Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul (3 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

And mostly to God, for his divine guidance.

How many times over our years of working with patients have we exclaimed, “I could write a book!” Well, now, together, we have. Nearly three thousand health caregivers from all over the world shared their stories—their hearts, their souls. While we at

Chicken Soup

have been compiling stories for three years, they have been a lifetime in the making. Now your book,

Chicken Soup for the Nurse’s Soul,

shares the love, the challenges and the joys of being a nurse.

Most of us didn’t choose this career because of the great hours, pay and working conditions! This book reminds us why we did. Stories from students help us recall why we entered this profession in the first place. Stories from seasoned nurses reveal why we stay. Some stories reflect on the “good old days” (many of which didn’t seem all that good at the time!), but all of them give us hope for the future.

Regardless of our ages or areas of practice, all of us in health care will find our own hearts and souls in these pages. We’ll see the universality of what we do—the power of our skillful hands and devoted hearts.

These stories, like nursing, celebrate life and death. Read them one at a time, savoring the hope, the healing, the happiness they offer. We envision this book in every break room (or bathroom—some days they’re the same thing!). Or after a long, hectic day (or night!), we recommend a prescription of a little “Chicken Soup,” prn, ad lib.

We honor you for your ministry to humankind and offer this book as our gift to you. It is our sincere wish that

Chicken Soup

for the Nurse’s Soul

gives back to you a portion of the love and caring you’ve given to others. We hope it inspires you to continue your compassionate service. The world needs you.

The Florence

Nightingale Pledge

I solemnly pledge myself before God and in the presence of this assembly to pass my life in purity and to practice my profession faithfully.

I will abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous and will not take or knowingly administer any harmful drug.

I will do all in my power to maintain and elevate the standard of my profession and will hold in confidence all personal matters committed to my keeping and all family affairs coming to my knowledge in the practice of my calling.

With loyalty will I endeavor to aid the physician in his work and devote myself to the welfare of those committed to my care.

We would love to hear your reactions to the stories in this book. Please let us know what your favorite stories were and how they affected you.

We also invite you to send us stories you would like to see published in future editions of

Chicken Soup for the Soul.

Please send submissions to:

Chicken Soup for the Soul

P.O. Box 30880

Santa Barbara, CA 93130

fax: 805-563-2945

You can also visit or access e-mail at the

Chicken Soup for the

Soul

sites at

www.chickensoup.com

and

www.clubchickensoup.com

.

We hope you enjoy reading this book as much as we enjoyed compiling, editing and writing it.

M

any persons have the wrong idea about

what constitutes true happiness. It is not

attained through self-gratification but

through fidelity to a worthy purpose.

Helen Keller

Reprinted by permission of © Hallmark Licensing, Inc.

I

f a man loves the labor of his trade, apart from

any questions of success or fame, the gods have

called him.

Robert Louis Stevenson

It was an unusually quiet day in the emergency room on December twenty-fifth. Quiet, that is, except for the nurses who were standing around the nurses’ station grumbling about having to work Christmas Day.

I was triage nurse that day and had just been out to the waiting room to clean up. Since there were no patients waiting to be seen at the time, I came back to the nurses’ station for a cup of hot cider from the crockpot someone had brought in for Christmas. Just then an admitting clerk came back and told me I had five patients waiting to be evaluated.

I whined, “Five, how did I get five? I was just out there and no one was in the waiting room.”

“Well, there are five signed in.” So I went straight out and called the first name. Five bodies showed up at my triage desk, a pale petite woman and four small children in somewhat rumpled clothing.

“Are you all sick?” I asked suspiciously.

“Yes,” she said weakly and lowered her head.

“Okay,” I replied, unconvinced, “who’s first?” One by one they sat down, and I asked the usual preliminary questions. When it came to descriptions of their presenting problems, things got a little vague. Two of the children had headaches, but the headaches weren’t accompanied by the normal body language of holding the head or trying to keep it still or squinting or grimacing. Two children had earaches, but only one could tell me which ear was affected. The mother complained of a cough but seemed to work to produce it.

Something was wrong with the picture. Our hospital policy, however, was not to turn away any patient, so we would see them. When I explained to the mother that it might be a little while before a doctor saw her because, even though the waiting room was empty, ambulances had brought in several, more critical patients, in the back, she responded, “Take your time; it’s warm in here.” She turned and, with a smile, guided her brood into the waiting room.

