Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul (14 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

I’ll bet,

I thought to myself. In reality, it was a nursing home. Being called by another name didn’t erase my dismal image about such places. I wasn’t eager to “step down” to that type of nursing. However, I felt I owed the recruiter the courtesy of at least touring the place she’d offered.

A young woman from the office took me to the third floor. She explained that the residents were waiting to go to the dining room for their noon meal. I was appalled by what I saw. The hallway seemed endless and dark as a train tunnel. Wheelchairs containing the harnessed flesh of old people lined the walls. Heads bobbed, arms flailed and legs hung limply or kicked at random. Foreign sounds filled the air: grunts, groans, mutters, mumbles, sniffles and sobs.

Dejected faces stared into space. Pairs of eyes filled with loneliness followed us as we walked down the corridor. My tour guide cheerfully greeted each resident. Most responded with a timid smile. I was overwhelmed.

T

rue teaching is only achieved by example.

Plato

Reprinted by permission of Benita Epstein.

N

o tempting form of error is without some

latent charm derived from truth.

Sir Arthur Keith

As a part of the discharge teaching, the newly diagnosed diabetic patient was taught how to give his own insulin. The nurse who had been giving him the injections during his hospital stay instructed him on preparing the insulin syringe, then gave him the equipment and an orange to use to practice the technique. She also instructed him about diet, activity and monitoring his blood sugar, as well as what to do if his blood sugar was too high or too low. He had no questions when he was discharged and said he felt confident in administering his own insulin.

At his next doctor’s appointment, his blood sugar was very high. The doctor asked him if he took his insulin every day as instructed and if he followed his prescribed diet. The patient said he knew, from the diet teaching he received from the nurse in the hospital, that the juice of the orange was important in controlling his blood sugar. Then he proudly described his insulin administration technique: He drew up the insulin, injected it into an orange every morning and ate the orange.

Johanna Tracy

“That’s not the sliding scale I ordered!”

© 1998 Carl L. Shrader. Reprinted with permission of

Medlaff.com

.

H

e who laughs, lasts.

Norwegian Proverb

From the time I was four years old, I announced to anyone who asked, “When I grow up, I’m going to be a nurse.” My parents tried to nurture this dream. They would surprise me with little nurse’s kits. Contained in a small plastic case latched at the top was all the equipment needed to be a nurse: a thermometer permanently marked to 98.6, a pill bottle filled with candy (which would be gone in two hours), a stethoscope that didn’t work and, best of all, a syringe.

I loved that syringe. I would spend hours filling it up with water and “injecting” my little sister. I would “inject” the family dog and a very reluctant cat. No other single function represented nursing to me as well as giving injections. To me, giving shots was the epitome of what nurses do.

You can imagine my excitement, therefore, when we reached the part of my nurses’ training where we learned injections. I studied the techniques carefully and practiced on peaches. I practiced so much that the fruit at my house had little water blisters all over that looked like scabies. I participated in the “return demonstration” with my fellow nursing students. I always claimed that my partner’s injection was painless so that she would make a similar claim when it was my turn.

The following week, I began my emergency room rotation at Penrose Hospital in Colorado Springs. One day, a handsome, tanned construction worker was admitted with a large laceration on his right arm. About six feet, five inches tall, 250 pounds, he had huge muscles and a grin to match. “I just sliced this a little with some sheet metal, Ma’am,” he reported. He lay on the exam table while the doctor sutured him with a dozen stitches. He listened intently while the doctor gave instructions for wound care.

And then the magical moment occurred. The doctor turned to me and said, “Nurse Bartlein, would you please give this gentleman a tetanus shot?”

My big chance!

A real injection on a real patient. I practically floated on air as I scrambled to the refrigerator and took out the tetanus vaccine. I carefully drew up the prescribed amount and returned to the patient. I meticulously swabbed the site with an alcohol wipe and then expertly darted that needle deep into the deltoid muscle. I aspirated as taught and slowly injected the vaccine.

With a grin, the construction worker said, “Thank you, Ma’am” and stood up. I winked at him, and he winked at me. He stood there for a minute and promptly crumpled to the floor unconscious.

Oh, my God, I killed him! My first

injection and I killed the patient.

My impulse was to run out the door as far into the mountains as possible.

