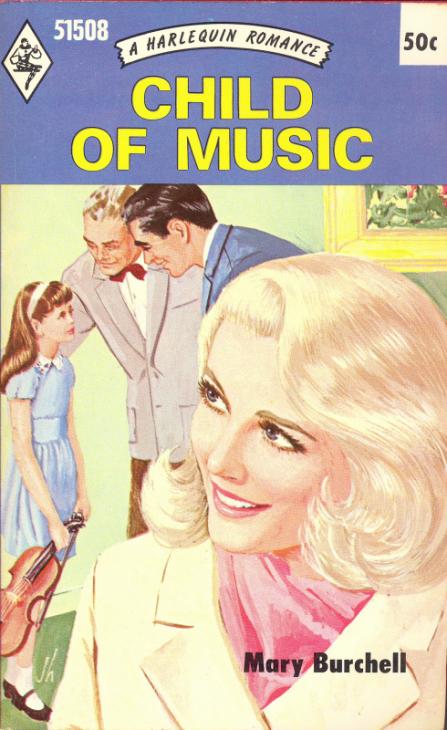

Child Of Music

Authors: Mary Burchell

CHILD OF MUSIC

First

published in 1970 by Mills & Boon Limited,

17 - 19 Foley Street, London, England

SEN 373-01508-9

Harlequin Canadian edition published July, 1971

Harlequin U.S. edition published October, 1971

All the characters in this book have no existence outside the imagination

of

the Author, and have no relation whatsoever to anyone bearing the

same

name or names. They are not even distantly inspired by any individual known or unknown to the Author, and all the incidents are pure invention.

The

Harlequin

trade mark, consisting of the word HARLEQUIN and the portrayal of a Harlequin, is registered in the United States Patent Office and in the Canada Trade Marks Office. CLS

Copyright, © , 1970 by Mary

Burchell

.

All rights reserved.

Printed in Canada

Mary Elliott

entered the staff room at Carmalton Girls' School; flung down a pile of books and, as she went to help herself to the rather weak coffee provided, exclaimed resignedly,

'Does anyone share my view that Janet Morton isn't really quite all there?'

Miss Curtis, always ready to take umbrage, even about so undistinguished a member of her class as Janet Morton, bristled slightly. 'It depends what you mean by "not quite all there". She's a dreamy child, of course.'

'Dreamy! She's in a trance half the time.' Mary Elliott laughed exasperatedly, for teaching

maths

to resistant juniors is no fun. 'I'd got them all more or less busy this morning when I saw her gazing out of the window, obviously a hundred miles away. And when I asked her to

favour

us with her thoughts—'

'You shouldn't do that,' interjected Miss Curtis. 'Sarcasm withers children.'

'It didn't wither Janet Morton. She came back from her hundred-mile journey and said, "I was thinking about the wind." '

'The

wind

? Oh, dear!' Miss Sharpe, longest on the staff and with an effortless sense of discipline which was the envy of all, laughed outright. 'She was just showing off.'

'But she wasn't,' sighed Mary Elliott crossly. 'If she had been I could have dealt with her. I think she really

had

been thinking about the wind, and how one does that I just wouldn't know. I told her to get on with her work, of course, and she did. But when

Ï

looked at it afterwards it was all wrong, and I felt somehow defeated.'

'When you've been at it ten years you won't mind so much,' Miss Sharpe told her consolingly.

'When I've been at it ten years I'll be certifiable if many of them are like Janet Morton,' retorted Mary Elliott, as the door opened again to admit her special friend Felicity Grainger.

'Who's talking about Janet Morton?' Felicity wanted to know.

'All of us. Which is a bad sign. No child is sufficiently important to command general attention,' declared Miss Sharpe.

'Not even if she's a near-genius?' Felicity inspected the coffee and grimaced, while Mary Elliott said,

'Oh, Felicity, really! Just because the child scrapes that violin of hers effectively!'

'What makes you think Janet Morton a near-genius?' inquired Miss Sharpe with genuine curiosity.

