Challenger Deep (13 page)

Authors: Neal Shusterman

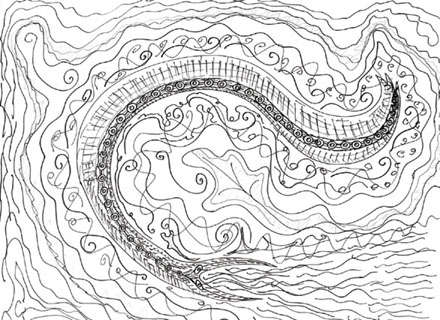

These mission meetings are always populated by the same crew members: me, the navigator, Bone-boy, the girl with the pearl choker, the blue-haired girl, and our pudgy lore-master. Each of us has struggled to excel at our assigned positions. The navigator and I have it easy—my drawings and his charts are treated as beyond scrutiny. The others, well, they fake their way through. Choker-girl, our dark and miserable morale officer, has learned to fake positive comments when under the captain’s glaring eye. The bone-boy reads whatever he thinks the captain wants to hear in the tossed bones, and the blue-haired girl claims she’s found everything from gold doubloons to crates of diamonds in the shredded manifests of sunken ships.

The lore-master, however, has a dangerous streak of honesty.

“I can’t do it,” he tells the captain at our group gathering. “I can’t make heads or tails of the runes in the book.”

The captain seems to swell like a sponge in water. “We care not of heads and tails, only of the flesh between!” Then the captain calls for Carlyle, who has been lurking in the corner, as he always lurks during these meetings. “Keelhaul him.”

The lore-master protests, beginning to hyperventilate at the

suggestion, then the parrot flaps out of nowhere to the captain’s shoulder.

“Clean the cannon!” the parrot says. “Have him clean the cannon!”

The captain swipes the bird off, dislodging several bright feathers, but the parrot is undeterred. “The cannon! The cannon!”

“Pard’n me, sir,” Carlyle says, “but maybe the bird is right. A keelhauling will leave him useless, if not dead. And the cannon needs a good cleaning if we’re to battle the beasts ahead.”

The captain’s eyeball fixes on Carlyle, burning at the insubordination—a lowly swabby second-guessing his order. But he holds his temper and waves his hand. “Do as you will,” he says. “As long as the boy suffers for his indolence.”

The parrot, now perched on a hanging lamp, looks at me and shakes his head sadly at the captain’s comment. I look away, not knowing what it means to be the focus of the parrot’s attention, and how the captain might react to it.

It takes Carlyle and two other brawny crewmen to drag the lore-master out, kicking and screaming at the prospect of the cannon, and I wonder why that would be as terrifying to him as a keelhauling. Once he’s gone, the captain returns to his agenda.

“Today is truly a momentous day,” the captain tells us, “for we shall test the diving bell and see if Caden’s knowledge of deep-sea exploration rings true.”

I feel queasy, and it has nothing to do with the motion of the ship. “But . . . it’s the wrong kind of bell,” I say, feeling small and impotent.

“You should have thought of that before you suggested it,” snarks the girl with blue hair.

“We’re all screwed,” says our morale officer.

It’s like this: You know the answers to everything. Your head is so full of answers, it’s bursting. It’s ready to explode and pour killing radiation on everyone. Your life will be declared a radioactive zone for hundreds of years if you can’t release some pressure by showing the truth of what you know to anyone who’ll listen. The lines, the

connections

you see between all things.

And you have to share it.

So you walk the streets, and spout out randomness at people, knowing there’s nothing random about it at all. People look at you strangely, and even in their gazes you can see the connections between you, them, and the rest of the world.

“I can see inside you,” you tell a woman carrying a bag out of the supermarket. “There’s a worm in your heart, but you can cast it out.”

She looks at you and then turns away, hurrying to her car, afraid of what you’ve told her. And you feel good. And not.

