Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs (6 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

Stacey Flood

Stacey Flood

received her B.A. in English from DePaul University in 2003. She lives in Chicago with her boyfriend and their three dogs. She is currently attending culinary school, and she loves to cook for her friends and family. T.J. continues to learn new things every day with the help of his extraordinary speech therapists, and he and his dad are still “partners in crime.” The two of them have developed a new passion—anytime you ask T.J. where he wants to go, all he will say is “Monster trucks.” Contact Stacey at [email protected].

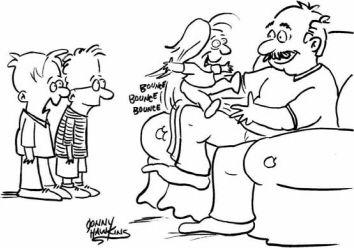

“My sister has special needs—

and my dad has special knees.”

Reprinted by permission of Jonny Hawkins. ©2007 Jonny Hawkins.

F

orget past mistakes. Forget failures. Forget everything except what you’re going to do now and do it.

William Durant

After years of doctors, counselors, and visits to the school, the word “bipolar” should have been a relief. My thirteen-year-old son had always been different and unusual, but the problems had escalated. Even if it was my fault, as one doctor told me, our family and my son needed help, and we weren’t getting it. Not until now. The words hung in the air, and I swear I could touch them— they were so heavy and dense.

Josh sat with my husband and me as the doctor told us what bipolar disorder is, described the symptoms, and outlined the line of treatment that was needed. But all I remember hearing were two words—bipolar disorder.

After our meeting, my son and husband were picking up some literature and filling out paperwork, so I offered to go warm up the car. There was snow on the ground. I remember feeling like my whole life was in a frozen picture. I couldn’t think; I couldn’t breathe; I couldn’t cry. I was numb.

At that very moment, my husband and son jumped into the car, and I remember looking into the rearview mirror and seeing my son grinning from ear to ear. He jumped into the seat and said, “Mom, let’s go celebrate.”

At that very moment, I knew that my son was in the middle of what the doctor had described as a “manic episode.”

Why else would he say something so ludicrous?

As calmly as I could, I turned to him and said, “Son, I’d love to go celebrate, but what exactly are we celebrating?”

And with the most sincere voice I have ever heard, he looked me in the eye and said, “Don’t you get it, Mom? We’re celebrating because I am sick. I’m not evil.”

It was in that moment that I realized it was time for me to start seeing things the way my son did. I thought we had been striving for normality, but all along he had been fighting for his soul.

Deborah Rose

Deborah Rose

is a private investigator, spending her free time advocating for people with mental illness. She is heavily involved with the NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) Texas as an educator and stigma buster. Deborah enjoys reading, writing, debating, and eBaying. Full-time writing is next on her agenda. Joshua is now a twenty-two-year-old college graduate with a degree in business management and marketing, working as a case manager for the Salvation Army while working toward his master’s degree in business. He is also working on a documentary that focuses on the shared problems of teens and young adults, whether they have mental illness or not. Please e-mail Deborah at [email protected].

The Voice of Reason Wears

SpongeBob Underpants

I

n the book of life, the answers are not in the back.

Charlie Brown

“Oh, my child will never behave like that in public,” I remember smugly telling a friend over lunch one day. “I simply won’t allow it.” Seven months pregnant with my first baby, I watched in horror as a preschool-aged girl screamed, kicked, and flailed while her humiliated mother tried to drag her away from the play area and out the door.

“I tell you, I’ll never let a three-year-old run my life!” I smirked as we got back to our discussion of nursery themes.

Looking back, I seemed to have all the answers regarding child rearing before I ever had one of my own: when and what they should eat, the proper cartoons to watch, which toys they should be playing with, the best way to potty-train. If it concerned children, this expectant mother had an opinion about all the “right” ways to do things, and shame on anyone who disagreed!

So sure was I that badly behaved children were the direct result of bad parenting that nothing short of a whack over the head could have convinced me otherwise. And, as karma would have it, that whack occurred late one night in June 2003 in the form of a four-pound, nine-ounce screeching baby boy.

Difficult from the beginning, little Antoine was determined to put our fledgling parenting skills to the test. I was committed to nursing him, but he refused to latch on. Gastrointestinal problems meant that the milk I spent so much time pumping almost always came back up. He screamed, sometimes for hours on end, for no apparent reason. He stared, not at us, but at a bright light on the ceiling. And the child never

ever

slept, which meant, of course, that neither did we.