'In some odd way, she's the most truly musical person — and I mean person, not just child — that I've ever come across.' Felicity frowned

consideringly

. 'It's not only that she has a technique and a capacity for sheer hard work outstanding in a child of eleven. There's a sort of inner knowledge — an instinctive awareness and artistic judgment which almost frighten me at times.'

'Then we'll leave the subject,' Miss Sharpe declared amusedly. 'The day those brats begin to frighten one it's time to take them less seriously.'

Everyone laughed feelingly at that, and the subject was dropped. But later, in the kitchen of the pleasant cottage which Mary Elliott and Felicity Grainger shared, Mary paused over the joint preparations of their evening meal and said impulsively,

'Do you really think the Morton child so out of the ordinary, musically speaking? It isn't just that you're sorry about her being an orphan and romantically inclined to exaggerate her gifts?'

'Heavens, no!' Felicity laughed. 'Naturally I'm sorry for any child robbed of both parents in the same ghastly accident. Who wouldn't be? But I wouldn't judge her gifts sentimentally because of that. Anyway, I think she's quite happy in her foster-home with the Emlyns. Mrs. Emlyn is kind and homely and hasn't read any books on child psychology. She just gives Janet the sort of simple day-to-day security which is what she most needed after such a shock.'

'Maybe you're right.' Mary nodded thoughtfully. 'But I shouldn't have thought the Emlyn household conducive to artistic development, would you?'

'No, it isn't. But security and normality were what Janet needed most. She's allowed to practise as much as she likes without being thought either wonderful or tiresome, which is important. I don't think anyone has ever told her she's unusual, for the simple reason that the Emlyns don't even know that she is. That must have been very healthy for her! But now, of course—'

Felicity paused and into her beautiful grey eyes came a determined gleam which Mary had seen there once or twice before when her friend was about to

display

unusual obstinacy.

'Now,' Felicity went on firmly, 'it's time Janet was found a place in a school specially geared to the training of musically gifted children. In fact — the

Tarkman

Fou

ndation

School.'

'I thought perhaps we were coming to that,' Mary looked both curious and amused. 'They say the competition is pretty ferocious, and that only one in a hundred gets in.'

'I know. But, unless I'm much mistaken, Janet Morton

is

that one in a hundred,' replied Felicity, setting her mouth.

It occurred to Mary to say that Felicity could very well be mistaken, but she rejected the idea. For when Felicity looked like that Mary knew by now that argument was pointless.

On the surface the two friends had little in common, Mary being quick, volatile, impatient and superficially a trifle hard, while Felicity was quieter, artistic and something of a dreamer. But, in fact, of the two Felicity was the one who could stand foursquare for the few things she regarded as important.

They had come to

Carmalton

in the same term just over a year ago and, as neither wanted to live in lodgings, inevitably they converged on the same charming cottage which was the only one to be rented in the district. They met literally on the doorstep, concealed with difficulty their dislike of each other as rivals and then, on discovering that the rent was considerably more than either had anticipated, simultaneously hit on the idea of sharing it, at least for an experimental three months.

'It would be a risk, of course,' Mary said. 'We may loathe each other within a week. But, on the principle that half a loaf is better than no bread, how about trying it?'

'I'm willing,' Felicity agreed. 'But I should warn you that in my job as music teacher I'm bound to do a certain amount of

practising

, both piano and violin.'

'Are you any good?' inquired Mary candidly.

'I am rather.'

'Then I'll risk it. If

I

find it insupportable I'll tell you so and we'll have to come to some oilier arrangement."

But she found it far from insupportable. She even said sometimes that she quite enjoyed it. And on her side, Felicity, who had been an only child, found Mary Elliott's companionship both stimulating and pleasant.

Both were reasonably domesticated without being obsessively so and, with the twice weekly assistance of an invaluable Mrs. Arnold, they shared the household chores amicably. That particular evening, Felicity was, in her own phrase, knocking up a meat pie while Mary peeled vegetables — and presently came round once more to the subject of Janet Morton.