Century of the Soldier: The Collected Monarchies of God (Volume Two) (2 page)

Read Century of the Soldier: The Collected Monarchies of God (Volume Two) Online

Authors: Paul Kearney

Tags: #Fantasy

A huge paw, fingered and taloned like some mockery of man and beast, raised him to his knees. Its pads scorched his skin through the wool of his winter shift.

The face of the winter's wolf, its ears like horns above a massive black-furred skull in which the eyes glared like saffron lamps, black-slitted. A foot-long fanged muzzle from which the saliva dripped in silver strings, the black lips drawn back taut and quivering. And caught in the teeth, some glistening vermilion gobbet.

Eat.

Himerius was weeping, terror flooding his mind. "Please master," he blubbered. "I am not ready. I am not worthy -"

Eat.

The paws clamped on to his biceps and he was lifted off his feet. The bed creaked under them. His face was drawn close to the hot jaws, its breath sickening him, like the wet heat of a jungle heavy with putrefaction. A gateway to a different and unholy world.

He took the gobbet of meat in his mouth, his lips bruised in a ghastly kiss against the fangs of the wolf. Chewed, swallowed. Fought the instinct to retch as it slid down his gullet as though seeking the blood-dark path to his heart.

Good. Very good. And now for the other.

"No, I beg you!" Himerius wept.

He was thrown to his stomach on the bed and his shift was ripped from his back with a negligent wave of the thing's paw. Then the wolf was atop him, the awesome weight of it pinioning him, driving the air out of his lungs. He felt he was being suffocated, could not even cry out.

I am a man of God. Oh Lord, help me in my torment!

And then the sudden, screaming pain as it mounted him, pushing brutally into his body with a single, rending thrust.

His mind went white and blank with the agony. The beast was panting in his ear, its mouth dripping to scald his neck. The claws scored his shoulders as it violated him and its fur was like the jab of a million needles against his spine.

The beast shuddered into him, some deep snarl of release rising from its throat. The powerful haunches lifted from his buttocks. It withdrew.

You are truly one of us now. I have given you a precious gift, Himerius. We are brethren under the light of the moon.

He felt that he had been torn apart. He could not even lift his head. There were no prayers now, nothing to plead to. Something precious had been wrenched out of his soul, and a foulness bedded there in its place.

The wolf was fading, its stink leaving the room. Himerius was weeping bitterly into the mattress, blood trickling down his legs.

"Master," he said. "Thank you, master."

And when he raised his head at last he was alone on the great bed, his chamber empty, and the wind picking up to a howl around the deserted cloisters outside.

Part One

M

IDWINTER

The spirit which knows not how to submit,

which retires from no danger because it is formidable,

is the soul of a soldier.

- Robert Jackson,

A Systematic View on the Formation,

Discipline and Economy of Armies

, 1804

One

N

OTHING

I

SOLLA HAD

been told could have prepared her for it. There had been wild rumours, of course, macabre tales of destruction and slaughter. But the scale of the thing still took her by surprise.

She stood on the leeward side of the carrack's quarterdeck, her ladies-in-waiting silent as owls by her side. They had a steady north-wester on the larboard quarter and the ship was plunging along before it like a stag fleeing the hounds, sending a ten-foot bow-wave off to leeward which the weak winter sunlight filled full of rainbows.

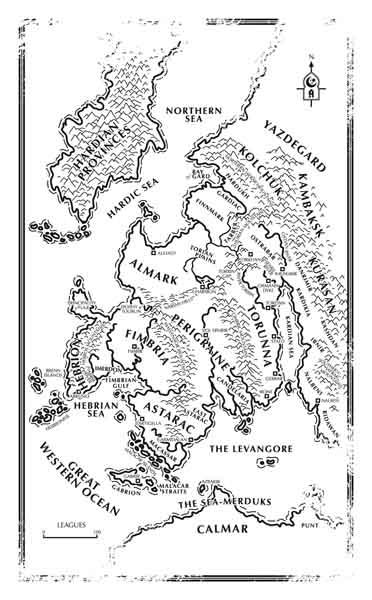

She had felt not a smidgen of sickness, which pleased her; it was a long time since she had last been at sea, a long time since she had been anywhere. The breakneck passage of the Fimbrian Gulf had been exhilarating after the sombre gloom of a winter court, a court which had only recently emerged from an attempted coup. Her brother, the King of Astarac, had fought and won half a dozen small battles to keep his throne. But that was nothing compared to what had gone on in the kingdom that was her destination. Nothing at all.

They were sailing steadily up a huge bay, at the end of which the capital of Hebrion, gaudy old Abrusio, squatted like a harlot on a chamberpot. It had been the rowdiest, most raucous, godless port of the western world. And the richest. But now it was a blackened shell.

Civil war had scorched the guts out of Abrusio. For fully three miles, the waterfront was a smoking ruin. The hulks of once-great ships jutted out of the water along the remnants of the wharves and docks, and extending from the shore was a wasteland hundreds of acres in extent. The still-smoking wreck of the lower city, its buildings flattened by the inferno which had raged through it. Only Admiral's Tower stood mostly intact, a gaunt sentinel, a gravestone.

There was a powerful fleet anchored in the Outer Roads. Hebrion's navy, depleted by the fierce fighting to retake the city from the Knights Militant and the traitors who had been in league with them, was a force to be reckoned with, even now: tall ships whose yards were a cat's cradle of rigging lines and furiously busy mariners, repairing the damage of war. Abrusio still had teeth in plenty.