On a hunch (call it nursing judgment), I checked the chart after the admitting clerk had finished registering the family. No address—they were homeless. The waiting room was warm.

I looked out at the family huddled by the Christmas tree. The littlest one was pointing at the television and exclaiming something to her mother. The oldest one was looking at her reflection in an ornament on the Christmas tree.

I went back to the nurses’ station and mentioned we had a homeless family in the waiting room—a mother and four children between four and ten years of age. The nurses, grumbling about working Christmas, turned to compassion for a family just trying to get warm on Christmas. The team went into action, much as we do when there’s a medical emergency. But this one was a Christmas emergency.

We were all offered a free meal in the hospital cafeteria on Christmas Day, so we claimed that meal and prepared a banquet for our Christmas guests.

We needed presents. We put together oranges and apples in a basket one of our vendors had brought the department for Christmas. We made little goodie bags of stickers we borrowed from the X-ray department, candy that one of the doctors had brought the nurses, crayons the hospital had from a recent coloring contest, nurse bear buttons the hospital had given the nurses at annual training day and little fuzzy bears that nurses clipped onto their stethoscopes. We also found a mug, a package of powdered cocoa and a few other odds and ends. We pulled ribbon and wrapping paper and bells off the department’s decorations that we had all contributed to. As seriously as we met the physical needs of the patients that came to us that day, our team worked to meet the needs, and exceed the expectations, of a family who just wanted to be warm on Christmas Day.

We took turns joining the Christmas party in the waiting room. Each nurse took his or her lunch break with the family, choosing to spend his or her “off-duty” time with these people whose laughter and delightful chatter became quite contagious.

When it was my turn, I sat with them at the little banquet table we had created in the waiting room. We talked for a while about dreams. The four children were telling me about what they wanted to be when they grow up. The six-year-old started the conversation. “I want to be a nurse and help people,” she declared.

After the four children had shared their dreams, I looked at the mom. She smiled and said, “I just want my family to be safe, warm and content—just like they are right now.”

The “party” lasted most of the shift, before we were able to locate a shelter that would take the family in on Christmas Day. The mother had asked that their charts be pulled, so these patients were not seen that day in the emergency department. But they were treated.

As they walked to the door to leave, the four-year-old came running back, gave me a hug and whispered, “Thanks for being our angels today.” As she ran back to join her family, they all waved one more time before the door closed. I turned around slowly to get back to work, a little embarrassed for the tears in my eyes. There stood a group of my coworkers, one with a box of tissues, which she passed around to each nurse who worked a Christmas Day she will never forget.

Victoria Schlintz

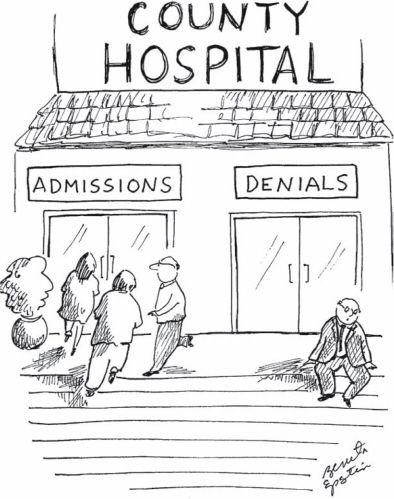

Reprinted by permission of Benita Epstein.

H

ow wonderful it is that nobody need wait a

single moment before starting to improve the

world.

Anne Frank

I just saw another television show where the nurse was portrayed as an overly sexed bimbo. It’s obvious the image of the nursing profession still needs some good public relations. Once in a while, we have an unexpected opportunity to educate the public to what nursing is all about.

My chance came on a warm Saturday morning when I had a coveted weekend off from my job in a long-term care facility. My husband and I headed for the Cubs ballpark via the train. Just as the train arrived at the final station, the conductor curtly shouted for all the passengers to immediately leave the car. He hustled us toward the door. On the way, I glimpsed some people huddled around a man lying limply in his seat.

The conductor talked excitedly into his walkie-talkie. I heard fragments of “emergency” and “ambulance.” Surprising myself, I approached him and said, “I’m a nurse. Could I be of any help?”

“I don’t need a nurse,” he rudely snapped back, loud enough for the crowd to hear. “I need a medic!”