You feel pain down low, and you glance at your feet. You’re barefoot. You’ve been walking around that way, and it’s left your feet blistered, scraped, and bloody. You don’t remember taking off your shoes but you must have. There’s meaning to that, too.

Meaning to the way your flesh connects to the earth, telling gravity to hold you and everyone else down. And suddenly you know that if you put shoes on your feet, the world will let go and everyone will be hurled off into space, all because of a thin layer of rubber that would cut your connection to the ground.

You

are the antigravity lever of the world. As wonderful as knowing this is, the sheer awe of it is terrifying because of the power you have. And that worm you saw in the woman’s heart has somehow migrated into you. That’s not a heartbeat you’re feeling, it’s the worm eating its way through you and you can’t get it out.

Beside the supermarket is a travel agency fighting to stay alive in an age where travel is all booked online. You push your way through the door.

“Help me,” you say. “The worm. The worm. It knows what I know, and it wants to kill me.”

But a woman in a pantsuit roughly pushes you out the door, yelling at you. “Get away from here, or I’ll call the police.”

For some reason that makes you laugh, and your feet are bleeding, and that makes you laugh, too, and in the parking lot, a BMW sits with a broken headlamp, and that makes you cry. Leaning against the wall, you slide down in a heap and your soul fills with tears. You think of Jonah, who, after enduring being partially digested by the whale, burst into tears on a mountaintop when the gourd vine protecting him from the sun was devoured by a worm and died. The same worm. You understand his tears. How, with the sun beating down on his head, he was so grieved that he wanted to die.

“Please,” you say to anyone around you. “Please just make it stop. Please just make it stop.” Until someone from the Hallmark store, a woman much nicer than the travel witch, kneels down to you.

“Is there someone I can call?” she says kindly. But the thought of her calling your parents to come get you is enough to make you rise to your feet.

“No, I’m okay,” you tell her and you start moving away. You tell yourself you’ll be fine if you can find your way home. There is no whale to digest you here. The thing that’s eating you works from the inside out.

69. Your Meaning Is Irrelevant

Roll call. The sky is white, the distant horizon gray and sparking with faint lightning—not just ahead, but in all directions. The

captain paces the upper deck, looking down on the crew, going on about the great importance of the mission, and the importance of this particular day.

“Today Seaman Caden’s diving bell shall be put to the test, and the manner of our descent shall be once and for all determined.” He looks very authoritative—even more so now in his uniform of brass buttons and blue wool—but authority and reason are two different things.

“That’s not a bathyscaphe!” I call out. “It won’t work! That’s not what I meant by a diving bell!”

“Your meaning is irrelevant.”

It takes more than a dozen crewmen to lift the woefully miscast Liberty Bell to the railing. Then, on the captain’s order, the bell is hurled overboard. It sinks like a stone, and the rope—which has been gnawed upon by the feral brains—snaps, sending the bell to the irretrievable depths. A single bubble surfaces like a belch.

And the captain says, “Test successful!”

“What? How is that a successful test?” I shout.

The captain stalks toward me slowly, deliberately, his footsteps clicking on the copper-plated deck. “This test,” he says, “was to disprove your theory of how to achieve the bottom of the trench.” Then he shouts, “You were WRONG, boy! And the sooner you accept your complete and overwhelming wrongness, the sooner you’ll be of use to me, and this mission.” Then he storms away, very satisfied with himself.

It is only after the captain is gone that the parrot lands on my shoulder—something he rarely does—and says, “We need to talk.”

Your father stands in your path as you’re on the way out the door.

“Where are you going?”

“Out.”

“Again?” He’s much more forceful than the last time he asked, and he’s not moving out of your way. “Caden, your feet are full of blisters from all this walking.”

“So I’ll get better shoes.” You know he won’t understand why you have to walk. It’s this movement through the world that keeps you from blowing up. It keeps the world safe. It keeps the worm calm. Only it’s not a worm now. Today, it’s an octopus, with eyes instead of suction cups on its tentacles. It moves around inside you, inside your gut. Sliding around your organs, trying desperately to get comfortable. But you won’t tell your parents that. They’ll just tell you it’s gas.