As time went on, his behavior became even more challenging, and sometime around his first birthday we stopped taking him to public places altogether unless we simply had no other choice. His unpredictability and his “nuclear meltdowns” in the supermarket, for example, more often than not had me terrified that one of my fellow shoppers would summon the police.

Gone were the days of enjoying restaurant meals as a family, as even a fast-food experience with Antoine was likely to deteriorate into a chaotic scene. In fact, a trip outside our home for any reason typically meant enduring finger-pointing, cold stares, and rude comments from perfect strangers as Antoine, oblivious to his surroundings, carried on as though he were being prodded with hot pokers.

“Can’t you control your child?” “Ma’am, if he doesn’t quiet down, I’m going to have to ask you to leave,” “Spoiled brat,” or “Give him to me for a few days, I’ll straighten him out!” came my way so often that I began to categorize my days by the number of insults I received from people who knew absolutely nothing about me or my child.

Worst of all was the “advice” we received from friends and family whenever we attempted to voice our concerns that something wasn’t quite right with our little boy. Some tried to reassure us, claiming that perhaps the “terrible twos” had set in a bit early, that tantrums were

normal,

and that he’d settle down once he got older. “He’s just all boy,” some said. Others gently pointed out that he would behave better if we could simply learn to show him “who’s boss,” while still others were competitive: “Oh, you think he’s bad, you should see my Brian.”

How on Earth could we possibly explain what it was like to live with this whirling dervish, this Tasmanian devil of a boy to people who clearly thought that children came in a one-size-fits-all model? And who was to say that they weren’t right? As first-time parents, what did we know? After all, no one had ever told us that raising kids was easy.

What we did know was that the level of stress in our household (already at an incomprehensible high from trying to meet the day-to-day needs of a child who alternated between ramming his head into the armoire and spending hours at a time lining his toy cars into neat little rows) was made even higher by the large amount of seemingly thoughtless commentary we received, no matter which way we turned. Indeed, it was commentary of the very type I had made myself once upon a time.

When Antoine’s diagnosis of autism was eventually confirmed, we—like most parents confronted with the disorder—were devastated. At the same time, the sense of relief was profound. Knowing that there was a reason behind our child’s erratic behavior and that we weren’t crazy after all gave us the strength to go on when it seemed like our whole world was falling apart.

These days, Antoine has more good days than bad. At three and a half, he is the light of my life and has taught me more about myself than I could have imagined possible. He still does not make transitions well, and, though fewer and farther between, his meltdowns can still be considered “nuclear” by anyone’s standards. That much has not changed.

What has changed is my own ability to empathize, to put myself into the shoes of another. Never again will I be so quick to make judgments. These days, thanks to knowing and loving my amazing little boy, if I say anything at all, it is this: How can I help?

Shari Youngblood

Shari Youngblood

received her B.A. in cultural anthropology and M.A. in sociology from the University of Florida. Proceeds from her ASD-centered merchandise (

www.cafepress.com/madwhirl

) go toward autism research, and her forthcoming book,

Imbecile,

concerns raising an autistic child in France. Currently, Antoine can usually be found keeping his mother in line, as happened recently at the local supermarket. Upon sensing that Shari wanted to ram a rude customer’s shopping cart with her own, a slow shaking of Antoine’s head and a solemn “No, Mama” nipped her recalcitrant behavior in the bud. E-mail her at shari.young [email protected].

“I feel a tantrum coming on.

You better start thinking up some excuses for it.”

Reprinted by permission of Jean Sorensen and Cartoon Resources. ©2005 Cartoon Resources.

O

ur lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

See the little girl, who stands out most

and has troubles following suit,

who forgets a lot, and talks out of turn

and to others doesn’t seem very cute.

“She’s disruptive” . . . “Doesn’t listen,”

“Shouldn’t be with all the rest,”

You see it . . . we hear it,

“She holds your son back from his best.”

We see your looks of disapproval

through eyes that have never seen,

the struggles that we face each day,

the place where she has been.

We hear you talk . . . those things you say,

though you fail to really listen,

to the voice whose words seem disregarded

“Our star,” who to us, does glisten.