Up on the hill above the harbour the Royal palace and the monastery of the Inceptines still stood, though pitted by the naval bombardment which had ended the final assaults. Up there, somewhere, a king awaited them, looking down on the ruins of his capital.

I

SOLLA WAS SISTER

to a different king. A tall, thin, plain woman with a long nose that seemed to overhang her mouth except when she smiled. A cleft chin, and a large, pale forehead dusted with freckles. She had long ago given up trying for the porcelain purity that was expected of a courtly lady, and had even put aside her powders and creams. And the ideas which had prompted her to don them in the first place.

She was sailing to Hebrion to be married.

Hard to remember the boy who had been Abeleyn, the boy now become a man and a king. In the times they had seen each other as children he had been cruel to her, mocking her ugliness, pulling at the flaming russet hair that was her only glory. But there had been a light about him, even then, something that made it hard to hate him, easy to like. "Issy Long-nose," he had called her as a boy, and she had hated him for it. And yet when the young Prince Lofantyr had tripped her up in the mud one winter's evening in Vol Ephrir, he had ducked the future King of Torunna in a puddle and smeared the Royal nose in the filth Isolla stood covered in. Because she was Mark's sister, and Mark was his best friend, he had said. And he had wiped the tears from her eyes with gruff, boyish tenderness. She had worshipped him for it, only to hate him again a day later when she became the butt of his pranks once more.

He would be her husband very soon, the first man she would ever let into her bed. At twenty-seven she hardly worried about that side of things, though it would of course be her duty to produce a male heir, the quicker the better. A political marriage with no romance about it, only convenient practicalities. Her body was the treaty between two kingdoms, a symbol of their alliance. Outside that, it had no real worth at all.

"By the mark eleven!" the leadsman in the bows called. And then: "Sweet blood of God! Starboard, helmsman! There's a wreck in the fairway!"

The helmsmen swung the ship's wheel and the carrack turned smoothly. Sliding past the port bow the ship's company saw the grounded wreck of a warship, the tips of her yards jutting above the surface of the seas no more than a foot, the shadowed bulk of her hull clearly visible in the lucid water.

The entire ship's company had been staring at the war-wrecked remnants of the city. Many of the sailors were clambering up the shrouds like apes to get a better view. On the sterncastle the quartet of heavily armed Astaran knights had lost their impassive air and were gazing as fixedly as the rest.

"Abrusio, God help us!" the master said, moved beyond his accustomed taciturnity.

"The city is destroyed!" one of the men at the wheel burst out.

"Shut your mouth and keep your course. Leadsman! Sing out, there. Pack of witless idiots. You'd run her aground so you could gape at a dancing bear. Braces there! By God, are we to spill our wind with the very harbour in sight, and let Hebrians brand us for mooncalf fools?"

"There ain't no harbour left," one of the more laconic of the master's mates said, spitting over the leeward rail with a quick, hunted look of apology to Isolla a second later. "She's burned to the waterline, skipper. There's hardly a wharf left we could tie up to. We'll have to anchor in the Inner Roads and send in a longboat."

"Aye, well," the master muttered, his brow still dark. "Get tackles to the yardarms. It may be you're right."

"One moment, Captain," one of the knights who were Isolla's escort called out. "We don't yet know who is in charge in Abrusio. Perhaps the King could not retake the city. It may be in the hands of the Knights Militant."

"There's the Royal flammifer flying from the palace," the master's mate told him.

"Aye, but it's at half mast," someone added.

There was a pause after that. The crew looked to the master for orders. He opened his mouth, but just as he was about to speak the lookout hailed him.

"Deck there! I see a vessel putting off from the base of Admiral's Tower, and it's flying the Royal pennant."

At the same second the ship's company could see puffs of smoke exploding from the battered seawalls of the city, and a heartbeat later came the sound of the reports, distant staccato thunder.

"A Royal Salute," the leading knight said. His face had brightened considerably. "The Knights Militant and usurpers would never give us a salute - more likely a broadside. The city belongs to the Royalists. Captain, you'd best make ready to receive the Hebrian King's emissaries."

Tension had relaxed along the deck, and the sailors were chattering to each other. Isolla stood on in silence, and it was the observant master's mate who voiced her thought for her.

"Why's the banner at half mast is what I'd like to know. They only do that when a king is -"

His voice was drowned out by the pummelling of bare feet on the decks as the crew made ready to receive the Hebrian vessel that approached. As it came closer, a twenty-oared Royal barge with a scarlet canopy, Isolla saw that its crew were all dressed in black.

"T

HE LADY HAS

arrived, it would seem," General Mercado said.

He was standing with his hands behind his back, staring out and down upon the world from the King's balcony. The whole circuit of the ruined lower city was his to contemplate, as well as the great bays that made up Abrusio's harbours and the naval fortifications that peppered them.

"What the hell are we going to do, Golophin?"

There was a rustling in the gloom of the dimly lit room, where the light from the open balcony could not reach. A long shape detached itself soundlessly from the shadows and joined the general. It was leaner than a living man had a right to be, something crafted out of parchment and sticks and gnawed scraps of leather, hairless and bone-white. The long mantle it wore swamped it, but its eyes glittered brightly out of the ravaged face and when it spoke the voice was low and musical, one meant for laughter and song.