“I’ll walk with you,” he says.

“No! Don’t do that. You can’t do that!” You push past him and out the door. You’re in the street. Today you have shoes and you realize now that wearing shoes won’t stop gravity from holding things to the earth. That was silly. How did you ever think that? But you do know that if you don’t walk, something terrible will happen somewhere and you’ll see it in the news tomorrow. You know that beyond a doubt.

Three blocks from home you look over your shoulder to see your father’s car slowly following you like a silver shark. Ha! And

they think

you’re

paranoid. There’s something very wrong with your parents if they have to follow you when you walk.

You pretend you don’t see the car. You just keep walking until long after dark. Not stopping, not talking to people. You let him follow you all the way around the neighborhood, then all the way home.

I awake to find the parrot watching me from the foot of my bed. I gasp. He hops closer. I can feel sharp claws on my chest. He doesn’t dig his talons in, though. He just gingerly walks across my tattered blanket until his one good eye is looking back and forth between mine.

“I am concerned about the captain,” he says. “Concerned, concerned.”

“Why is that my problem?”

The navigator stirs in his sleep, and the parrot waits for him to be still, then leans closer to me. I can smell sunflower seeds on his breath.

“I am concerned that the captain doesn’t have your best interests at heart,” he whispers.

“Since when do

you

care about my best interests?”

“Behind the scenes, behind the scenes, I have been your greatest advocate behind the scenes. Why do you think you are in the captain’s inner circle? Why do you think you weren’t chained to

the diving bell when it went down?”

“Because of you?”

“Let’s just say I have influence.”

I don’t know whether to believe the bird, but I’m willing to entertain the idea that maybe he’s not the enemy. Or at least not the

worst

enemy.

“Why are you telling me this?” I ask.

“There may be a need to . . .” Then he begins bobbing his head nervously, so that his face makes figure eights in front of me.

“Need to what . . . ?”

He begins to pace on my chest. It tickles. “Nasty business, nasty business.” He calms down, is silent for a moment, then meets my left eye with his. “If the captain proves unworthy of the crew’s trust, I need to know I can count on you.”

“Count on me to do what?”

Then he puts his beak right up against my ear. “To kill him, of course.”

You lie on your bed. Shirt off. A feverless fever burns through your brain. Rain falls outside like the end of the world.

“Bad,” you mumble. “Something bad. Something bad will happen at school because I’m not there.”

Your mom rubs your back like she did when you were little.

“And when you were there, something bad was happening at home.”

She doesn’t get it. “I was wrong about something happening at home,” you tell her, “but this time I’m right. I know. I just know.”

You turn your head to look at her. Her eyes are red. You want to tell yourself it’s not from crying. It’s from lack of sleep. She hasn’t slept. Neither has your dad. Neither have you. You haven’t slept for two days. Maybe three. They’re both missing work. They take turns tending to you. You want to be left alone, but you’re afraid to be left alone, but you’re afraid to not be left alone. They listen to you, but they don’t hear you, and the voices tell you that your parents are a part of the problem.

“They’re not really your parents, are they?”

the voices say.

“They’re impostors. Your real parents were eaten by a rhinoceros.”

You know that’s from

James and the Giant Peach

—a favorite book when you were little—but it’s all so muddled, and the voices are so persuasive, you don’t know what’s real and what’s not. You know the voices aren’t talking into your ears, but they’re not exactly in your head either. They seem to call to you from another place that you’ve accidentally tapped into, like a cell phone pulling in a conversation in some foreign language—yet somehow you understand it. They linger there on the edge of your consciousness like the things you hear just as you’re waking up, before the dream collapses under the crushing weight of the real world. But what if the dream doesn’t go away when you wake up? And what if you lose the ability to tell the difference?