Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul (20 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

Marilynn Carlson Webber

F

aith evermore looks upward and decrees

objects remote; but reason can discover things

only near, and sees nothing that is above her.

Francis Quarles

I heard his footsteps before I saw him. In his brand-new Christmas slippers, his shuffling feet never left the floor. As I watched him traverse the hall, I had a sudden image of the little engine that could. His gray jogging suit, a recent birthday present, bagged about his tiny frame and a thatch of snow-white hair crowned his head. He looked awfully sleepy and needed a shave—not unusual for 3:00 A.M.

He approached the nurses’ desk and asked, “What are they gonna do with that pony?”

Thoughtlessly, I answered, “What pony?”

He ignored my question and began telling me they should put him down at the far end of the meadow and let him eat the yellowed cornstalks left from this year’s crop.

I smiled a sad smile and tried to re-orient John as to his whereabouts. Although pointless, I had a small glimmer of hope that I could make a difference, that I could make John see the reality of the nursing home. So I continued to patiently explain to John that he lived here in room 114.

Finally, I stopped, and as I gazed into his cloudy blue eyes, I suddenly recognized how much better his reality was than mine. He was in a meadow with a new pony. I was trying to place him within the stark walls of an institution.

I patted John on the shoulder, “I think that the far end of the meadow would be perfect for the pony.”

He continued shuffling down the hall, smiling.

Mary Jane Holman

W

ith the fearful strain that is on me night and

day, if I did not laugh, I should die.

Abraham Lincoln

Sadie was eighty-seven years old and had been in the hospital for two weeks when I met her. Though she was recovering quite nicely from a heart attack, she was also experiencing some dementia. She was always pleasant and smiling and called me “Honey child” when she spoke and told wonderful stories from the past. We spent hours together with her talking and me listening. A master storyteller, she disguised her voice to mimic the characters she so lovingly recalled. Her explicit facial expressions always added flavor to her tales.

Sadie’s dementia wasn’t apparent until she’d ask questions about the recent past or couldn’t find her way back to bed from the restroom. On a few occasions, she attempted to crawl into bed with one of her four roommates, causing uproar and much confusion. Sadie became sullen and quiet following these episodes, and I often wondered what she was thinking.

One morning I started my rounds as usual and noticed Sadie was very sad. She seemed to want to tell me something, but had difficulty finding the right words. After a few minutes I ascertained that she had had an “accident” during the night and needed a good bath and a manicure. I spent much of my morning soaking her hands in warm, sudsy water. To ease her embarrassment, I suggested she imagine she was spending the day being pampered at the beauty shop. We laughed together and played along until it came time to do her peri-care. As I soaked her bottom, she became very quiet again and her eyes grew as wide as saucers. I asked if I was making her uncomfortable in any way. She looked up at me and very innocently said, “Honey child, they’ve never done this to me at my beauty shop before!”

I bit my lip and told her I certainly hoped not, and then gently reminded her she was still in the hospital. We both laughed until we cried. And laughter was just the medicine Sadie needed that morning to regain her dignity.

Andrea Watson

T

he only good luck many great men ever had

was being born with ability and determination

to overcome bad luck.

Channing Pollock

The truth is, we were whining about being tired, and it was cold and dark as we ran to the helicopter at 0400 that morning. We had no clue this would be one of those flights we’d never forget.

After liftoff, dispatch told us to rendezvous with local EMS at the scene “of a gunshot wound to the neck.” Thoughts of being cold and tired were replaced by waving red flags. First, our EMS is a skilled and sophisticated service that only requests our presence at unusual events. Second is the consideration of the structures of the neck. A bullet in the cervical spine is frightening; a bullet through the trachea more frightening; a bullet through the carotid artery or jugular vein most frightening. Is the patient paralyzed? In need of a surgical airway? Spurting arterial blood? Is there an internal bleed occluding the airway? And where is the weapon? More importantly, who has that weapon?

We landed in the street of a neighborhood made up of small older homes. After egress from the aircraft, we approached the scene, noticing it did not have the feel of a catastrophic event. Law officers had the weapon secured. Our patient was under a huge tree on a front lawn. EMS had fully immobilized him and established two large-bore IVs. The heart monitor showed a normal sinus rhythm, and EMS reported stable vital signs. The victim was talking a mile a minute, which afforded us instantaneous information regarding level of consciousness and integrity of the airway. Assessment by flashlight revealed no paralysis. In fact, he was gesturing wildly to the extent that someone is able to do when he or she is fully immobilized. Cajoling him to stop talking long enough to peer into his oral cavity was the most difficult part of the assessment. There was no bleeding in his mouth. It was noted his top dentures were missing, which was his only complaint.

Overall, Lucky, as we came to call him, appeared to be quite healthy and spry for a gentleman eighty-nine years of age. He had no allergies, took no medications, and hadn’t the foggiest idea when he had his last tetanus booster. As we prepared to transport him, he pleaded with the EMS and law enforcement personnel to search for the missing dentures because the “gol-dang uppers had cost him an arm and a leg.”

