Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

Chernobyl Strawberries (38 page)

A nurse wearing civilian clothes (the special corps of cancer troops) took me aside to a hospital room which was obviously meant to be more like home, furnished with a comfortable sofa, a vase of flowers and two boxes of tissues at the ready, a world away from the hard plastic chairs and linoleum in the corridor outside. It felt as unreal as an undertaker's office or a morning-TV studio. I sat on the sofa and took a tissue, and then froze. I couldn't quite decide whether to be brave or start sobbing on the nurse's shoulder. She had seen us all before: the jokers, the stiff-upper-lippers, the tragedians. I only had this one take. âI am sorry, Michelle. I don't seem to have any questions. I should really be going home now.' I stood up, walked towards the door, then turned back. âHow am I going to tell my parents?' I asked, as though I had broken the most important promise I'd ever given them.

I knew how I was going to tell or not tell Simon. He was waiting for the phone to ring: a wordless call would suffice. That morning, I asked him not to come with me to the hospital, just as I asked him to stay away from the maternity ward almost three years before to the day, when our son was born. This was not always an easy thing to do in a world which

assumed that his duty was to be by my side, but he didn't mind. He understood that I was made of different mettle. I faced both my demons and my gods alone.

I walked out of the hospital slowly. The sounds of the city were muffled and distant. The day seemed to have been created for bad news. I stared at the familiar bends of the river. I could walk like this for ever, but I was scared of returning home on my own. Finally I called Simon to ask him to meet me. His tall, familiar figure emerged from the mist of a dying February afternoon. âA widower,' I thought, almost as though I was checking the word out for size. We tried intermittently to say something, but it was difficult to know where to start. I kept apologizing. I felt that I had betrayed him too in some way, worse than ever before.

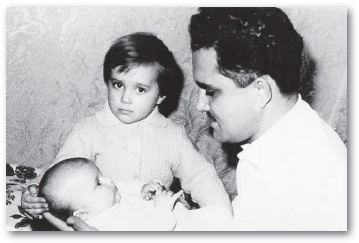

With my baby sister

I kept thinking that I was being punished for having it all so easy in the past. This was ridiculous, given that I believed in neither karmic destiny nor hubris, but how is a dialectical

materialist supposed to face terminal illness? My luck simply had to run out at some stage, I figured, and wished it had run out differently. I tried to be realistic. Even if it all ended tomorrow, no one except my mother could really say that I died young at forty-one.

I told myself I wasn't frightened, but I kept waking up at three a.m. drenched in sweat, staring death in the face. I thought about Alexander's future, and tried to be falsely generous towards Simon, thinking that he would remarry and forget, but I clearly wanted neither. I wanted to know for certain that he would spend the rest of his days sobbing at my grave and that no one would ever be able to replace me.

A week later it became much worse. One of the scans showed that the cancer had spread to my bones. We needed a repeat before we could be sure, but meanwhile the hospital vocabulary had changed, just in case. We talked about palliative care, maintenance, a positive attitude. No one mentioned

treatment

any longer. The grim reaper seemed to be sharpening his scythe. I kept being either cheerfully sarcastic or angry. I suspected that my positive attitude was somehow meant to make things easier for everyone else, and I rebelled in small, childish ways. One day, I was barely able to function at the thought of my own end, while the next I had become so accustomed to it that I was able to stop off and buy myself a sandwich at a riverside bar as I walked home from the hospital along the Thames. The river's tides were strangely comforting. âThe world will just go on without me,' I thought as I munched tuna on wholemeal bread and drank carrot juice, and contemplated the uselessness of my healthy eating habits. I had, self-evidently, not a single original thought about death.

Two weeks on and I gave up on the idea that I'd ever sleep past three a.m. again. Instead, I got up, put on my dressing gown and tried, pathetically, to get on with my academic writing. I was halfway through a book on travel when the world as I knew it ended. I had never noticed it before, but the newspapers were full of heroic examples of people who had climbed Everest in metastasis. Hitting the keyboard with my two index fingers seemed comparatively easy.

It wasn't going anywhere. I'd get up from my desk and walk to the bathroom and look at myself in the mirror, porcelain pale and poisoned. I stood on the tiles, feeling that I was like one of those shiny apples which you bite into, only to spit out brown, rotten flesh. I couldn't decide whether that was the legacy of my East European youth â all those factory chimneys belching black sulphurous smoke, all those coal fires â or of my Western European life â the plastic gloss on everything, invisible, equally poisoned. I needed to pin the blame somewhere. I needed to feel really angry. I couldn't.

One morning at four a.m., I gave up on my travel book and started writing a âlife-without-Vesna' manual for Simon. This was meant to be a practical little booklet, no tears, no deathbed speeches. He and I had â in the many years of living together â developed a system of duty-sharing, running the home in the fashion of German U-boat crews. No talk, no detectable traces. I did my work and he did his; what one knew the other need not worry about. I now set out to write down my portion of the U-boat duty rota. I listed my bank accounts and the bills I settled each month, my pitiful pension schemes and my savings funds: life's administrative debris. Then I wrote down how to set the video recorder and the washing machine, and how to programme each of a surprising number of timers around the

house. The more pointless the instructions seemed, the happier I felt writing them out.

My own choices seemed to funnel rapidly. I enjoyed the feeling of being in control, perhaps because control was the last thing I really had. Even the âlife manual' was getting out of hand. If it became longer than 3,000 words it would be as good as useless, the teacher in me worried. Then I realized that the reason I enjoyed writing it was the passwords to the past which I kept burying in the text. I was floating messages in a bottle which would mean nothing to anybody else except the two of us.

My son, on the other hand, was too young to have such shared memories. Only two at the time of my diagnosis, he would, in all likelihood, have difficulty remembering me in a couple of years' time. My photographs would erase my living face. The world I came from would seem as exotic and distant to him as accounts of nineteenth-century explorations of the source of the Nile. I was aware that although, since their late-Victorian heyday, his English ancestors kept moving into smaller and smaller dwellings, much of their history was still around. It was all there for Alexander to touch and see: the paintings, commissions signed by Victoria and George, letters of love and business, and pieces of uniform and dress.

His Serbian blood was, by comparison, like an underground river. The drifts of Balkan life meant that we kept little in writing, and sold or lost most that was of value from the past. We started afresh at regular intervals and owned barely anything that was older than us. I distilled everything further when I came to England: down to four suitcases, of which two were filled with books. I was so uninterested in material possessions that joining a family where everything was already in place was a blessing. The thought of decorating and furnishing a house â the kind of thing my mother loved â bored me. I was

happy simply to move in. Now I wanted to write myself into the picture in a way which surprised me. I was trying to capture my voice for Alexander so that he could hear it if and when he wanted to. His Serbian was poor and that was my fault, for I had always spoken English to him. Now my English â such as it was â would have to serve a sacred duty. I put the âlife manual' to one side and began to write my life for Alexander.

A week later, the second scan showed that the cancer was still

in situ

and hadn't spread. Everyone was talking about treatment again. It would be removed, counter-poisoned with the finest pharmaceuticals, you will sail through. Fear not, girl. Overwhelmingly â 76 per cent, according to statistics â the chances are that you will still be around five years from now. You are so strong, it is probably more than 76 anyway. I no longer really cared. I was, of course, glad to hear the good news, but my happiness had, in the meantime, ceased to depend on scan results. The illness had articulated the odds which everyone faced sooner or later. âWhy me?' somehow translated into âWhy not?' For whatever reason, I simply didn't fear death any more.