textile) constructions at the bottom and sides of temple platform staircases, and the partly wooden temples themselves, were set afire. Archaeological excavations have revealed evidence of intensely destructive burning in these particular locations in most temple complexes.

In the temple in the Ciudadela Palace complex, a structure closely associated with traditional government, archaeologists discovered that five statues had been deliberately removed from the sacred area and smashed. Dozens of fragments were then equally deliberately thrown in every conceivable direction. The shattered remnants of one of the figures—a two-foot-high statue of a goddess—were found scattered over nearly a thousand-square-foot area!

In the same governmental complex, at the spectacular seven-tiered pyramid temple of Quetzalcoatl, sacred sculpted stone heads were hurled down into adjacent passageways and even into the patios of one of the neighboring palaces. In the palaces themselves, six smashed images of the discredited and now presumably hated rain god, Tlaloc, were found among the ash and the debris.

The rebels had systematically torn apart and shattered the objects of their anger. The depths of vengeful hatred that must have driven this wave of destruction can hardly be imagined, but must have reflected the sufferings endured prior to the revolt by the mass of Teotihuacan’s population.

As the flames consumed one part of the city center, angry mobs surged into other central areas. At the pyramid temple of the Mother of Stone (now known as the Pyramid of the Moon) the huge stone blocks that flanked a great staircase adjacent to the pyramid were hurled down and ended up a hundred yards away. The homes of priests or nobles associated with the temple were ransacked. Twelve massive carved pillars, adorned with military insignia, were pulled over.

And at a temple in another part of the city—in the Puma Mural group of buildings—archaeologists again found evidence that stone blocks had been deliberately removed and tossed down into a plaza. The force of each impact was so great that the blocks literally bounced across the surface of the square, leaving a trail of telltale impact marks. There too a sacred statue—a valuable green onyx figure of a god—had been violently smashed. The temple was then torched; 1,500 years later, archaeologists even found where the burning beams had fallen.

As Teotihuacan destroyed itself—or in the run-up to the final crisis—a huge 200-ton statue, probably depicting the god Tlaloc, was being carved—perhaps on the orders of the doomed Teotihuacano government and priesthood—far away from the metropolis, on the slopes of a sacred mountain

15

associated with the god. The statue, one of the largest in the world and certainly the largest ever made in Mesoamerica, seems to have symbolized the religious conflict that must have raged as the Teotihuacan endgame unfolded. Traditional Tlaloc loyalists—the government and members of the ruling class—may well have ordered the creation of this unprecedentedly huge idol in a last, desperate bid to persuade the god to produce rain.

16

But the rains didn’t come, insurrection broke out, the Mesoamerican Jerusalem destroyed itself, and Tlaloc’s two-hundred-ton bulk was abandoned for one and a half millennia on the slopes of his own holy mountain—a fitting symbol for the end of the greatest civilization ever to have flourished in the ancient New World.

T H E D A R T S O F

V E N U S

S

ometime in late 561 or early 562, the enemies of one of Mesoamerica’s greatest cities, Tikal, began to plan to destroy its power.

To bring down Tikal, a city of some thirty thousand people, would require nothing less than the fiercest form of conflict known to the Maya, namely, cosmic war. It was the job of the priests, with their deep astronomical knowledge, to enlist the support of an appropriate divine cosmic body. So in late 561 or early 562, the priests of Tikal’s great rival, the city of Calakmul, recruited no less an ally than Venus himself.

For the Maya, Venus was no Old World goddess of love, but a very male god of war and disaster. They were confident that he would rain down cosmic darts and destruction on their Tikali enemies. But to ensure the deity’s support, Venus had to be in precisely the right place at the right time so that he might strike down the enemy and guarantee victory.

The Calakmul soldiers would simply be the instruments of the god—not independent human beings dependent on chance, but warriors implementing a divinely ordained destiny. For fate to smile on Calakmul’s cosmic plan, just one human choice had to be made absolutely correctly: the selection of the day for the attack. It had to be one that would enable Venus to strike with all his power, and so the Calakmul priests chose 29 April 562—the only day in the planet’s eighteen-month cycle on which it actually appeared to stand stock-still, ready to pounce.

And so it was that Calakmul and its allies attacked and humbled the great city of Tikal. Backed by his divine Venusian war patron, the ruler of Calakmul—the appropriately named King Sky Witness—took control and appears to have installed as the city’s ruler a puppet king, a young boy called Animal Skull, who could not have been much more than nine years of age at the time.¹

For the Tikal elite, the aftermath of conquest was a time of ignominy and bloodstained suffering. The attack had almost certainly not been a purely external event. A fifth column of disgruntled members of the ruling family probably collaborated with the conquest of their city, and it is likely that Animal Skull was the son of one of the members of this alienated group. Indeed, it was probably this fifth column that was responsible for deliberately and very selectively smashing up the intricately carved royal commemorative monuments in the city’s great plaza. The four previous monarchs who had ruled successively from 511 until the 562 conquest appear to have been absolutely loathed by the incoming Animal Skull regime, for it was their monuments that were selected for destruction. Their two predecessors’ monuments (covering the period 458 to 511) were ostentatiously left untouched.

A disproportionate share of this dynastic hate seems to have been reserved for the first of the post-511 rulers—a woman known to Mayanists as the Lady of Tikal. Female succession was very rare in the Maya world, and it has to be assumed that her accession was the result of a major political crisis—perhaps a sort of coup d’etat in which powerful nonroyal figures sought to gain power by placing her on the throne.

It seems likely that the change of regime in 562 was the violent denouement of a dynastic sequence of events that had started in 511 with the presumably irregular accession of the Lady of Tikal. The splendidly ignominious aspect of this pivotal year would have been symbolized by the enthronement of the boy king. A powerless puppet in the hands of Calakmul, his accession nevertheless would have been typically flamboyant.

A jade mask would have partly obscured his face, while an intricate wood and jade headdress composed of further mask images and topped with rare green quetzal feathers would have towered above his head. Large jade pendants decorated with intricate floral designs would have hung heavily from his ears, while lying across his bare chest would have been a ten-inch-long rectangular jade ceremonial plaque. Attached to an intricate belt would have been three jade skull masks. And around his middle, above his loincloth, he probably sported a jaguar-pelt skirt, open at the front, while his royal feet would have been clad in leather sandals decorated with small masks and feathers.