During the ten-minute flight to the trauma center, Lucky remained in a sinus rhythm with stable vital signs. No symptoms were manifest and certainly shortness of breath was not an issue, as he animatedly relayed his story. A strange noise awoke him while his dog slept next to his bed. “The gol-dang dog never woke up and barked like a watchdog should.” Lucky grabbed the .22-caliber pistol he kept on his nightstand and charged into the night. Running out the front door, across the porch, and into the yard, he tripped over an exposed tree root. As he fell, the pistol fired, striking him in the neck. During the melee, he lost his uppers. The gol-dang uppers had cost him an arm and a leg—which remained his chief complaint.

In the emergency department, examination under bright lights revealed an entrance wound in the neck, an abrasion to the hard palate, and a small laceration without active bleeding at the base of the tongue. To everyone’s amazement, X rays of the head and neck showed no bullet fragments.

News of such a mysterious event always travels fast. There was already a crowd of “night people” forming in the emergency department when EMS and law officers from the scene arrived, bearing the missing uppers. There was complete silence as the multitude gaped at the sight of the dentures with the .22-caliber slug imbedded into the hard palate portion.

After completing our paperwork, we usually say goodbye and good luck to our patients before departing for base. It seemed prudent to dispense with the good luck part of our salutation to Lucky. Our last impression of him was of a little old man under a heap of blankets with a shock of unintentionally spiked hair (hence the term, hair-raising experience!) sticking from the top of the blankets. Sticking out the other end were his little house slippers that appeared to be older than he was.

As we left the department we could hear Lucky telling no one in particular, those gol-dang uppers had cost him an arm and a leg—the best investment Lucky ever made!

Charlene Vance

I

nvention is the talent of youth as judgment is

of age.

Jonathan Swift

After years of hospital nursing, I loved my new job in a busy family-practice office, performing a wide variety of duties—phlebotomy, spirometries, EKGs. I accepted each as a new challenge and mastered all of them with confidence.

Well, almost all of them.

I was still nervous whenever I cut off a cast. To prove to the patients (and to me!) that the motorized saw wouldn’t cut their flesh, I always put my fingertip next to the spinning circular blade. I then explained how the cotton padding underneath the cast snagged the blade and stopped it before it reached the skin. But, in spite of my own reassurances, cutting casts still made me a bit nervous— especially when the patient was a squirming four-year-old boy.

Danny had broken his arm in a playground accident a few weeks earlier, and I had assisted the doctor in applying his cast. When I rewarded his bravery with double trinkets from the toy chest, Danny and I became buddies. He had complete confidence in my ability to remove his cast.

That made one of us.

With a reassuring smile I fired up the cast-cutter and started cutting the cast, hoping he’d think the trembling was from the vibration of the saw, not my hands.

The motor buzzed and bits of plaster flew as I methodically pressed the whirling blade back and forth along the length of the cast. Danny started to fidget in the chair, and his face flushed.

“Doing okay, Danny?” I asked.

“I’m okay.” He smiled meekly. “It don’t hurt.” But his facial expression and wiggling told me something was making him uncomfortable.

Thankfully, just then, the final part of the cast was cut. I carefully pried it apart with the cast spreader. After showing him the blunt-ended scissors and promising him they couldn’t cut his skin either, I began cutting the cotton padding and underlying stockinet. Danny wiggled some more and even winced a bit when I spread the cast further and gently lifted his arm out of the cast.

I gasped to see a long purple streak on his inner arm! My mind raced for a diagnosis. Phlebitis? Necrosis? Had I cut him? There was no blood!

There, inside the opened cast, embedded in the padding, was wedged a purple crayon.

Bewildered, I looked at Danny.

He said, sheepishly, “It itched!”

LeAnn Thieman

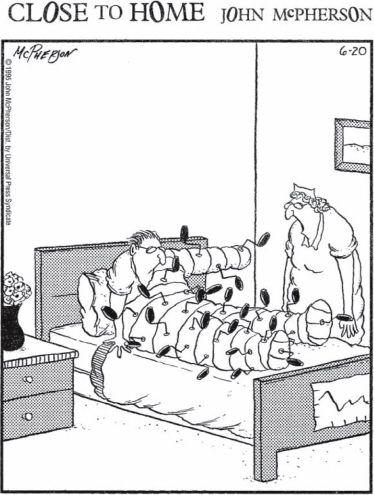

“If you get an itch, just turn whichever one of these cranks is closest to it.”

CLOSE TO HOME

© John McPherson. Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL PRESS

SYNDICATE. All rights reserved.

I

am only one; but still I am one. I cannot do

everything; but still I can do something. And

because I cannot do everything, I will not refuse

to do the something that I can do.