Forget about

being a nurse, forget about injections, I’ll live off the land. No one

will ever find me.

Everyone else came running and slowly helped the patient to his feet. The doctor could see that I was quite shaken. He reassured me with a smile and said, “Don’t worry, he’s fine. The big ones always faint!”

Barbara Bartlein

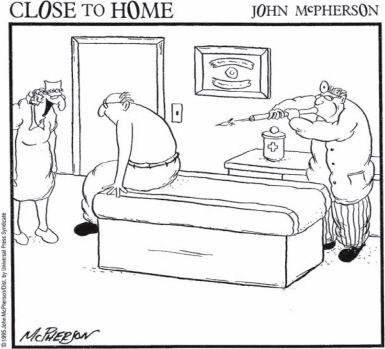

“Dr. Bigford is trying out a new inoculation method he found out about when he was traveling in Borneo.”

CLOSE TO HOME

© John McPherson. Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL PRESS

SYNDICATE. All rights reserved.

H

appiness is a warm puppy.

Charles M. Schulz

I was a new graduate nurse, on probation in my first job, when I met Mrs. Oldman, a charming lady of about eighty who’d never been ill or in a hospital.

One day, I saw her staring outside with tears in her eyes.

“Are you in pain?” I asked.

She looked up, startled, and shook her head. Smiling, she apologized. “No, I’m just silly. I’m lonesome for Peppy. I must be getting senile to cry for a little dog, but he’s always around me at home. I forget he’s not human. I talk so much to him, and somehow he gives me the impression that he understands me.” She wiped her eyes and looked helplessly up at me. “Do you think I’m silly?”

“Not at all,” I assured her.

“I’d do anything if I could see and hold him for a moment.” She questioned me with her eyes. Reading the hopelessness in my response, she said tonelessly, “No, I guess it’s impossible.”

“Some people are allergic to dogs,” I tried to explain, visualizing a dozen dogs, cats and heaven-knows-what other pets chasing each other under the beds during visiting hours.

She nodded sadly. “Of course.”

After that crying spell, she favored me with stories about Peppy. Her neighbor, Mrs. Freund, was taking care of him and claimed he knew she’d been in the hospital. Wasn’t that smart? Then she said sadly, “Yes, Peppy, he misses me. I miss him.”

She grew despondent as the days passed. I tried everything to draw her out and cheer her, but to no avail. Even the other ladies in the ward noticed my efforts and Mrs. Oldman’s silence. They offered snacks, refreshments and suggested they play cards with her. She thanked them gratefully, but her eyes had that lost expression and she politely refused everything. Patients came and went every day, and soon Mrs. Oldman was an old-timer, and one who’d grown dear to me. I’d often been told that a person could die if he or she lost the will to live. I feared Mrs. Oldman would give up and die if I didn’t find something to give her life meaning, a reason to live. It was then I thought of Peppy. Taking my camera, I went to Mrs. Freund’s house to take a picture of him. Surely that would cheer her.

Peppy sat demurely as he was photographed. No doubt the little, black, fuzzy fellow had once been lively in his youth, but now he sat with his head on his paws staring out into nowhere.

“Poor guy,” Mrs. Freund said, “he is so lonesome he could die. He hardly eats or drinks. He sits and stares out the window and whines softly for her.” She looked at me beseechingly. “It would help them both if he could visit Mrs. Oldman.” I shook my head. Mrs. Freund tried again. “How about just taking him to the courtyard so she can see him from her window?”

“Let’s try it,” I said enthusiastically. “Come between three and four tomorrow. All the head nurses will be at a meeting and I’ll be in charge.”

I told her to put Peppy in a shopping bag to pass the attendants at the entrance. Mrs. Freund was delighted. “Aren’t we glad she doesn’t own a Great Dane or a St. Bernard?”

The next day I could hardly wait for Mrs. Green to leave for the meeting. Visitors ambled into the ward. Everyone had company but Mrs. Oldman.

“Want me to pull your curtains around your bed so you have some privacy?” I suggested, knowing how she felt about the pitying stares from visitors.

“Yes,” she muttered.

I closed the curtain, wondering if our plan would succeed and if Mrs. Freund would manage to keep Peppy quiet in her bag while passing by the two attendants at the main entrance. I had not dared to tell Mrs. Oldman of our plan, fearing it might fail.